Animals and Humans: Is There a Difference?

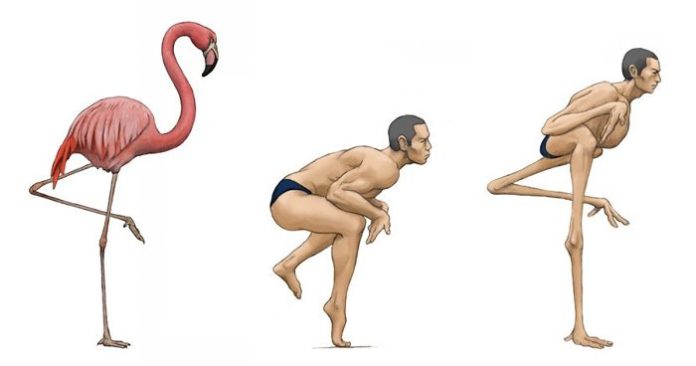

Is it simply a sign of human hubris to think we are much different from forest animals?

We eat, they eat. We sleep, they sleep. We procreate, they procreate. All by much the same means, measure, and pleasure.

Then what is so different?

Well, we humans can get diplomas from highfalutin colleges and universities. We can lose ourselves in careers imminently on the verge of some version of success. How different we must be.

Do forest animals read books? Do forest animals ramble about their hopes and dreams and aspirations or stockpile ample reserves for this life and the next? Do forest animals make five-year plans? Surely, they do not. Surely, they cannot.

How different we certainly are.

We have demonstrated that we can yearn for and achieve a daily diet that spans cultures and condiments. But surely a farm kitten cannot enjoy a jungle cat’s diet.

Surely a forest animal cannot mark several plots of land—one in the country, another by the sea, and still another in the mountains. But, yes, we humans can.

Adding to all these things we have set to distinguish ourselves from the farm animal, we further stress that this process of distinction, indeed the very act of thinking, is yet another characteristic of our ingenuity.

We humans perceive ourselves as thoughtful creatures, our minds ever crowded with choices and judgments. But truly thoughtful creatures, unlike humans, would often show careful consideration or attention to the needs of others, both fellow humans and forest animals. Certainly, thought is not solely a product of having a thinking brain.

Thinking, likewise, is not without its faults. Humans might imagine possible situations, remember or recall things to mind, decide on possible actions, or express particular opinions—whatever does this thinking have to do with making good, right, sound, or just decisions?

Thought or thinking alone are insufficient to make claims of superiority. Arriving at reason or logic is not a grand feat, as both only chart circuitous paths to self-defined destinations. What is reason but our own explanation or justification for our own actions? What is logic but our own effort to catapult ourselves above other beings?

But is this view of the world, of our worlds, as two—separate and unequal—is that a genuine reflection staring at us through the calm waves of a clear river or is that purely a reflection of our socially constructed, intelligently designed formal training?

In the halls of higher ed and lower ed, in our texts and in between the words of carefully typeset pages, we are socialized, and some might say indoctrinated, to understand our differences more than our similarities.

We are far better compensated to theorize and ponder about how we humans differ from our fellow living, breathing creatures. Though we receive no compensation to pursue knowledge towards how we could live together in mutual respect and harmony. We allow the rewards of compensation and those people who put compensation first, before all, to man the steering wheels that drive our societies.

This is how we differ from our ancestors. In this separation of human and animal, while both inhabitants of the same planet, we, unlike people who came before us, have made the conscious decision to be different.

Currently, our aim is to differentiate humanity from nature. Our philosophies are structured to forge the appearance of dissimilarity rather than unity, to invent chasms between ourselves and the natural world. With the ultimate desire that we can exercise some grand omnipotence over it.

In relentless pursuit of a mirage—a figment of happiness, achievement, desire, gluttony, and greed—we humans have diverged from other living, breathing beings in their appreciation of the real, seemingly mundane, pleasures of life.

We humans have abandoned waking up to a sun-kissed morning after a long night’s rainfall…for the fluorescent glow of a corded lamp. We humans have forsaken the sounds and smells of buzzing bees…for the acrid stench of bug repellants. We humans have cast aside the chill of a gentle breeze brushing against our naked skin… for the steady staleness of recycled air.

Is this life? Is this progress? Or do we have something, still, to learn from forest animals.

We have everything to learn from forest animals seeing how much the primitives from the west are killing the planet. We have everything to learn from forest animals because they are much better in thinking and in philosophy than the forced indoctrination of mass consumption and mass shitting that we continue to be force-fed by the Euro-American empire. The best thing that happened to this planet was a philosophy right from the cookbooks of Africa that nature has everything to teach us. And the worse thing that happened to this world is that the West became powerful enough to violently entrench their primitive ideas on the rest of the word.

But we are different from the other creatures. In essence we are all ultimately made up of bundles of energy called atoms but in terms of brain power we have no equal. We can ponder and grasp how the universe originated, works and how it might even end. That’s a powerful mind we have. Yes, we also create the most havoc, that’s true. But that’s comes with the territory. The most powerful being is also potentially the most destructive. That’s how nature works

Interesting… true. I wonder, what would you say to the ensuing idea that God is also the Devil.

Narmer Amenuti LOL I actually wrote that then deleted it as it may sound offensive to some. Yes of course, God is POTENTIALLY the biggest Devil there is. In fact it is exactly because of this that Ma’at came about. There has to be a body of laws to govern how we handle or power as humans hence Ma’at

Well, you know, I don’t shy away from the controversial. Lol.

In Vodun, there’s no devil. Only the Supreme Being, the Gods, the Ancestors, and the Spirits. The powers that be are in constant struggle between “good” and “evil”. Sometimes, what is good is evil to another. And so the balancing begins: and the rituals, the libation and the sacrifices all add to making sure that we, the first in contact with the rest of nature, adhere to Ma’at and begging the Gods to adhere to Ma’at and to help us also adhere to Ma’at.

In this way alone, I believe that the ancients in Africa were supreme thinkers. Their whole idea of Ma’at is one in which they have carefully understood that both humans and their Gods must all obey Ma’at if we are to live sustainably. Constant, unremitting violence against nature (or barbarism) then is not an excuse, since superior beings do not have excuses for barbarism.

In truth, if you look back to the beliefs of ancient Egypt and the ancient near east there was no devil external to man. God and devil were and are two potentialities in us as humans. The God of the Greek Philosophers also gave birth to the ‘spirit’ devil as well. It’s the Greeks who popularized such notions of God and devil.

Nice piece.