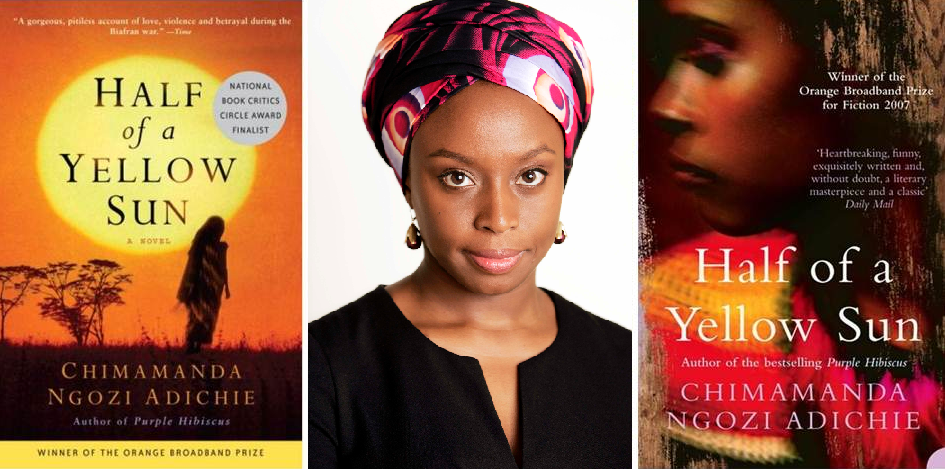

Half of A Yellow Sun is the title of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel and also the symbol the Biafran armies donned on their sleeves during their late 1960s struggle to cede from Nigeria and establish an independent republic, Biafra, in southeastern Nigeria.

The struggle is not without grief, hardship, and sacrifice. As two factions wage in war, psychological tolls accompany the physical battles for power and ownership over contested territories.

Adichie has a way of drawing readers in for the first portion of the novel that has us less focused on the story at hand, and more on the characters, their personalities, and their interrelations. The experiences of the gruesome realities of war stem from the perspective of a few Igbos.

We enter the lives of a houseboy named Ugwu; his master Odenigbo, a professor with revolutionary dreams; his lover Olanna who also works at the University; her twin sister Kainene who is a stalwart businesswoman; and her lover Richard, a white Englishman with a zeal for Nigerian culture. We get to know them before we are suddenly dropped into the maladies of war and feel a deeper connection to their trials and triumph behind enemy lines.

The vicissitudes of war are ever apparent.

In the beginning, there is hope and excitement. An aura of verve surrounds the promise of victory. The energy is charged with upbeat speeches from the Igbo group’s fearless leader, who they fondly call His Excellency.

Soon, however, the quotidian realities of the war settle in. The inhumanity of it.

In the novel, it becomes clear how the meanings and impacts of war differ based upon one’s proximity to the violence. Neighbors find themselves across enemy lines, due to their membership in different ethnic groups.

Some only experience a snippet of the war. One man talks nothing of hunger, malnutrition, and displacement, only of his improved polo game.

The implications are that the aftermath of war will leave a vastly different imprint on the memories of those who lived through it and how those memories will be passed on through generations.

For some ethnic groups, war is at most a fragment of minutes on the nightly radio broadcasts, but for the most part, their daily lives undergo no major disturbance.

Others come to know the war by its most intimate moments and gruesome details: heads ripped off in jagged cuts by shrapnel; young mothers-to-be raped, their babies torn prematurely from their wombs; houses lost through occupation, and only recovered if bought anew at steep prices.

For these Igbo people, the Biafran struggle is a story passed down from fathers to sons and from mothers to daughters. This narrative of strife remains an important, though plaintive, time in the history of the ethnic group.

Children also do not escape the horrors of war.

Young children fall ill with starvation or kwashiorkor, the swelling of small bellies pulling their stomachs taut. Most haven’t enjoyed meat in years but have out of necessity grown fond of the smell of fried crickets, lizards, and rats.

Old children become soldiers overnight through mandatory conscription.

Families are unexpectedly torn apart when loved ones who venture outside on a brief errand, never return.

The mind is left to dangle all of these thoughts, all unfortunate and out of one’s control.

Eventually, the weakened side grows weary of revival speeches as each successive city is captured, fear spreads widely, and the impending reality sets in that the end of the war might only come at the end life and not at the celebration of victory–a frightening, if not sobering, consideration.

As the discomfort and deaths wear on, the costs of warfare seem steep, and after the fighting stops and the dust has settled, we are left wondering whether the end justified the means.

Adichie thankfully does not fill the story with loads of her own propaganda and leaves it up to the reader to weigh the merits of war–its motivations, benefits, and drawbacks.

Both sides are content to see the war end. Civilians are relieved to reclaim their livelihoods. In one instance, low-ranking soldiers also seemed delighted to shed the face of brute intimidation for one of neighborly kinship.

This is a dear reminder to readers that although inhumane acts were committed by both Nigerian soldiers and Biafrans who bore the half of a yellow sun, the war was fought between humans.

Adichie acknowledges that cruelties abound in times of war, but in the case of Africa and Africans, the brutalities do not detract from the humanity of the people, who have graced the earth from immemorial times and who through this day strive in Ma’at for harmony and peace.

This is a wonderful review of Half of Yellow Sun. I have read that book and I entreat everyone to go for it. Adichie is a writer. No doubt.

The new kid on the block in Nigeria is obviously Ms. Chimamanda Adichie. Here writing is spotless. Thanks for sharing this one with us Nefetiti. I am buying that book soon.

Understanding Nigeria during those times of war in Biafra is certainly difficult. But Adichie provides something so profound here. I enjoyed reading that book and this review of course.

There was a movie made about this book. Half of a Yellow Sun (2013) 111 min. A Drama Romance film that came out on 16 May 2014 (USA) with a 5.9 rating on IMDB. Of course that is no mark of the book itself. This book was inspiring to say the least.

Film gist: Sisters Olanna and Kainene return home to 1960s Nigeria, where they soon diverge on different paths. As civil war breaks out, political events loom larger than their differences as they join the fight to establish an independent republic.

Director:

Biyi Bandele

Writers:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (novel),

Biyi Bandele (screenplay)

Stars:

Chiwetel Ejiofor,

Thandie Newton,

Anika Noni Rose

Great book! That’s all that should be said.

I loved reading this book, Half of a Yellow Sun, great book. Great writer. Wonderful, just wonderful.

Chimamanda Adichie is one of the greatest writers I have read. And Half of a Yellow Sun does not disappoint.

With Americanah and Half of A Yellow Sun I think this lady is legit. While the war for Biafra’s independence, born out

of highly complex Nigerian and international political circumstances, provides the essential context for the novel, Adichie’s focus is on the

personal and private, the struggle of the civilian Igbo population. Her

depiction of the horrors of war, the starvation and destruction is

realistic.