[I]nspired by Alex Kotlowitz’s New York Times Magazine article, The Interrupters immerses us into the tumultuous and at times surreal world of a few inner-city Chicago neighborhoods. A world where ‘twelve and thirteen year olds are walking around with bullet proof vests under their clothes’ and where ‘every time I come outside somebody is getting killed.’ It’s a world where the majority survive by hustling. But as Violence Interrupter Ameena Matthews points out ‘hustle [can only] get you in one or two places.’

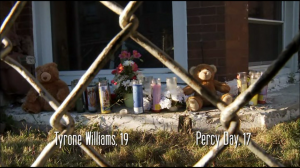

Her words ring true, as throughout the film we’re reminded of premature deaths. Teddy bears, half-burnt candles, and half-empty liquor bottles mark the last living locations of victims of violence. Those who escape death cycle in and out of jails, and an unprecedented 80 percent of Chicago’s black men have jail records.

This homicide epidemic has plagued the inner-city Chicago community for many years, ripping apart families and futures. Yet, people living in the community are frustrated with the overall lack of effort to end the violence.

Chicago’s 80 percent of black men who go to jail contribute to the cheap slave labor force that enables capitalism to thrive. In fact, many goods that are ‘made in America’ should be stamped ‘made in America’s prisons.’

All able-bodied federal prisoners are required to work, yet on average, they only earn 93 cents per day for their labor, with the lowest wages being a measly 16 cents per day. Compare this to the lowest minimum wages of 5.15 dollars per hour, and it becomes evident that private organizations have no incentive to stop the violence that would increase their cheap labor source.

The media also lack incentive to stop the violence. News cameras roll through every community march and town speech, with tape recorders poised at just the right angle to capture the voices of the community. But coverage of Chicago’s ‘war zone’ boosts ratings and ending the killings would mean that these news companies might lose viewers. The film shows the media as a fourth wall that is never broken, an invisible presence that has followed the violence from its inception but never intervenes to end it.

Violence Interrupters like Ameena Matthews, Cobe Williams, and Eddie Bocanegra resolve to take matters into their own hands. The documentary follows a year in their lives as they aim to stop killings and violence in Chicago’s inner-city communities like Englewood and Atgeld Gardens.

Started in 2004, the CeaseFire organization believes that the spread of violence mimics the spread of infectious diseases, and so the treatment should be similar: go after the most infected. Violence Interrupters aim to interrupt the transmission that turns grievance into violence, to channel people’s negative energy and built up anger and aggression in a direction that doesn’t result in lost lives.

Filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, 1994) does not disappoint in this documentary which is both moving and eye-opening. Rather than inserting himself into the narrative, he lets the subjects tell their story.

Violence Interrupter Ameena Matthews, the only female interrupter we come across, has one of the strongest voices in the film. She lays out the importance of women speaking out and getting involved in the movement against violence, which destroys the lives of their sons, brothers, and fathers. As a child, Ameena was an ex-gang enforcer herself and a ruthless one at that. She had a rep that extended beyond her father Jeff Fort, one of the biggest gang leaders in Chicago’s history.

Ameena sees a bit of her former self in a young girl named Caprysha, and spends much of her time being a friend and a mother-figure to Caprysha. Attempting to steer Caprysha to a path away from the street life, Ameena talks with her about her dreams of getting her high school diploma, going to college, and becoming a pediatrician. She takes Caprysha to get her nails done and her hair styled, experiences that Caprysha’s absent parents cannot provide. It’s these little things that we take for granted that give life meaning.

It’s too late for many of the adults who are already caught up in the prison/parole cycle, but Ameena looks to the future, to the children. That is her inspiration for being a Violence Interrupter.

She says: “I know if they had a strong person that lived that life, they can be saved.”