Close to 10 percent of the world’s cotton comes from Africa. Most of this cotton is then however taken to Asia for further manufacturing. Could Africa’s textile industry make a comeback?

Francois Traore grows cotton in Burkina Faso. He is one of 450,000 farmers from six African countries whose cotton runs under the label “Cotton made in Africa”, which wants to create better conditions for African farmers on the global market.

By joining the initiative, Traore agreed to refrain from using chemicals on his crops and to send his children to school. In exchange he receives training in modern agricultural methods, a financial advance for seeds and fertilizer and a slightly higher price for his cotton. Traore however still worries about his family’s future. “It’s a paradox. We send our children to school but later they won’t find any work,” says Traore. “Through the cotton we produce, we actually create work for people in other countries and these people then sell the manufactured goods back to us. That is why Africa is being destroyed.”

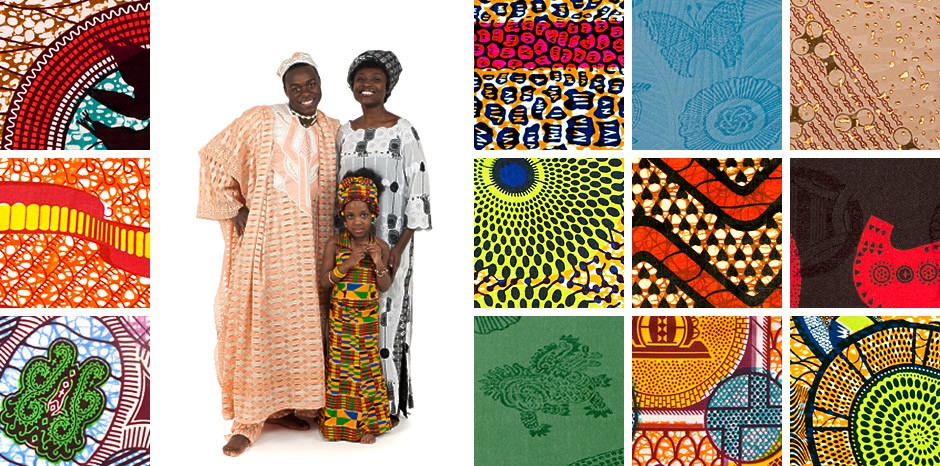

One major problem, is that Traore’s cotton only gains value once it is turned into threads, fabric and garments in China and other Asian countries. The Dutch label Vlisco, for instance, is the producer of colorful wax-print fabrics, which are in high demand in central and western Africa. Yet only one third of Vlisco’s fabrics are produced in Africa. “The reason why that percentage is not higher is that there is not enough supply,” explains Vlisco’s Director of Corporate Affairs, Jan van der Horst. “If more suppliers would pop up and produce the right quality, we could source 100 percent of our needs of cloth in Africa. But unfortunately, those suppliers are not there.”

The strength of the Asian market

In the 1980s, many African countries did have textile industries. These were however squeezed out of the market through competition from Asia.

“In Africa, the average spindle speed is about 10.000 rounds per minute. That same spindle in China is running at 20.000 rounds per minute. That means the Chinese or the Indian spindle is producing twice as much,” explains Jas Bedi, a Kenyan businessman who also sits on the board of the African Cotton and Textile Industries Federation (ACTIF). Moreover, explains Bedi, energy costs in Africa are almost twice as high as in China or India. When you calculate your costs and benefits, he says, “you are actually four times worse off: your cost is double and your production is half.”

Despite all the odds, Bedi believes in the future of Africa’s textile industry. China, for instance has seen a sharp rise in workers’ wages, which are far above African levels. Additionally, Africa’s population is on the rise. “In 2040, we’ll have 1.2 billion people of working age. That’s going to be bigger than India, bigger than China,” says Bedi. “If we don’t manage that labor pool, not only will Africa be unstable, the whole world will be unstable.”

Asian textile manufacturers are still at an advantage in terms of infrastructure and technology.

Textile firms with their eyes set on Africa

The first large textile firms are already showing interest in moving part of their production to Africa. The Swedish label H&M is for instance building a factory in Ethiopia. The US company PVH, which produces labels like Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger soon plans to start production in Kenya.

The Turkish garment manufacturer Ayka, which produces textiles for the German company Tschibo amongst others, has also opened a branch in Ethiopia, in which it has invested US$ 160 million (127 million Euro). It currently employs around 7,000 people and soon hopes to scale the number up to 10,000. Wages in Ethiopia are much lower than in China, says Kemal Öznoyan. He is in charge of Ayka’s overseas branches.

Öznoyan also admits that textile investors like Ayka, are still rare in Ethiopia and therefore enjoy a somewhat special status. “In Ethiopia, I have the Prime Minister’s direct telephone number. I have the numbers of all ministers,” he explains. “So when we have some problems, I have the correct numbers in my mobile and can ask about the cause. In Ethiopia, we are doing it that way.”

Ethiopia’s open arms practice towards its Turkish investors is however not a standard enjoyed by all who have their eyes set on Africa. Bettina Guemto is a German woman who has spent her last 15 years in Cameroon. Together with her now deceased husband, she started a small firm which prints company logos onto T-Shirts and employs 180 people.

Cameroon has clear regulations on what requirements companies have to fulfill, says Guemto. Yet she has regular visits from officials with armed guards, who threaten to close her business, alleging that she has unsettled bills to pay. It is corruption, she says and illegal in Cameroon and it all costs time and money to solve.

In the World Bank 2014 “Doing Business” report, it stated that African countries like Rwanda, Burundi and Ivory Coast had taken some of the best steps to ease business relations with investors. Yet while Africa is gearing itself up to get a stake in the textile industry, the continent still has many unresolved problems, like logistics, corruption as well as security issues to address.

The interviews for this report were conducted at the “Cotton mad in Africa” and “Competitive African Cotton Initiative” stakeholder conference in Cologne, Germany.

By Andreas Becker

The textile industry in West Africa is definitely a colorful and exciting one.

I love African clothing and textiles.