The Independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked to the total liberation of Africa.

Jarreth Merz’s film examines, with unprecedented access, the inner workings of the 2008 Presidential Election in Ghana.

Ghanaians, since the fall of the Asante and Dahomey Kingdoms, are very conscious of the role they have played in garnishing African awareness for African socio-political and economic emancipation.

Though every election in Ghana has been viewed from the perspective of the rest of the world, especially in Europe and the US, as an important test to prove that modern African states, like their predecessors, are capable of governing themselves, Ghanaians see it more as a rite de passage for a newly formed nation.

Often the history of civil wars in countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, The Congo, to mention but a few, situate the discussion of modern Africa’s ability to govern themselves without chaos, within a dangerous and parochial mindset.

A mindset that does not fully comprehend the complexity of the modern African state – a problematic footprint left behind by Africa’s short colonial past. The discussion conveniently leaves out the recent and sincere struggle by Africans to reconfigure their traditional states and loyalties into today’s limiting boundaries of modern nationhood.

Boundaries that have come to separate people of the same language, culture, religion, for example, some Akan states, into separate countries – Ghana and The Ivory Coast – and forced them into nationhood with a few Ewes states, who also have sister states split into three different countries – Ghana, Togo and Benin (formerly Dahomey).

Almost to the extent that some families on Ghana’s borders have their kitchens in Togo, or in Burkina Faso, or in The Ivory Coast, and their bedrooms in Ghana.

Hitherto, independent states in Africa have governed themselves as well as, if not better than, most nations across the world.

The advent of the industrial revolution which turned Europeans into a war machine that ferociously forced an armed scramble for the world cannot be left unnoted. That development in Europe led to two unnecessary world wars leaving with it an indelible mark in its wake in Africa. That history, though circumferential, is potent in understanding the modern African struggle for nationhood.

It is within this framework that the politics and the economic struggles of a country like Ghana should be understood and studied.

An African Election succeeds in highlighting Ghana’s struggle – its soul searching for this new nation called Ghana since her independence in 1957 – formed from several fragments of independent African traditional states.

This striving for a new identity underlines the military coups and Rawlings’ 1979 Revolution, or The Uprising, that have become a part of Ghana’s history.

But, having been formed by progressive independent and traditional African states, Ghana has often pushed forward vigorously beyond its internal struggles, wresting independence from the British, and forging herself as a beacon of hope to other African countries experiencing the same identity crisis.

The 2008 Presidential Election therefore was important because it marked the second time a democratically elected head of state would hand over power to another through the ballot box – a unique system of democracy, different from Africa’s traditional forms, also forced on her by the West and the UN in cahoots. But that is another discussion.

Director Merz details the twists and turns of this electoral process in Ghana and the contentious period when neither of the two major political parties – the National Democratic Congress or the New Patriotic Party – achieved a majority. A runoff election had to be held.

The high drama was especially tense during the runoff, with accusations of fraud and vote tampering flying fast and furious on both sides.

But with Ghanaians resolute on ensuring peace and keeping her torch burning high for other African countries to see and emulate, a winner was eventually announced by the commissioner of the Election Council, Dr. Afari Djan.

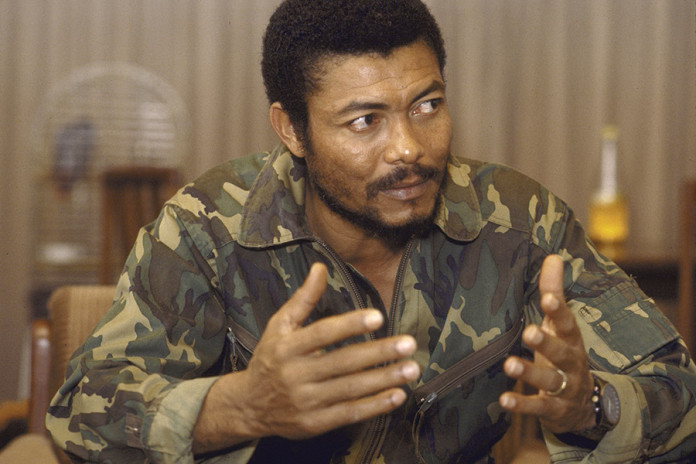

The former President, J.J. Rawlings who had ruled the country through a Military Revolution in 1979, a Military Coup from 1981 – 1992, and through two Democratic Elections in 1992 and 1996, was visibly sitting on tenterhooks the whole period. When he finally sighed with relief he had this to say:

“You cannot deceive Ghanaians. You cannot force yourself on them. Ghanaians will revolt. They have to choose you, not matter how they do it. You cannot force yourself on them.”

Perhaps it is this understanding of the ethos of the Ghanaian population that Rawlings, an Ewe, so much understands. Without pressure he vacated his presidency in 2000 and lives a humble life in a midsized bungalow with his wife, an Akan, often chauffeuring himself everywhere he goes.

There is no doubt after seeing this film that if Rawlings were allowed to stand for another election, and if he wanted, he could deal an easy defeat to any candidate.

Director Merz’s film excels in this penetrating examination of democracy in action in Ghana, especially Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana, which, while not always a pretty sight due to the internal political factions, is still always fascinating to follow and watch.

But to conclude that Ghana’s struggles, like many African countries and their soul searching for identity, can be overcome by quelling internal struggles alone will be false. There’s not doubt that even after independence, the USA and the USSR played major roles in stalling African progress – forcibly removing heads of states and interfering in national affairs.

Ghana suffered at the hands of such a bipolar world but was sparred the chaos of civil wars that it left in many African countries.

Even years after the cold war, the situation has not exacerbated and Rawlings puts it best:

Nothing makes me sadder than when I hear about a nation like the United States of America. Having emerged as the only super power, they are obliged to provide leadership not at the expense of morality. But they undermine it and in effect set in motion despots in third world countries to kill with impunity.

So what they have in effect ended up doing is undermine the culture of democracy everywhere. And you know something. If Americans first taste of terrorism was on September 11, I want to tell them and I have told them several times, we in African have been inflicted with terrorist regimes for decades – before the cold war, during the cold war – and we thought things would improve after the demise of the bipolar world.

Instead it has gotten worse! We thought that maybe we would now see the human face of capitalism. Do you know what Pope John Paul, the late, described it? “The savagery of Capitalism.”

Perhaps, in so many words, what Rawlings seems to capture is Africa’s new and daunting struggle in the twenty-first century – a struggle against neocolonialism and imperialism due to capitalism. Because in its final analysis it seems that America has largely failed to promote a fair world and Africans especially feel they have been at the end of the lashing that America has dealt the world.

But the United States has not been left without its own struggle for a collective identity. The country has failed, either for lack of trying or something close to that effect, to fully integrate their institutions leaving the African American population, who arrived there through a brutal Trans-Atlantic-Slave Trade, subjected to perilous racism, dehumanization, absolute incarceration, and discrimination at every turn.

To that end the United States’ outlook on Africa may be no coincidence, since they have not emerged from the thick shadows of a brutal slave past. Sociologist and former American Sociological Association president Joe Feagin argues that the United States can be characterized as a “total racist society.”

Police harassment and brutality directed at black men, women, and children are as old as American society, dating back to the days of slavery and Jim Crow segregation. Such police actions across the nation today reveal important aspects of . . . the commonplace discriminatory practices of individual whites . . . [and] white dominated institutions that allow or encourage such practices.

Why would The United States of America exactly care about Africa and Africans?

An African Election, is a multifaceted film, one that every concerned citizen of the world should see. And maybe, we can begin the larger dialogue on true sovereignty and fashioning a better direction for the world.

Until then, the African fight for self-determination, though the internal struggles need overcoming, lies largely terrorized day in and day out by those who wield the might of weapons of mass destruction.