May 1 is a holiday that is celebrated or observed by many countries around the world. We translate below an article written on the origins of the May 1 holiday, by a popular Russian blogger Colonel Cassad.

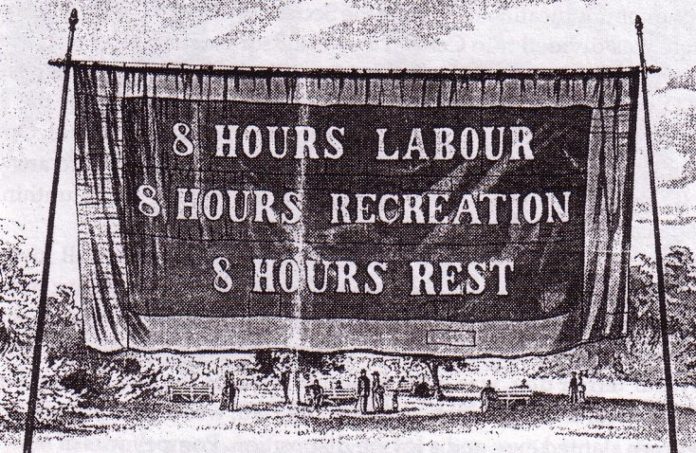

The May 1 holiday has a long prehistory, on May 1 just 130 years ago in the US, Chicago workers at a meeting began agitating for an 8-hour working day, which eventually ended with clashes with the police and bloodshed. In this respect, we can say that in the end, this holiday came to us from America. Later, this date became one of the main holidays of workers of various countries who fought for their rights. In the USSR, it was one of the most important public holidays. Ultimately, this fight was not inconclusive, and many of you go to the usual 8-hour work day largely due to the struggle of the Chicago workers and their followers, hence the classic name of the holiday “Day of international solidarity of workers”, where workers of different countries expressed their solidarity with the demands of American workers.

Of course, the events surrounding this day are now expunged from the holiday’s official commemoration, but it is still useful to remember why this holiday is celebrated on May 1, especially in light of the fact that following the destruction of the Soviet Union, there are forces constantly trying to revise the achievements made by workers, and which forced the capitalist countries to make concession to workers, mainly due to the single fact of the existence of the Soviet Union. The current ongoing protests in France against changing labor legislation clearly shows how relevant today are the demands associated with working conditions.

The meeting at the Haymarket.

The late 60’s and early 70’s of the XIX century – was the time of the creation and the rise of the labor movement in the United States. Trade Unions appeared on the scene, including even a National Workers Congress. One of the main demands was for an eight-hour workday.

The General workers ‘ Congress in Baltimore ( held on August 16, 1866) declared:

“The first and great requirement is the requirement for the liberation of the labor of this country from capitalist slavery by law, which would recognize the eight-hour working day as a normal working day in all the States of the American Union. We have decided to unite all our forces for the struggle to achieve this glorious result.”

After the strike of miners in Pennsylvania in 1868, there was a law adopted on an eight-hour day for workers in government enterprises, however, nearly everywhere it was not observed. The year before in 187, a law was passed limiting child labor to 10 hours a day. In 1860, U.S. industry employed 1,311 thousand workers, in 1880 2,732 thousand workers, in 1900 over 5 million. Immigrants from different countries filled a significant portion of these jobs. In 1873, 460 thousand persons arrived in the United States; in 1879, 789 thousand arrived. Immigrants were a source of cheap labor, as they were content with lower wages. Besides immigrants, women and children were widely used as labor. In 1880, the factories employed about 1 million children aged 10 – 15 years, in 1904 – they employed nearly 2 million children. In 1867, the working day for children was limited to 10 hours. The enterprises did not have any social insurance or benefits in case of accidents during production; neither did they have factory inspections.

In the 1870s, many enterprises forced workers upon employment to sign an “iron oath” that he or she did not belong to any workers organizations.

The first attempt to create a unified organization of the proletariat of the United States was taken in 1866 – but The National Workers Congress after the death of its founder William H Sylvis collapsed in a few years. Another short-lived organization was the Boston League of the Struggle for the Eight-hour Day. In 1869 appeared the organization, The Secret Order of the Knights of Labor. However, its creators imitated the fashion of the masonic organizations and therefore its rules repelled the workers. Joining the secret order required a ceremony of oath, faith in God and commitment to abide by various rules of conduct.

The crisis of 1873 exacerbated the class struggle. The streets filled were with the unemployed, businesses closed, the remaining workers endured reduced wages. Attempts by workers to establish committees of unemployed were brutally suppressed by the authorities, the police and private security agencies were used to suppress the discontent. In 1877, a massive strike of railway workers caused by the lower wages on all lines east of the Missouri was held, and which was attended by more than 100 000 people. Railway workers supported the miners and workers in other professions. Strikes were rolling from one state to another, in several towns, workers took power and created security committees. For the first time in the history of the US, troops were deployed to suppress strikes. In some States, the authorities were forced to meet the demands of workers.

The activities of workers organizations intensified. The popularity of the knights of labor increased after the government due to its repression was able to drive the labor movement into the underground and after the press circulated rumors about the omnipotence and the elusiveness of the organization. In 1879, the Order coming out of hiding, abandoned masonic rituals and headed the labor movement. In 1886, it consisted of about 730 thousand people. However, the leaders of the Order were not ready for a real fight and its influence quickly began to fall. Another attempt to organize a labor movement was the creation in 1881 of the American Federation of Labor under the leadership of former socialist Samuel Gompers, which was ready to negotiate with owners of enterprises. As a result, the U.S. Congress passed laws limiting immigration into the United States, the main objective of the law was to ensure “peace in industry”. In 1890, the AFL consisted of about 200 thousand members, in 1900 about 500 thousand members.

In the early twentieth century there was another powerful mass organization (which still exists today) – Industrial Workers of the World.

During periodically occurring crises, the owners of factories and enterprises either closed their businesses, or reduced wages, fired disgruntled workers and replaced them by workers called strikebreakers. The attempts of the workers to go on strike against layoffs discourage the use of strikebreakers was suppressed by the police.

In 1884, The Congress of American Trade Unions issued a resolution;

“Federation of trades and labor unions of the United States and Canada have decided that from May 1 1886, the 8-hour day will be considered the legal working day, and we recommend that all workers organizations, from this day should merge their demands with this Ordinance.”

The resolution was adopted by those gathered on October 7, 1884 at the Chicago Congress of the Federation of Trade Unions and Workers Unions (founded in 1881), the predecessor of the American Federation of Labor. The delegate of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters Gabriel Edmonston proposed the text of the resolution, and it passed with 23 votes in favor to 2 against. The 25 delegates of the Congress represented eight national and international (USA and Canada) unions – carpenters, locomotive drivers, printers, tailors, etc.

The Federation offered to local organizations the opportunity to hold a vote on holding a general strike in support of demands of an eight-hour working day. The leadership of the Knights of Labor, while agreeing with the requirements of the eight-hour working day, refused to support calls for direct action, and in 1886 forbade its members to go on strike on May 1. The Knights of Labor consisted of more than 700 000 people. The American Federation of Labor was small and made moderate claims. The most radical were dyed in the wool anarchists, who believed that the government would agree to negotiate only when the workers will show their strength and not just ask but also make demands.

The number of strikers in the USA on 1 May 1886.

More than 340 thousand people took part on that day in the movement for the 8-hour working day of whom more than 190 thousand demanded an 8-hour working day, with 42 thousand achieving success, while 150 thousand were able to achieve some reduction of working time without resorting to a strike. In Chicago, the number of strikers amounted to 80 thousand people in New York 45 thousand people, in Cincinnati 32 thousand, in Baltimore 9 thousand, in Milwaukee 7 thousand, in Boston 4700, Pittsburgh 4250, in Detroit 3 thousand, in Saint-Louis 2 thousand, in Washington 1500, in other cities 13 thousand (History of the Labor Movement in the United States . Sixth ed. N. Y., 1951. Vol. 2. R. 385)

Those taking part in strikes (according to different sources) were between 300,000 to half a million people. Many of the strikers succeeded in achieving their demands even before the strike, by declaring their willingness to go on strike, they forced the owners to make concessions.

The events in Chicago

On Monday 25’Th April 1886 in downtown Chicago, a rally was held, convened by the Central Labor Union. Among the main slogans – “the first of May is a working day of 8 hours!”, “Down with the throne, the altar and moneybags!”

The first of May about 40, 000 people went on strike. Albert Parsons, an anarchist and founder of the International Working People’s Association (IWPA) with his wife Lucy and their children, led a March of 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue. In another place in the city, about 10 000 people gathered for a rally. The number of IWPA members in Chicago amounted to about six thousand people; they published several newspapers for workers.

Police officers and members of the city militia, armed with Winchesters, some of them taking up positions on the roofs of buildings along the street observed the demonstrations. However, the day passed without incident. So did the next day. However in one of the establishment newspapers, a call was made to deal with the “main organizers of the unrest” – Parsons and Spies.

The collision occurred on Monday, May 3 at the factory gate of McCormick mechanical reapers. Workers unions at this plant was banned way back in February and when the workers announced a strike, the administration decided to fire all employees and hire in their place strikebreakers. The former factory workers, many of whom were immigrants from Ireland, gathered at the factory gate to prevent the passage of the strikebreakers to the plant. The workers were determined since in last year’s strike they had prevailed over the factory owners, who had tried to bring strikebreakers into to the factory under the protection of the private detectives of the Pinkerton Agency. This time, the police escorted the strikebreakers. About half of the 400 strikebreakers joined the strikers, but the rest went to work. One of the workers activists August Spies urged their comrades to “stand to the end and defend the workers union”.

After the end of the day, the strikers met the strikebreakers coming out from the factory. They met them with insults, clenched fists and threats. The police tried to pacify the workers, using batons and received in response, fists and stones. Then shots rang out. Several workers (from two to six people – official data and eyewitness accounts differ) were killed, several wounded. After a few hours at union meetings, it was decided to hold the next day a rally. In a few hours the Chicago anarchists issued a leaflet in German and English, with a circulation of about 2,500 copies, urging the workers to gather the next day (i.e. May 4), at a rally on Haymarket Square at the intersection of Randolph Street and Des Plaines Street, which was located in the commercial center of the city.

It should be noted that the anarchist leaders of the Chicago workers had their peculiarities: unlike the classic New York anarchists (supporters of the tactics of terror), the anarchists of Chicago were closely associated with the trade union movement and sought to involve its members in the ideas of socialism. The Anarchists in Chicago manifested a commitment to action, as opposed to the position of the Socialist labor party, which excluded itself from work in the trade unions.

The leaflet was in two versions (English and German) and began with the words:

“REVENGE!” ‘WORKERS, TO ARMS!”

The final phrase of the leaflet ended with a call to destroy the hideous monster that wants to destroy you”. The version in German sounded even stronger – “Destroy the beasts in human form who call themselves authorities! Merciless death to them!”

The author of the leaflets was August Spies (1855-1887) – one of the leaders of the Chicago group, the Revolutionary Socialists, a German immigrant who was a prominent trade unionist and the editor of the newspaper “Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung”, he and A. Parsons, were part of the progressive leadership of the main association of trade unions of Chicago – Central Workers Union ( 1889). August Spies subsequently denied that he authored the call for “revenge”. This word, if inserted into the text was made by a compositor of the “Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung”, Podjeve, who, in turn, argued that this was the author’s original. It is also known that at the request of Spies, part of the edition was destroyed and less “bloodthirsty” leaflets were printed, of which about 20,000 copies were distributed.

The leaflets calling to participate in the meeting at the Haymarket May 4

Attention workers!

Mass meeting tonight at 7: 30 in Haymarket, Randolph Street, Beth, Des Plaines and Halstead 4.

The leading speakers will expose the brutal actions of the police, the shooting of our fellow workmen yesterday afternoon. Workers, arm yourselves, we will go forth all together.

The Executive Committee

The rally at Haymarket

The rally began on the evening of May 4 under a light rain on the square and on the street of Des Plaines, where there were about two thousand people. A large number of police officers (about 180 people) observed the meeting. Speaking from the wagon, which was used as the oratorical tribune, August Spies first said that the rally was called not to incite violence and provoke a riot, but to explain the overall situation with the struggle for the eight-hour working day and shed light on the various incidents in this regard.

The rally was held so quietly, that the mayor of the city,who specially came to subdue the passions, did not wait for its end and left.

Of course, the speakers’ spoke of their outrage about yesterday’s shooting, about the need to unite, about the impending victory and the struggle that it requires. The rain intensified, the audience gradually dispersed.

But the police, seeing in the words of the last speaker inflammatory appeals, decided that the it was time to finish the agitation of the workers.

This last speaker (already half past ten in the evening) was Samuel Fielden (1847-?) – a native of England, a socialist revolutionary, an active participant in the labor movement in Chicago. He later wrote:

From the autobiography of S. Fielden

Whatever my doubts about the intentions of the police, they suddenly became agitated, and I thought that I should prevent any possible trouble between the assembled workers and the police. I was on the roof of the car at that moment, when I saw below the police and after Captain Ward ordered the meeting to disperse, although they already had begun to disperse, and without it. I jumped down to him and said, “What’s the matter, captain, it’s a peaceful rally.” I did it in the first place trying to calm the excitement and the nervousness under which he acted, and thus pleadingly showed him that we were not going to create any difficulty. If the captain at that moment had walked towards me, although continuing to insist on closing the meeting, I’d have closed it and assume it all would have ended happily. However, the captain was very rude, ignoring my love of peace, turned to the police, stating as far as I remember: “I order you to close the rally in order to disperse it.” Here is what I think he said then: “I order you to help in the dispersal of the rally”. Since it is a faithful and dispassionate presentation on the course of events at the Haymarket rally on the evening of May 4 1886, I will not argue with him about this, maybe he is telling the truth and I am wrong.

I say possible, because as soon as the captain gave a second order, I jumped off the wagon, from its southern end. Once on the ground, I said, “Well, we’ll leave” or “okay, then, we leave” and headed for the sidewalk. I think I already stepped on the sidewalk when I saw the flash in the middle of the street and heard the explosion of a bomb. Almost immediately, if not quite simultaneously with this explosion, the police opened fire on the crowd. The mob fled in different directions. At the time of the explosion, I was facing south and ran in that direction.

Immediately after the explosion, a bullet hit me in the knee, which came through a bone, changed direction and went out, leaving two wounds. I felt a blow, but did not understand what it was. I with all my remaining strength rushed to the corner of Randolph and Des Plaines after people who were rushing shouting: “Oh, my God! God! Save us!”, and bullets, volley after volley pierced the fleeing people. Turning a corner, I ran in an easterly direction. Once I was safe, I felt pain in the knee and found that, it was wet. I realized that I was wounded. I was looking for my comrades, worrying about what had happened to them, but in the end I went and bandaged my knee.,

The newspaper “Chicago tribune” on the next day reported: “Police went insane from the explosion and become dangerous, as dangerous as any mob, blinded by fear. They fired, making no distinction between civilians and nihilistic-killers”. One policeman was killed immediately and another five were seriously wounded and soon died, another died from the effects of a bullet wound two years later, the injured were about 60 police officers.

Several workers were killed and many wounded, however, the data was not officially recorded, because the workers – the protesters hid their injuries for fear of reprisals.

The same newspaper “Chicago tribune” reported that “a very large number of police were wounded by guns of each other….”.Police captain Michael Shaak wrote that the number of wounded workers was “largely more than the number of wounded police”. In its.assessment, the newspaper “Chicago Herald”, described it as a place of “wild carnage” with at least fifty dead or wounded civilians lying in the streets.

Immediately, searches and arrests of “suspects” began not only in Chicago, but across the country, workers’ clubs and printing houses were smashed.

Soon, eight people directly or indirectly associated with the rally and its organizers from among the anarchists were accused of murder: August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engle, Louis Ling, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Nibe. Seven of them were arrested shortly after the events of May 4, the eighth – Parsons voluntarily came to the police and surrendered to the authorities after learning about the arrest and prosecution of his comrades.

Five (Spies, Fischer, Engle, Ling and Schwab) were German immigrants, the sixth, Nibe, was an American citizen of German origin. Parson and Fielden, were born in the United States and England, respectively.

Two more – William Seliger and Rudolf Snowbelt were charged, but not prosecuted. Seliger agreed to testify in support of the charges, and Snowbelt fled the country before he could be prosecuted. The trial began on June 21. The prosecution argued that all eight people (regardless of any of them throwing the bomb himself) were guilty of killing a police officer and abetting a crime.

The Brother of Albert Parsons argued that there was evidence for involvement in the bomb explosion by provocateurs, connected with the Pinkerton Agency.

A trial jury convicted all eight defendants – and imposed death sentences on seven of them, as well as 15 years in prison for Nibe.

The “quality” of the judicial process is evidenced by the fact that Nibe was not at the rally, where the bomb was detonated.

The Workers activists were not accused of bomb throwing; they were accused of the murder of a policeman at the rally, allegedly because they aroused the crowd with their speeches and activity (agitation and calls for workers to defend their rights).

Parson wrote a letter from Jail

Cell M 25 Cook County Prison

Chicago, July 29, 1886

Whether we live or die, social revolution is inevitable. The limits of human independence should be expanded. The seventeenth century was marked by the struggle for religious liberty, the eighteenth for political equality, and now, in the nineteenth century, humanity requires economic and industrial independence. The implementation of this struggle means the social revolution. We see it coming. We predict it, we welcome it with joy! This is our crime?

… There is no proof that I or any of us had any connection to the murder of police officers at the Haymarket rally. No. However, it was proven clearly that we were all anarchists, socialists, Communists, members of the order of the Knights of labor, Union members. It is proved that the three of us were editors of the working papers, and five – organizers and speakers at the mass rallies of the workers. They, this class, the court, the jury, according to the law and verdict, decided that we should be sentenced to death because, as they say, we are the “leaders” of people who do not accept oppression, slavery, looting and the omnipotence of the monopolies and fight with them. These they recognized as crimes against the capitalist class and found us guilty, and condemned us.

A. Parsons

From the final speech of August Spies at court

Your honor, addressing the court, I speak as the representative of one class to the representative of another …

… If you think that by hanging us, you will be able to destroy the labor movement.. a movement of the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil, working in poverty, waiting for deliverance, – if this is your belief, then hang us! You are trying to extinguish the fire, but here and there, behind you and in front of you, and everywhere flames erupted. This underground fire. You will not be able to quench it.

… These are my beliefs. They are part of my “Id”. I cannot abandon them, and wouldn’t if I could. And if you believe that you can destroy these beliefs, which every day are becoming more common, if you believe that you can destroy them, sending us to the gallows if you want that people were put to death for what they say is true (and try to tell us where and when we told a lie!), – I say, if death is the punishment for the word of truth, then I proudly and fearlessly am willing to pay this high price! Call your executioner!

Eleanor Marx the youngest daughter of Karl Marx, a prominent and active member of the English and International workers movement gave a speech at a rally in Illinois in defense of the Chicago anarchists;

The speech of Eleanor Marx at a rally in the city of Aurora

(USA, Illinois, November, 1886 .)

In defense of the Chicago anarchists

If I were in another place and at another time, I would go directly to the explanation of what we mean by socialism. But in this city and at this point I’d feel a cowardly person, in violation of his bound duty if I did not touch the question which, I am sure, is in the minds and hearts of all gathered here tonight, in the minds and hearts of all honest men and women. I mean, of course, the trial of the Chicago anarchists (and they call it a trial) and the conviction of seven people on the death penalty.

I did not hesitate, loudly, loudly and clearly stating that if the sentence is executed, it will be one of the most dishonest legal murders that ever was done. The execution of these people would just be real murder. I’m not an anarchist, and yet I feel obliged to state it. And my statement expresses not only the view of anarchists or socialists. After all, released only this morning, in the “Chicago Tribune” you will find the statement that “they will hang the anarchists in Chicago,” i.e., that they are going to hang these people, not as murderers, but as anarchists. This is the recognition that we wanted to hear. Not only we, but also our opponents claim that these seven people must die not for what they have done, but for what they said and what they believed.

This cowardly and dishonest sentence should not be carried out. Voices of protest of the working class will prevent it. I at least believe it. If these people are killed, then we will be able to say about these butchers that my dad talked about, those who perpetrated a mass massacre of the people of Paris, and who “are now nailed to the pillory of historical shame, from which they will be unable to obtain release nothwistanding all the prayers of their priests”.

The Verdict and the Execution

ALL EIGHT workers of the activists who appeared in court were without proof convicted of killing a policeman on Haymarket square on May 4 1886

SEVEN of them were sentenced to death by hanging, one – to 15 years of imprisonment.

The sentence imposed by a jury on August 20, 1886, was called into question in the USA and worldwide by a wave of protests of workers ‘ organizations and progressive intellectuals. On September 16, the American Federation of Labor accepted a resolution of protest against the sentence. S. Gompers repeated the protest on 10 November, appealing directly to the Governor Oglesby in Springfield. On 29 September, a protest against the sentence was declared by the chamber of deputies of the French Parliament, 6 Nov – the workers of 49 cities of England and Oscar Wilde, Bernard Shaw, P. Kropotkin, etc all demonstrated against the sentence. On the eve of execution, the Governor Oglesby under pressure from within the US and the world community commuted the penalty of execution to 15 years imprisonment of M. S. Schwab, and Fielden.

Ling committed suicide in his prison cell blowing up in his mouth a fistful of dynamite, carried in his cell under the guise of a cigar (the blast destroyed half of his face and he died in agony several hours later).

On November 11, 1887 Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engle were led in white hoods to the gallows. They sang “La Marseillaise,” the anthem of the international revolutionary movement.

According to witnesses, moments before the execution, Spies shouted:

The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!

In 1893, the three remaining convicted alive were pardoned by the Governor of Illinois and it was announced that all the “Chicago eight” were innocent of the alleged crime.

On their tomb was raised a monument to the martyrs of the Haymarket rally.

As an interesting aside, in 1889, in Chicago at the scene of the massacre, a monument to the dead policemen of the law was raised. It depicted a policeman with his hand up, stopping the crowd of fighters demonstrating for the 8-hour workday. The model for the sculpture of Johannes Gelert the sculptor was a rank and file policeman Thomas Birmingham, formerly among the 175 police officers who stormed into Haymarket square. However, a short while after the opening of the monument, it was revealed that the officer had been “a werewolf in epaulets”: maintaining relations with authorities of the underworld of Chicago and was involved in trafficking in stolen goods. He was dishonorably discharged from the police force. Less than a year after the opening of the monument, were found “unequivocal traces of an attempted bombing” of the monument.

On May 4, 1927, in the 41st anniversary of the events, a derailed tram overturned the monument. The monument was restored and moved to the Park across the street. It had to move again, when an Expressway was built that passed through the Park.

However, the adventure of the monument was not over. In 1968, the statue was doused with black paint. A year and a half, it was blown up and the wreckage washed up on the motorway. The monument, restored urgently, was blown up again the next year. Once again, it was restored, and at the opening ceremony the mayor of Chicago, promised: “the monument will forever remain as a testimony of gratitude of the people to the police”.

The city posted an around the clock guard around the statue, but it was so expensive that in February 1972 ,”the werewolf in epaulets” was moved away from sin, into the inner courtyard of the Police Academy, where from now on, it can only be seen by the police. A police agent the bomber at Haymarket square, Schwab died in 1924 in a hospital for the poor, leaving behind nothing.

This is the story of the events that led to May 1 being celebrated around the world to honor workers and their struggle for equality.

Начало формы

Конец формы