School

The strange man comes with something we already have—our skills, knowledge, training, and expertise—and says he will give us just that if we attend his schools. And we go, most of us do, though reluctantly, at first.

With the next generation, we long forget our reluctance. We are no longer pushed, against the will of our fathers and grandfathers, to attend school. Rather we anxiously await the very moment we can follow in our older sisters and brothers and cousins’ footsteps. We proudly wear an empty, oversized backpack upon our small shoulders, hoping to fill it with something substantive and weighty.

School brings us hope for a future as bright as it is unknown, for what exactly we are supposed to get out of school, is an enigma still. Our parents say go to school. Listen to the teacher. Learn. And something magical will happen. If only you can recite your multiplication tables, your periodic tables frontwards and backwards, row after row, with your eyes closed, in your deepest of sleep, you will make it.

What precisely will you make and where will you make it? Know that if you ask too many questions, it is not the illogic that is nonsensical—no, you are the troublemaker. Just as you can become the driver of your own success, you can equally become the architect of your own demise.

Nonetheless, there still remains no clear answer to how school works and what a student is to get out of it, besides knowledge that you would have acquired anyhow—what person schooled or unschooled has not learned that one and one equals two—or knowledge that is useless and would have changed nothing had you never known it—how many people have encountered molten lava and needed to measure its temperature? How often does someone cruise on the highway at sixty-five miles per hour and need to know how fast a train should travel to reach the same destination at a quicker pace?

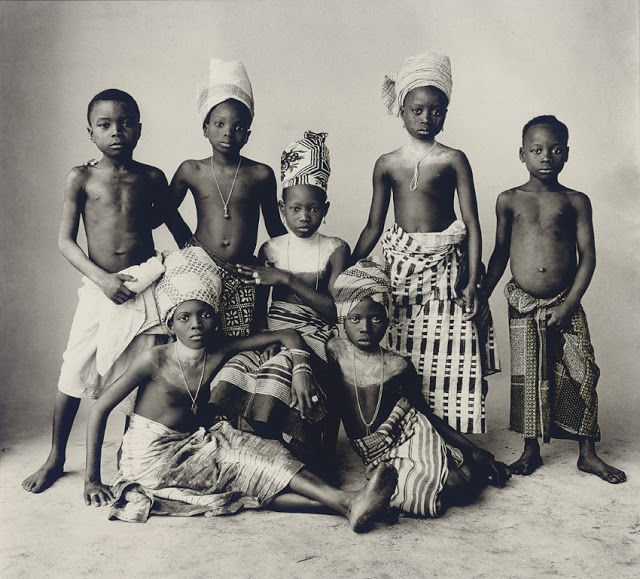

There could actually be a useful curriculum in school, if it were not designed by people who are paid to try their darnedest to make it useless. Most students, even, do not mind meandering through decades of futility, so long as they stand a chance to blossom from one of those small boys to a big man. As a small boy, he enters school and in those hallowed halls of learning, he disappears—trailing off into the sunset only to reappear five or ten or twenty years later with that “made it” look and “made it” car and “made it” story building, to boot. The grin on his face and the enamored looks surrounding him give off that consumption and the power to consume conspicuous materials goods is an integral component of making it.

Just one generation after we were pulled out of our villages, we lunge out to school on our own accord. No strong current, no fishing lure, or no crafty persuasion necessary. School also leaves no promises to enrich our communities, only our materials appetites. School promises us what we already had—our skills, knowledge, training, and expertise—and leaves us with less. We are in no better position to operate our family farms, distilleries, trades, and businesses having spent our formative years away from the farm, distillery, trade, and business. School has in fact distanced us from our international expertise and brought us in closer proximity with the outsider and his motives than to our own grandfathers and grandmothers.

There is nothing traditional about modern schools which form cleavages between our communities, our villages, and ourselves. There is nothing that schools teach us that we cannot acquire through other means. Yet, the physical separation of school from our families is its crowning achievement. Its psychological separation is not far behind, as it convinces us that we have more to learn from a strange man from a faraway town who writes in a strange language than we have to learn from the people residing in our own village. School convinces our parents of the same, and in no time, we are all looking elsewhere for guidance on how to care for our communities and ourselves.

Though if we look around, we do not have to look far to realize that the strange man is only teaching us through his school, which we willingly attend, how to care for his family and himself and how to neglect our own environments. But still we pack our bags hoping that his classes will contain the answers to our conundrum—a problem that, unbeknownst to us, is not on the exam.

Absolutely right

Instead of the kind of schooling system and curriculum we have, we should have one that really speaks to us and about us

We must learn our own history and write our own curriculum. Thank you Amara please keep the articles coming, keep teaching!

… METHA-stacised and no longer at ease in the African dispensation, we have become ensnared in our economic, social and cultural oppressions. We can’t breathe!!!