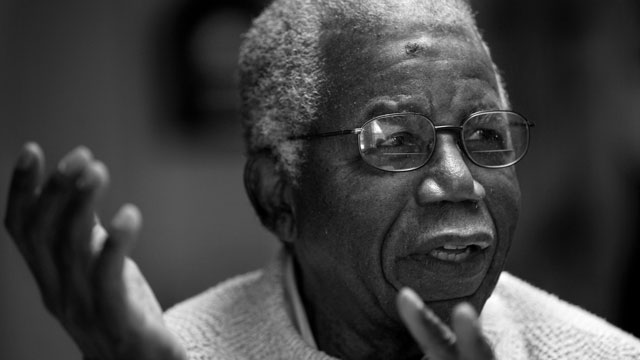

The renowned West African titan of modern literature, Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, has died at the age of 82 after a brief illness.

A statement from his family said his “wisdom and courage” were an “inspiration to all who knew him”.

One of Africa’s best known authors, his 1958 debut novel Things Fall Apart, which dealt with the impact of colonialism in Africa, has sold more than 10 million copies.

He had been living in the US since 1990 following injuries from a car crash.

The writer and academic wrote more than 20 works – some fiercely critical of politicians and a failure of leadership in Nigeria.

South African writer and Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer called him the “father of modern African literature” in 2007 when she was among the judges to award him the Man Booker International Prize in honour of his literary career.

Things Fall Apart has been translated into more than 50 languages and focuses on the traditions of Igbo society and the clash between Western and traditional values.

For inspiration, Mr. Achebe drew on his own family history as part of the Ibo nation of southeastern Nigeria, a people victimized by the racism of British colonial administrators and then by the brutality of military dictators from other Nigerian ethnic groups.

Mr. Achebe burst onto the world literary scene with the publication in 1958 of his first novel, “Things Fall Apart,” which sold millions of copies and was translated into 45 different languages.

Set in the Ibo countryside in the late 19th century, the novel tells the story of Okonkwo, who rises from poverty to become an affluent farmer and village leader. But with the advent of British colonial rule and cultural values, Okonkwo’s life is thrown into turmoil. In the end, unable to adapt to the new status quo, he explodes in frustration, killing an African in the employ of the British and then committing suicide.

The novel, which is also compelling for its descriptions of traditional Ibo society and rituals, went on to become a classic of world literature and was often listed as required reading in university courses in Europe and the United States.

But when it was first published, “Things Fall Apart” did not receive unanimous acclaim. Some British critics thought it idealized pre-colonial African culture at the expense of the former empire.

“An offended and highly critical English reviewer in a London Sunday paper titled her piece cleverly, I must admit Hurray to Mere Anarchy!” wrote Mr. Achebe in “Home and Exile,” a collection of autobiographical essays that appeared in 2000. A few other novels by Mr. Achebe early in his career were occasionally criticized by reviewers as being stronger on ideology than on narrative interest.

But over the years, Mr. Achebe’s stature grew until he was considered a literary and political beacon.

“In all Achebe’s writing there is an intense moral energy,” observed Kwame Anthony Appiah, professor of Afro-American studies and philosophy at Princeton, in a commentary written in 2000. “He speaks about the task of the writer in language that captures the sense of threat and loss that must have faced many Africans as empire invaded and disrupted their lives.”

In a 1998 New York Times book review, the novelist Nadine Gordimer hailed Mr. Achebe as “a novelist who makes you laugh and then catch your breath in horror — a writer who has no illusions but is not disillusioned.”

Mr. Achebe’s political thinking evolved from blaming colonial rule for Africa’s woes to frank criticism of African rulers and of citizens who tolerated their corruption and violence.

Forced abroad by Nigeria’s bloody civil war in the 1960s and then by military dictatorship in the 1980s and 1990s, Mr. Achebe had lived for many years in the United States, where he was a university professor. But he continued to believe that writers and storytellers ultimately held more power than army strongmen.

“Only the story can continue beyond the war and the warrior,” an old soothsayer observes in Mr. Achebe’s 1988 novel, “Anthills of the Savannah.” “It is the story that saves our progeny from blundering like blind beggars into the spikes of the cactus fence. The story is our escort; without it, we are blind.”

The Anambra state government in Nigeria first made the announcement about his death.

Analysts say in Igbo society the death of an important person must be announced by someone in authority.

Nelson Mandela referred to Prof Achebe as a writer ‘in whose company the prison walls fell down’”

Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory

His home state was in mourning for the death of “the illustrious son of the state, Nigeria and Africa”, Mike Udah, spokesman for Anambra state governor Peter Obi, told the BBC.

A statement released on behalf of his family said Mr Achebe was “one of the great literary voices of his time”.

“He was also a beloved husband, father, uncle and grandfather, whose wisdom and courage are an inspiration to all who knew him. Professor Achebe’s family requests privacy at this time.”

Nigeria’s President Goodluck Jonathan said Mr Achebe’s admirers had all learnt “indelible lessons of human existence” from his works.

“Achebe’s frank, truthful and fearless interventions in national affairs will be greatly missed at home in Nigeria because while others may have disagreed with his views, most Nigerians never doubted his immense patriotism and sincere commitment to the building of a greater, more united and prosperous nation that all Africans and the entire black race could be proud of,” the president said in a statement.

Last year, Mr Achebe published a long-awaited memoir about the brutal three-year Biafran war – when the south-eastern Igbo region tried to split from Nigeria in 1967.

After leaving Nigeria, he worked in the US as a professor. His 1990 car accident left him paralysed from the waist down and in a wheelchair.

A statement of the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory said it offered its condolences to the Achebe family.

The former South African president and anti-apartheid fighter, who spent 27 years in jail, “referred to Prof Achebe as a writer ‘in whose company the prison walls fell down'”, the statement said.

One great writer. Will be dearly missed.