ATLANTA, Georgia, USA – The United States of America must now begin to revisit one of its many federal laws that has for years persecuted African Americans, in fact, just about any group of black people living in that country. This is the federal law that made the possession of marijuana a crime since the 1930s.

The origins of this legislation is firmly rooted in American racism. It was also to some extent directed towards darker skinned Mexican immigrants who were associated with marijuana use at the time. This racially loaded history lives on in current federal policy, which is so driven by the myth of white superiority and the propaganda of eschewing only whiteness as virtue.

The logic is impervious to reason. The cannabis plant, hemp or weed, was widely used in the United States for fabric during the mid-19th century. Smoking weed is documented to have appeared on the Texas border towns around 1900, brought by Mexican immigrants who cultivated cannabis as both an intoxicant and for medicinal purposes before they arrived in the US.

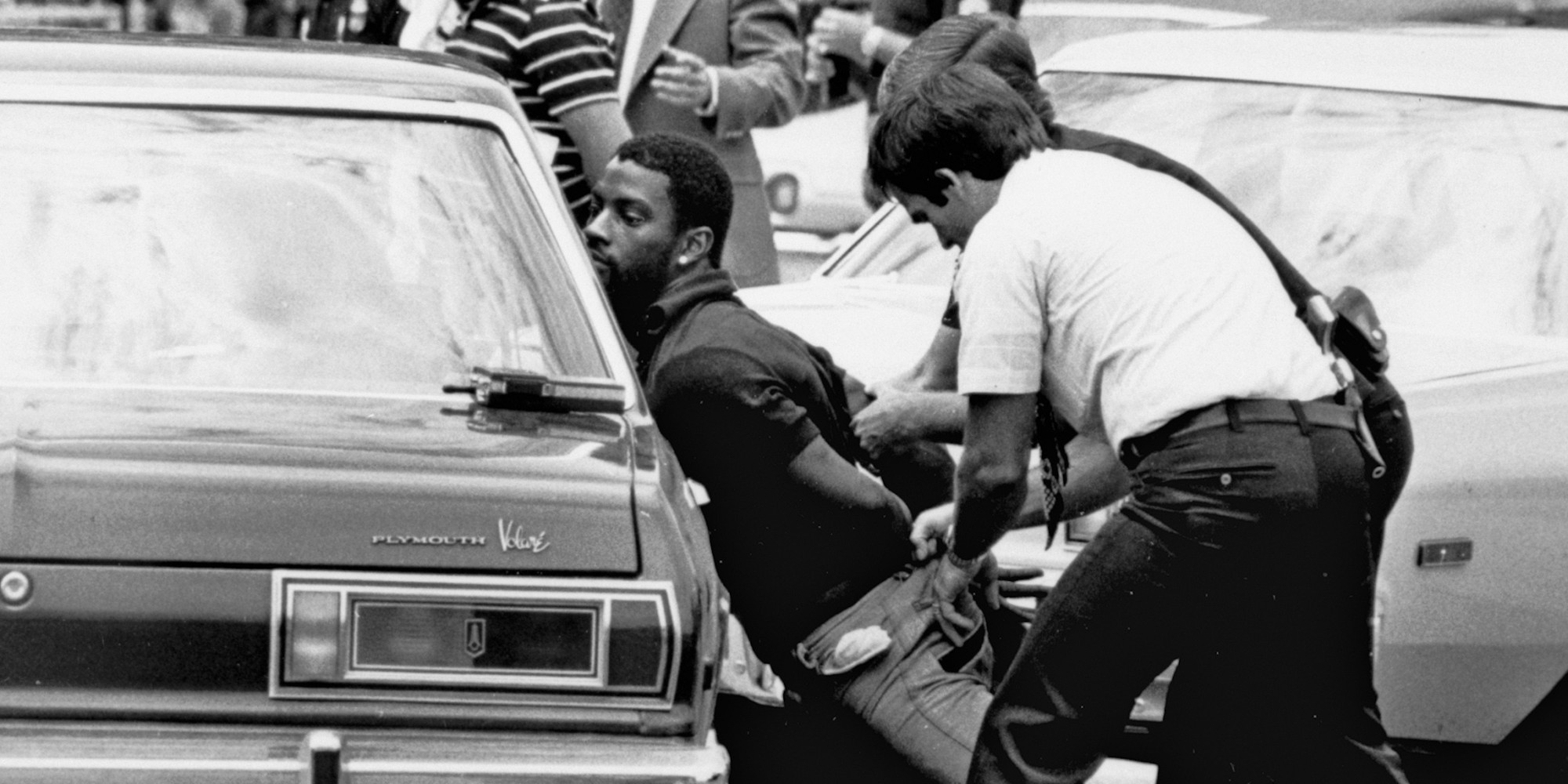

US Law Enforcement of the marijuana crime was indelibly shaped by the fact that Black people used it too. Hence in a frightening but assured attempt by racist institutions, enforcing the arrest of Black people associated with Marijuana use became the end goal and a solution in terms to be achieved in curling America’s Black problem.

However, the propaganda machine tuned its discourse towards painting a ludicrous assertion that hemp use was only initially connected to brown people from Mexico, Black people and people from poor communities. And that police brutality against Blacks and brown Mexicans was incidental.

In that explanation, the propaganda machine invariably exercised even far reaching implications of whiteness. Black people were not only demonized as addicts because they were not disciplined enough to resit the psychoactive ingredients in weed, but they were perhaps defined even more so as not genetically fit to withstand the harmful use of the drug. In effect, they were not as human as white people.

Hence the Police in Texas border towns demonized everyone black and the plant also became bedeviled in these racial terms as the drug of “immoral” or “unfit” populations – Black people – who were promptly labeled “fiends.”

The legal scholars Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread explain in their authoritative history, “The Marihuana Conviction,” the drug was popular among minorities and other groups. This was not true. Most research conducted by the Derveoni Reserach Insitute indicate that hemp was equally popular, if not more, in white only communities.

Practically the attachment of the bedeviled weed to Black people ensured that it would be classified as a “narcotic,” attributed with addictive qualities it did not have, and set alongside far more dangerous drugs like heroin and morphine, so that African Americans can be amassed into the American prison system.

What was the motivation besides racism?

By the early 1930s, more than 30 states had prohibited the use of marijuana for nonmedical purposes. The federal push was yet to come.

The stage for federal suppression of marijuana was set in New Orleans, where a prominent doctor blamed “muggle-heads” — as pot smokers were called — for an outbreak of robberies. The city was awash in sensationalistic newspaper articles that depicted pushers hovering by the schoolhouse door turning children into “addicts.”

These stories popularized spurious notions about the drug that lingered for decades. Law enforcement officials, too, trafficked in the “assassin” theory, under in which killers were said to have smoked cannabis to ready themselves for murder and mayhem.

All this in tandem sensationalized white attitudes towards African Americans.

In 1930, Congress consolidated the drug control effort in the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, led by the endlessly resourceful commissioner, Harry Jacob Anslinger, who became the architect of national prohibition. His case rested on two fantastical assertions: that the drug caused insanity; that it pushed people toward horrendous acts of criminality. Others at the time argued that it was fiercely addictive.

He actually believed his propaganda, and he fed it to the public by giving lurid stories to the press as a way of making a case for federal intervention. This narrative had a great effect at Congressional hearings that led to the enactment of The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which in a guise to eradicate the use and sale of the drug through heavy taxation, actually enforced the mass incarceration of African Americans.

Mr. Bonnie and Mr. Whitebread report that the witness list for those hearings contained not a single person who had done significant research into the effects of cannabis. Mr. Anslinger testified that even a single marijuana cigarette could induce a “homicidal mania,” prompting people to want to kill those they loved. The bill passed handily; President Franklin Roosevelt signed it into law.

It was not until 1951, when Congress again took up the issue, that a reputable researcher was called to testify. Dr. Harris Isbell, director of research at the Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Ky., disputed the insanity, crime and addiction theories, telling Congress that “smoking marijuana has no unpleasant aftereffects, no dependence is developed on the drug, and the practice can easily be stopped at any time.”

Despite Dr. Isbell’s testimony, Congress ratcheted up penalties on users who were overwhelmingly Black. The states followed the federal example; Louisiana, for instance, created sentences ranging from five to 99 years, without parole or probation, for sale, possession or administration of narcotic drugs.

The rationale was not that mairjuana itself was addictive — that argument was suddenly relinquished — but that it was a “steppingstone” to heroin addiction. This passed largely without comment at the time since America’s prisons had begun to fill with Black people who were once again like under Slavery used as objects of free labor.

The United States of America accepted a senselessly punitive approach to sentencing Black people as long as it kept them in prison and supplied America’s Free Market system with adequate free and forced labor.

But, by the late 1960s when information technology had begun to take off, the knowledge that white college students from the middle and upper classes used marijuana, smoked weed, and doped hemp as well had begun to circulate with speed.

Seeing a few white lives ruined by marijuana laws, white public attitudes which was hitherto inane and nonchalant to the plights of black communities begun to alter, mainly about harsh sentencing, and, in 1972, the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse released a report challenging the approach of the US federal government.

The commission concluded that criminalization was “too harsh a tool to apply to personal possession even in the effort to discourage use,” and that “the actual and potential harm of use of the drug is not great enough to justify intrusion by the criminal law into private behavior, a step which our society takes only with the greatest reluctance.”

The Nixon administration however dismissed these ideas. Again because, the clandestine plan to seek and destroy Black men, Black families and hence Black communities was on course. In addition, the lobbyist started calling for the privatization of the prison system itself, calling the public institution inefficient, in order to maximize profits and consequently speed up the rate of the mass incarceration of Black men and the adequate supply of free labor to the free American markets.

During the mid-1970s, virtually all states some-what softened penalties for marijuana possession. Thirty-five states and the District of Columbia have made medical use of some form of the drug legal. But this medical use was almost always and only available to white Americans. Black communities continued to suffer the devastating effects of the mass incarceration and disenfranchisement of able-bodied Black men.

The Justice Department’s recent decision not to sue states that legalize marijuana — as long as they have strong enforcement rules — eases the tension between state and federal laws only slightly, and only in favor of white Americans who can get doctors to prescribe the hemp, but leaves a great many legal problems unresolved regarding the unlawful and immoral devastation of Black lives and black communities.

The US federal government has taken a baby step back from irrational enforcement. But it is reluctant to take the bold step, the moral conviction and the human approach back in putting the stop to America’s institutional racism and its mass incarceration of Black people.

The Supreme Court of the USA clings to a policy that has its origins rooted strongly in racism and xenophobia, against Black lives, and whose principal aim and effect has been to ruin the lives of generations of Black people for absolutely no particular reason but for the myth of ‘whiteness’ and to make the most money for its industrial capitalists!