BAURU, Brazil – Brazil’s 7-1 defeat at the hands of Germany in Belo Horizonte took players, pundits and fans completely by surprise. In Mathematical speak, how do we put a figure on exactly how shocking the even was? This perhaps flawed attempt to quantify our astonishment at the Brazilians’ thrashing is a cautionary tale for mathematically inclined investors.

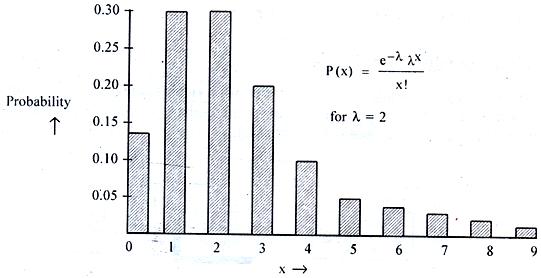

Let us, for pure edification, employ an incredibly simple model: it assumes that goals in football follow a “Poisson Distribution”. The Poisson is a statistical staple because it is broadly applicable in the real world: it calculates the chance of a given number of events (such as goals being scored) happening within a specified length of time (such as a 90-minute football match), given the average rate at which those events have occurred in the past.

The rate in this world cup is the average number of goals scored per team per match. In this tournament, after Germany’s shock victory, this was about 1.4 (or 2.8 goals per game), according to the FIFA World Cup records on Wikipedia.

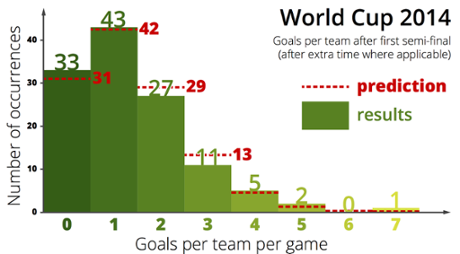

The Poisson distribution does an impressive job of describing the competition so far. The graph below shows how often teams scored a certain number of goals in a match. The bars show the actual results: teams scored zero 33 times, scored a single goal 43 times, and so on.

The total is 122, from the two teams in each of the 61 matches played up to and including the Germany-Brazil game. The dashed lines then show what the model predicts. It looks like a pretty good fit, but for one egregious exception: some team scored seven goals in a single match!

In fact, according to my model the odds of a team scoring seven or more goals in a match are well below 1 in a 1,000 games. So there you have it – a quantified surprise. Like the nation of Brazil, this must be equally shocking in the world of mathematics.

Even more surprising is the level at which this is happening. There are just 64 matches in a modern World Cup, and there have only been 800 matches in the competition’s entire history. This invites an almost philosophical question: how likely is it that, on that night, we genuinely witnessed a 1-in-1,000 game of football, unlikely to be repeated in a World Cup for perhaps a century hence? While it was quite a match, that seems an extraordinary claim.

The alternative is that the collapse of the Brazilian defence wasn’t a once-in-a-lifetime event. Perhaps this simple model doesn’t properly account for extreme events? It has done relatively well on the majority of matches, but a 7-1 thrashing does something fishy to the Poisson’s predictions.

There are myriad explanations, statistical and sporting, for Germany’s incredible seven-goal outlier. One likely contender is that football violates the assumptions implicit in this analysis. For example, the Poisson assumes that every goal is independent of every other goal: it assumes that the likelihood of scoring in any given minute of the match is the same, regardless of whether a single goal has been scored, or six. This seems implausible: Germany’s crowning three minutes, in which they went from 1-0 to 4-0 up in just 179 seconds, were surely not independent.

Perhaps an astounded Brazilian defence, gawping after Germany’s second rapid-fire goal, simply let the next two past? Or did the German team momentarily find and exploit their ruthlessly effective mojo? Whatever the explanation, it seems unlikely those goals were independent of one another.

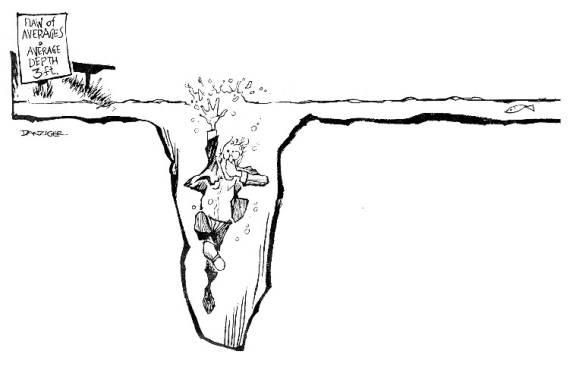

This is a common problem when using statistical models, and it comes up in another context where the stakes are often higher, especially in the global financial system. Traders frequently use equations and algorithms to determine whether to buy or sell. Often computers will follow mathematical models automatically, trading thousands of times per second – far too fast for human oversight.

These algorithms run into similar issues as seen here. For example, a financial model might assume that the prices of certain stocks, currencies or commodities are more independent than they really are. As the financial system becomes ever more complex and interconnected, this kind of assumption makes it increasingly likely that models will ignore the kinds of extreme events we saw in Belo Horizonte, or during the 2007 financial crisis.

It’s even plausible that naive application of mathematics can contribute to modern financial crises.

For example, the widely-used Black–Scholes equation notoriously only works under conditions where market movements are marginal. In the real world, large shifts in stocks happen more often than the model predicts. Since so many investors make use of Black–Scholes and related models, shocks can affect the whole market and contribute to systemic collapse.

Similarly, there have only been a handful of financial crises interspersed in decades of regular trading, which makes it hard for banks and regulators alike to know when it’s safe to let traders make bets guided by equations.

In addition, this model doesn’t have to be certain at all times, presumably because all the teams at the World Cup are put through a rigorous quality control system, also known as World Cup Qualifiers, where nearly all 200 odd nations on Earth participate. This goes a long way to ensure that the 32 teams that arrive at the World Cup finals are of a comparable standard. Even then, the worst teams won’t play more than 3 matches, meaning they are less likely to buck the trends in the Poisson model.

The biggest problem here is the very rarity of extreme events. While this simple model is clearly broken, it is very hard to fix it: the German result is totally unprecedented in a World Cup semi-final, which makes it tricky to choose between the many subtly different mathematical explanations that might account for it.

The only sure thing, in footie or finance, is that extreme events are here to stay. In the World Cup, they just add to the excitement; for investors and regulators, taming this uncertainty could be the most important challenge facing the financial system.

This mathematical model suggests the Brazil-Germany result was a once-in-a-lifetime World Cup scoreline, but the Mathematics may be terribly wrong. In the end it was a shock, whatever way you might slice and dice it.