The world’s most-watched sporting event, the World Cup, is underway in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Like its sister competition the Olympic Games, the World Cup features unprecedented feats of athleticism and intense levels of competition. It also presents a perplexing dilemma for athletes whose nationhood is in limbo.

Performing on the world stage, every player makes some decision to play for country, but which country? That is the question perpetually facing players who feel bound to multiple allegiances—whether by birth, residence, or family heritage—yet must salute one flag above all.

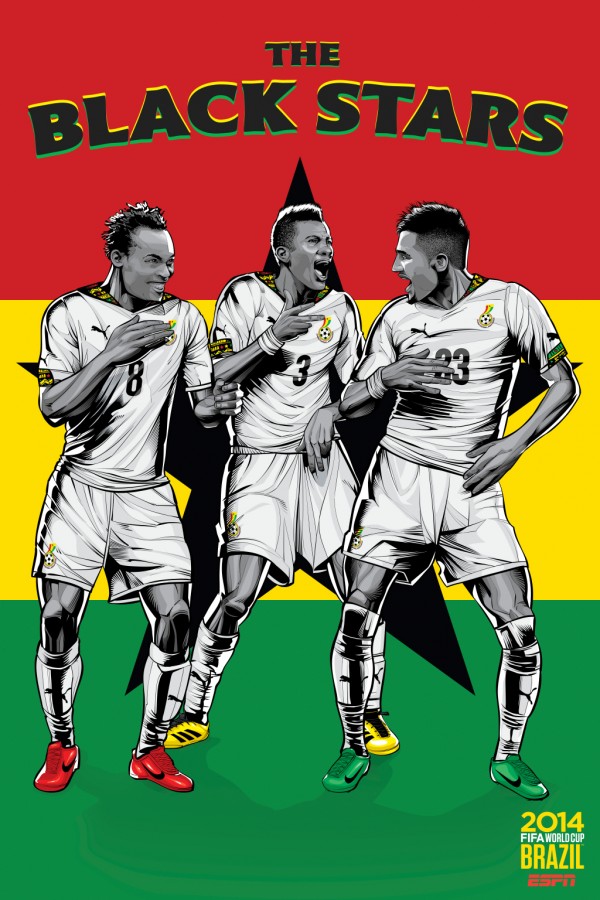

Several players with Ghanaian parents wear foreign soccer boots during this World Cup tournament. Striker Mario Balotelli is the first black player to represent Italy in the World Cup. Forward Danny Nii Tackie Mensah Welbeck plays for England. Defender Jerome Boateng, for Germany.

Some say that Africans should always support their mother countries, regardless of whether they were born or raised on the continent or abroad. Perhaps it should be a no-brainer for these players to side with the Ghanaian soccer establishment, especially since Europeans have been notoriously racist to African players.

Balotelli, for one, has previously received backlash from racist Italian fans. Surely one would rather compete bearing the roots of his parents’ country than even win under the heels of bananas thrown onto the pitch.

As it stands, the choice to represent one’s country is left up to the footballers. They have decided against representing African teams, perhaps to the chagrin of many Ghanaians.

Still others believe that African teams would perform better without these players, as well as without others who spend their careers in Europe only to return home every four years to wear the jersey from an African country. If the decision to play for country resided with the teams and not the players, possibly coaches would only construct teams with players who have never left their native lands.

The case for a truly nationalistic team is made strong when viewed from the perspective of world youth teams. African teams, Ghana and Nigeria in particular, dominate the youth circuit, having won the Olympics and other world junior competitions.

Without trepidation, these teams readily stand against any other team in the world. Collectively, these youth hold the mentality that African teams and players are supposed to win major soccer competitions.

It is only after Africans have played abroad in the Premier Leagues that they develop a mentality that other teams are just as good as theirs.

Perhaps with teams comprised of only individuals who consistently play in Africa, the adults would carry a more confident mentality to the World Cup and not cower in the early rounds of competition.

Rightly so, African teams can only keep their players on the continent if they abandon their makeshift soccer posts on dirt streets and erect soccer academies, develop formidable leagues, and compensate players adequately. Growing up without practicing on a regulation-sized field, it is difficult for African players to feel the full scale of the game, much less master shots from yards away.

Mexico, America, Brazil, and Norway, in fact, most countries have soccer academies. But thus far, of all West African nations, only Cote d’Ivoire has managed to build a soccer academy at the behest of legendary Didier Drogba’s urgency to institutionalize excellence in the sport.

Ghana has midfielders who can field Ballotelli or Welbeck the ball. Boateng could add an additional threat to the Black Star defense. Certainly with these three expats, Ghana would ease into the semi-finals and be the fiercest contender for the World Cup.

Ultimately, the decision to play for country is not made lightly. However greater investment to support an infrastructure for soccer development would likely keep star players at home base, if that is what African nations desire.

Antumwini Specific

Awesome article! This is a very interesting read. African countries have to do better at developing sports. There's something to say about sports and the teaching of character. African soccer players have talent, but character seems to be lacking.