The cool African mist poured its teary drops over the soft black skin of the gentle slopes of Kumawu when Nana Kwame Poku woke up to the early morning choir of the cockerels of his large compound estate. The cockerels with their majestic crowns of gleaming red strode through the compound bellowing the royal call of morning. The sounds of the servants pulling water from the well could be heard amidst the haunting chamber music of the cockerels. In the middle of the compound stood a huge mahogany tree in sacred silence tempered by 300 years of wisdom. The huge mahogany tree was affectionately called The Great One. It seemed so human, nodding with approval or shaking with disapproval when it felt like it. It was a member of the household.

Nana Kwame Poku was an Asante Lord who owned huge farming estates that dotted the rolling hills around Kumawu, worked by his servants and his tenant farmers. The night had fought him refusing to grant him the sweetness of sleep. Those were troubling days of the year 1873. He had been born in 1830 in Kumasi at the royal court of the King. His mother was of the royal clan. His mind was troubled, he could feel the long threads of worry snaking deep in the caverns of his soul. A pale and destructive force was gathering the forces of chaos to destroy the order and balance of his nation, the Asante Confederation. This morning, The Great One even seemed forlorn. It seemed to be wailing as its branches shook violently in portentous warning. There was no wind.

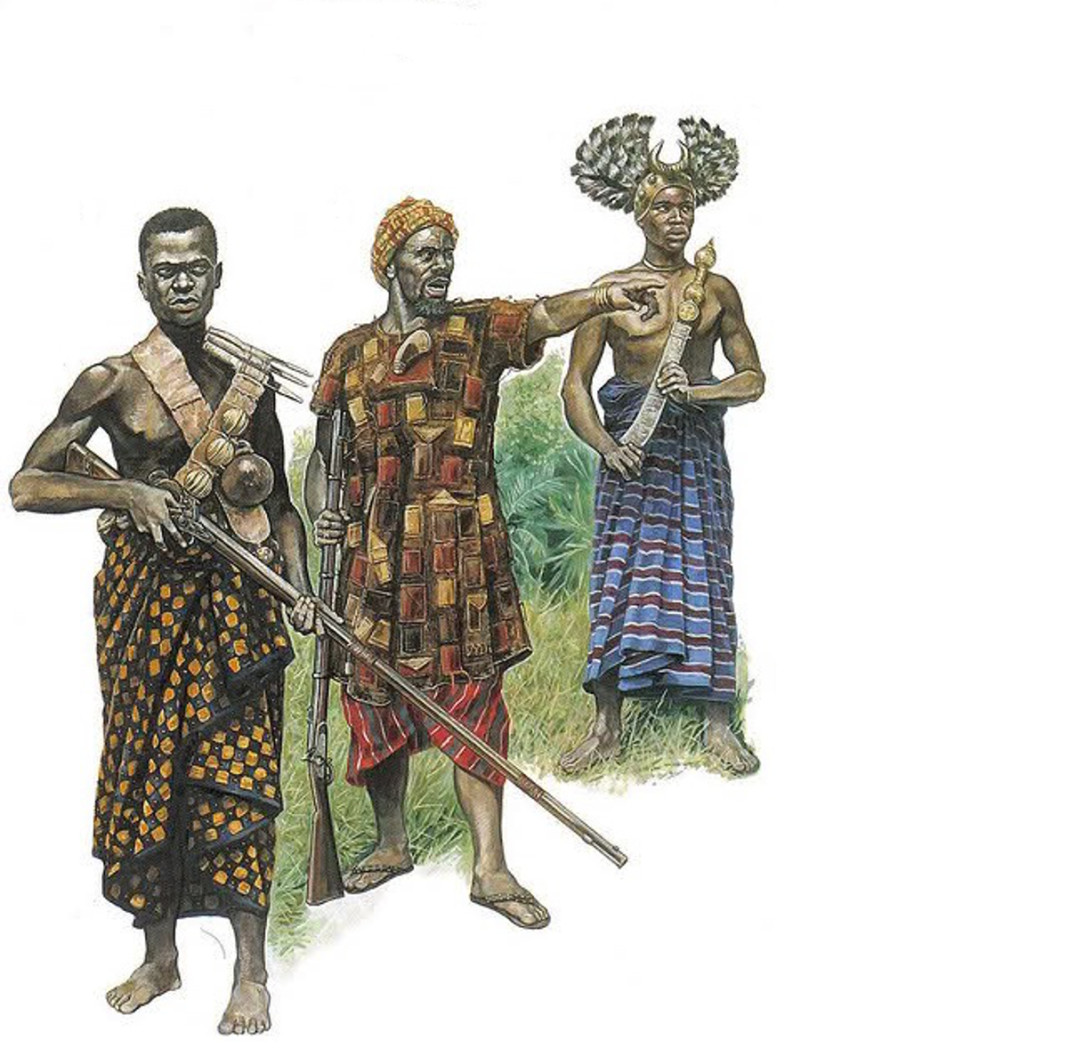

Nana Kwame Poku understood that war was near. He walked out of his compound and took the path leading up to the small hill just north of his compound. He made it up the hill and stood on its crown looking down at Kumawu and the undulating green plains pregnant with the crops of the harvest. He stood alone on the hill for an hour deep in thought. The early morning birds were chirping in the small trees that adorned the crown of the hill like jewels. General Amankwatia IV the commander of the Asante Army had ordered a tactical retreat from Elmina in the young days of December of 1873 after failing to achieve his objectives of taking Elmina due to the outbreak of disease among his troops. He had crossed the river Pra back toward Kumasi. The spies on the coast had reported back to the royal court in Kumasi that a British General had landed on the British enclave of Cape Coast and that the government of the royal court of the white men of England had decided on an invasion of Asante. The white men of England were coming in war. A foreign horde was rousing itself against his nation.

He remembered what his uncle Nana Yeboah had told him. It had been the year 1817. The great King Osei Bonsu, the one called Lord of the Whales reigned in Kumasi. An expedition of four English men among whom was one who appeared to be a young keeper of the memories, Thomas Bowdich. They had come to pay their respects to the King. They had been sent by the English governor of the fort on the coast. His uncle who had had contact with the pale faced men on his trading voyages to the coast deeply distrusted them. The young keeper of the memories Bowdich had assured the King that the motives of Britain were well-intentioned , consisting of nothing more than a desire to share the benefits of English civilization. The King Osei Bonsu had laughed and had asked the young keeper of the memories “Now, how do you wish to persuade me that that it is only for so flimsy a motive that you have left this fine and happy England?” The very next day his uncle had invited the young keeper of the memories Bowdich to his residence and had asked him “Why if Britain was so selfless, had it behaved so differently in India?” His uncle had then described the shocked amazement of the young keeper of the memories about how he deep in the bellows of Africa knew about the workings of the English in India.

Nana Poku kept turning in his mind the words of his uncle spoken to the young English keeper of the memories. It had been 57 years ago. His uncle had long joined the ancestors. But those words had burned deep into his mind. Nana Poku standing on the crown of the hill turned to the East, he turned to the West, and he turned to the North staring into the early morning expanse toward the land of his ancestors where the mighty river flowed from the lands of the great lakes in the heart of Africa. He then slowly turned back to face the South, the wind felt cool on his face, expressionless and grim. Nana Poku started down the hill. The great sun already risen spread its fiery red feathers across the African sky. It was a sunny early morning.

There was a commotion in his house. A messenger from Kumasi had brought grave news. A terrible windstorm had knocked down the sacred tree in the central square of Kumasi. And the insolent English General had sent a message to the King in Kumasi demanding that Otumfuo Karikari withdraw Asante troops from the British protectorate and make reparations to British subjects on the coast and ordered the king to pay an indemnification of 50 thousand ounces of gold and that he would march his army to Kumasi to force the king to accede to his demands. No monarch gifted by the gods of the ancestors to keep at bay the forces of chaos and to maintain balance and order in the nation would accept such demands from anyone. It meant the drums of war were beating. Many of the great chiefs were already in Kumasi. The Kumawuhene had been in Kumasi since November. The King and the Asante Kotoko council had ordered to muster more troops and march to Kumasi immediately. It was January 6, 1874.

Nana Poku stood grimly and listened to the words of the messenger. He strode toward the great tree in the courtyard of his compound. He then turned back and said to his servant Kwaku Kwarteng “Sound the war drum, muster the warriors”. The drums sang sounding the music of war, of battle. Men began to gather. From the bellies of the villages stretching into the misty expanse of land around Kumawu, warriors began to stream into Kumawu. Four thousand warriors gathered from the four winds were organized and drilled. Nana Poku visited the priests of the sacred shrine to ask for the blessings of the gods. The priests gave a reply in heavy measured tones “go honor your ancestors, go with the stool of your ancestors to defend the honor and soul of the nation” He felt troubled. They did not promise victory. He put his mind to the provisioning of the troops and their battle orders.

Finally after ten days the men were ready. On the night before the early morning march to Kumasi, Nana Poku spent the night in the ancestral stool room where all the stools of his ancestors stood guard. He knelt before his own stool deep in thought. Every Asante warrior believed that his spirit resided in his stool. He would fight to defend his stool which he would carry into battle. From the secret place of the stool room, he took the chain of life. The chain of life had been in his family for generation after generation. His grandfather had told him that it was called the Ankh and had been brought by the ancestors from the valley of the great river when they had fled south after the great battle when the last of the sons of Amun no longer sat on the throne of the great God in Ta Meri. He put the chain of life on his neck. He lay his sword by his side and began to softly chant the sacred words as he intoned the ancestors to grant him victory or honor in death.

In the early dawn of January 17, 1874, women and children stood silently by their houses to watch as the armed columns of troops left town. No one cried. The women quietly told the men, return in victory or cover yourself and the ancestors with honor on the field of battle. Nana Poku’s favorite young wife, Ama Serwaa, stood with her little daughter Adwoa by the gates of the compound to watch as her husband prepared to leave for battle. She looked him in the face and said with a strange calmness, “Do not return here in the disgrace of defeat, my voice will not greet you at the gates. Cover yourself with victory against the white men or die on your ancestral stool.” He looked at her in silent communion, then turned to look at Adwoa. He looked around him. He fixed his gaze on the great tree of his compound. He looked again at his little one Adwoa. She was tightly holding on to her mother. The dawn was unusually cool that day.

He then turned to Ama, looked at her and said may the gods keep you well. He then took his place at the head of the column of troops. The great drum sounded and the men armed and in disciplined silence and order left town. Up in the sky, the birds soared. An old lady sighed and remarked, they are performing the dance of the warriors. The birds flapping their wings seemed to wave goodbye to men of which many would not come back alive to native hearth. When the last column could no longer be seen, Ama Serwaa stood still for a long time. Her gaze was distant and her eyes traveled through the horizon of memory. The wind gently kissed her long braided hair. She was a beautiful woman from Ejisu.

Nana Poku and his troops arrived in Kumasi as dusk settled over the sky on January 18. After quartering the troops, he made his way to the royal palace where he was expected in council. The council lasted deep into the night where the chieftains of Asante debated the plans of battle. General Asamoah Nkwanta who at seven score years gray with years and long bearded proposed to fight a defensive battle just south of the small village of Amoafo. The powerful Juabenhene who had brought ten thousand men to Kumasi was angry at this suggestion as he had wanted a frontal offensive attack on the British troops. But Nana Nkwanta’s council won the night and the decision was taken.

General Nkwanta explained to the council his choice of Amoafo and where he planned to concentrate the Asante Army. He said that to attack the Asante army, the white men would be forced to advance through marshy land, drop down into a ravine and then will have to climb up a ridge. He would wait for the horde of the white men on the ridge. Two flanking armies, one which General Amankwatia would command, would circle the English and attack them from the rear. Nana Poku listened quietly to Nana Nkwanta’s plan of attack. Their eyes met and locked in agreement.

On the night of January 30, Nana Poku stood with his troops on a small ridge near Amoafo. The wind was so soft that night. The great star which his ancestors in the shadowy depths of time long past had called Sopdet shone brightly in the night sky. He looked up at Sopdet. It seemed to be twinkling in sorrow. His heart felt heavy.

At 4.00 AM in the early morning the spies that General Nkwanta sent out came back up the ridge to announce that the English troops were advancing. Men silently readied their muskets and their swords. Nana Poku roused his troops and prepared for battle. His ancestral stool stood by his side guarded by his faithful servant Kwaku Kwarteng. There in the distance they heard the bagpipes of the English soldiers. As the clock struck 5.00AM, the battle began. Nana Nkwanta had given the command to a forward detachment of troops to attack the advance guard of the English at the village of Egginassie. But the advance guard of the English reinforced by two companies of troops pressed forward until they reached the ridge where General Nkwanta and the main Asante army waited. It was now 8.15 AM in the morning. Suddenly thousands of muskets opened fire on the English army. There was no wind and the smoke hugged the ground.

The fighting was ferocious. Nana Poku led his troops down the ridge attacking again and again the flanks of the English army pinning the English down and preventing them from moving forward. By 9.30 AM the English infantry had been stopped cold and they began to falter. As the morning grew old with blood, the left flank of the enemy had met a wall of steel and was withering under intense fire. The war chief of the English General Wolseley sent a company of men to aid the left flank but they still could not break through. They run up against Nana Poku and his company of troops. A high ranking officer General Alison reported back to General Wolseley‘s headquarters that there was what seemed like an Asante prince a tall powerfully built man who was at the head of a company of men that fought like ferocious lions. The prince wears what seems like the ancient symbol of Egypt the ankh on his neck. He is a fine warrior. I have seen only few like him in my campaigns in India and the Crimea in Russia. He and his men kept up one of the heaviest fires I ever was under.

The enemy had thrown all their reserves into battle but had been met by a wall of fiery steel and had been stopped dead in their tracks. Their casualties were mounting. General Nkwanta ordered the men to maintain heavy fire. The soft African earth pulsated with the screams of dying men and the smoke of battle rose up into the balmy African sky an incense offering to the gods.

Nana Poku with Kwarteng by his side thrust into the thick of fighting cleaving his way with fire through the ranks of the enemy. Then he heard the sound, it was such a deafening sound that it almost shattered the ears. The English war chief General Wolseley becoming desperate as the tide of battle began to turn against him ordered his officer Major Rait to bring his artillery to the front line and fire in to the Asante frontline. It was the sound and fire of the rockets that Nana Poku head and saw. It was a sight he had never seen before, as they exploded, they tore hundreds of men into pieces at once. He looked grimly at the artillery near the English frontlines and then shouted an order to his men to retreat toward Amoafo. There he would make his last stand.

As the sun rose into its triumph at midday, after four hours of ferocious combat, Nana Poku and Nana Nkwanta’s troops had retreated into Amoafo where the English troops had pressed in and were engaging his men in the town. A messenger run up to him and Nana Nkwanta to inform them that General Amankwatia had died in a desperate charge on the English at the head of his troops on the eastern side of town and that the Mamponghene was severely wounded. Nana Poku turned to General Nkwanta. Both men smiled. General Nkwanta turned with his men toward the eastern part of the town. Nana Poku turned toward the west where the blood speckled sun would set on that day. He told Kwarteng, give me my stool and go as fast as the wind. Let it be told in Kumasi that I have gone to join my ancestors. Let them know in the house of my fathers in Kumawu that the stool of Nana Poku will no longer grace the stool house.

Nana Poku took his stool and raised his sword. His troops clasping their muskets and swords marching in perfect order, their muskets all held at the same angle followed him. With a might cry they plunged into the enemy ranks, men clasped each order in the silent embrace of death. The fateful bullet tore into the chest of Nana Poku throwing him to the ground. He gathering his last strength, took his stool and with his sword in his right hand rushed the enemy ranks for the final time. The sun looked deathly beautiful. As his powerful sword cut down an enemy soldier, another bullet tore through his neck and he fell on his stool.

The name Adwoa escaped his mouth and then he was gone. His warm blood trickled down the stool watering the mournful soft African earth. Up high in the trees, a bird soared up toward the west chasing after the sun. In Kumawu, Ama Serwaa stood still in the compound. The great mahogany tree began to cry violently. Its leaves like tear drops falling. She raised a wailing cry. Adwoa took a fistful of earth and threw it up into the afternoon sky. They fell slowly back to earth little teary drops of black earth.

In Fiahor, Togbi Akpobi Tornu suddenly got up in pain and began to dance the Agbekor. Up in the middle Niger River, a fisherman looked into the waters and remarked, the waters carry evil tidings. On the banks of the mighty Congo the men watched as the river swelled in dreadful sorrow and the trees began to drop their leaves. A young Zulu warrior run toward the Ncome River and thrust his assegai toward the north and then toward the west. On the shores of the Mediterranean as an old Nubian man stood watching, the Nile raised its head and in angry outburst into the sea gorged out a torrent of water. He slowly turned toward the western sky and watched as the fiery forks of the sun’s red tongues began to die. He then muttered “however long the night, the dawn will finally break”. Dusk was setting over the African sky.

Compelling recounting in prose, the history of the once fearsome Asante and the invading hoards from England. Here, Jehuti as a writer is showing a true coming of age. I follow this author on Grandmother Africa for one reason – that I believe, like the men of Asante, every African man deserves a path of growth and the shedding of cowardice. Jehuti has laid it out here in the true essence of an Asante Warrior. That he understands the ethos of the Kingdom of Asante and the men who patrolled her borders, for me, is an inspiring yet humbling comprehension. That, an author like Jehuti Nefekare has grasped, in this short narrative, the embodiment of the bravery of Asante men and the true expectations of Asante women of these men, is gratifying. This story is a must read for you! For your spouses, friends and family. More important, read this to your boys and girls. They must, at the least, grow up like Asante men and Asante women. I enjoyed this and I hope that if nothing at all, this story elevates any African man who reads it to an energy level surpassing that of the Eunuchs our men have been turned into through Christianity and Islam, and the foreign nonsense of materialism and globalization. I hope African men can read this and imbibe our history in all its bravery and candor.

Fascinating story that stands in stark contrast with the reality of today’s African. Like Akosua Abeka says, the essence of the Asante man and the true expectations of the Asante woman stand in contradistinction from the Christian/Muslim Asante man and from the Christian/Muslim Asante woman. Which one of the current crop of leaders in Asanteman, with all their Catholicism, would challenge a Christian/European/American army at the gates? Which one of our Nothern brothers, with all their stake in the expansion of Islamization across the vast expanse of Africa, would fight along the Asantes to hold off invading hoards from the Middle East. None. whatsoever. That is really the sorry state of Africa – and African men and women – in the 21st Century. What needs to happen to change this is clear. But then again, we are sycophants inane to the cries of our Ancestors, to do what needs to be done. Africa must change. But how? As African men, no one is ready to do what is obvious – regain our ‘Africanness’ in all its ‘bravery and candor.’ Perhaps that begins with restoring our LIBATION, for example in the case of Ghana, during state functions. Something, Professor Doctor Evans Mills wiped away in revolt against a custom, a tradition, and a ritual some 10,000 years older than his white mentors who renamed him ‘Evans Mills’, and who refused to teach him to love. The state of the African man in the 21st Century is epitomized by the likes of Goodluck Jonathan, John Mahama and Akuffo Addo, who cannot seem capable of letting Jesus Christ go and help his own people.

Great historical fiction piece, especially the ending which suggests that dawn will break. I’m waiting for this breaking dawn, when the sun rises again over Africa. Hopefully it won’t be a long wait.

These were courageous men who fought in defense of their lands. Their shortfall, ironically, is that they weren’t cruel enough to use a canon. Can you say that to win a war, you’d use any arms possible like nuclear weapons? Sometimes the only thing preventing gains is your morals. I think this was the case here.