The story of Noah in Genesis, a chapter in the Hebrew Book – The Old Testament – is scant. It is barely enough to write a children’s fairytale about let alone a Hollywood pitch meeting, and much less a feature film.

But Darren Aronofsky has accomplished this feat. In it he has managed to steer clear of the baggage that centuries of brutal racism has bestowed upon it which makes this story one of the strangest and the most unintelligent tales ever told about Africa and about the people of African descent.

During the Middle Ages, Ham was considered by Jews, Christians, and Muslims to be the ancestor of all Africans. Noah’s curse on Canaan as described in Genesis was interpreted by many European and American scholastic leaders as having caused visible racial characteristics in all of Ham’s offspring, notably black skin.

According to Edith Sanders, the sixth-century Babylonian Talmud states that “the descendants of Ham are cursed by being Black and [it] depicts Ham as a sinful man and his progeny as degenerates.” Arab slave traders used the account of Noah and Ham in the Bible to justify African slavery, and later European and American slave traders adopted a similar argument.

At the center of this story on Noah and his descendant is an unnerving example of divine self-doubt and an extreme form of inferiority. According to the Hebrew Book, God – disgusted with his creation – decides to wipe the earth clean and start over again, only to relent and allow Noah, a 500-something-year-old father of three, to save his family and a boatload of animals.

Obviously, many Hebrew and European versions of this tale emphasized a happy outcome: the rainbow, the dove, the cute paired-off beasts, the repopulation of the flood-cleansed earth.

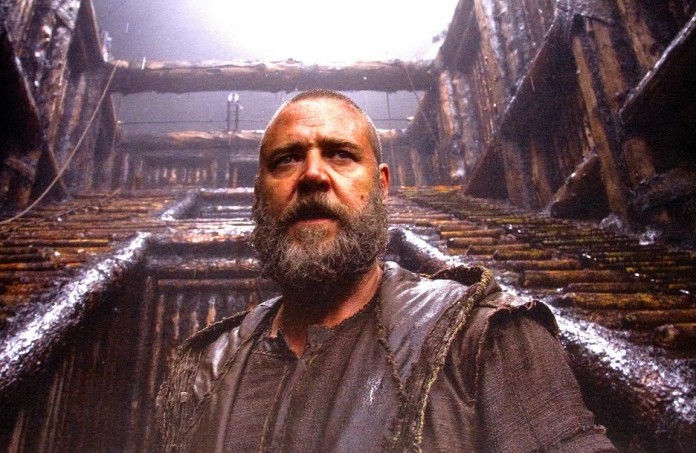

But Darren Aronofsky, in his ambitious fusion of the tale with reality, dwells on the dark and troubling implications of Noah’s experience. Once the waters have covered the earth and the ark is afloat, a clammy fear sets in, for both the audience and the members of Noah’s family: We’re stuck on a boat full of snakes, rats and insects, and a crazy Dad.

Noah, Mr. Aronofsky’s earnest, uneven, intermittently powerful film, is both a psychological case study and a parable of hubris and humility. At its best, it shares some of its namesake’s ferocious conviction, and not a little of his madness.

Even though the scale of this film — the size of its budget and the breadth of its themes — is larger than anything this director has attempted before, Noah is less an epic than a horror film. There are big, noisy battle scenes and whiz-bang computer-generated images, but the dominant moods are claustrophobia and incipient panic.

Noah’s instability — he walks up to the boundary that separates faith from fanaticism, and then leaps across it — is not in the source material, and hardly anyone would be quick to note that Mr. Aronofsky, who wrote the screenplay with Ari Handel, has taken some liberties with the text.

However, that instability with faith, fanaticism and madness cannot be separated from its effects on the nineteenth century and twentieth century madness with racism against Africans.

Hamitic had been a historical term for the peoples supposedly descended from Noah’s son Ham, paralleling Semitic and Japhetic. In the 19th century as a pseudoscience flourished in Europe and America, scientific racism became a lucrative field of study.

Many versions of this perspective on African history have been proposed, and applied (via colonialism and slavery) to different parts of the continent. The essays below focus on the development of these ideas regarding the peoples of Africa.

In the mid-19th century, the term Hamitic acquired a new meaning as many European writers claimed to identify a distinct “Hamitic race” that was superior to “Negroid” populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. The theory arose from early anthropological writers, who linked the stories in the Bible of Ham’s sons to actual ancient migrations of a supposed Middle-Eastern sub-group of the Caucasian race.

To say these theories were false will be an understatement. Nevertheless they fueled a largely Christianized Europe’s attitude towards Africa and her diversity of Vodoo practices especially across West Africa.

Like Europe painted Africa, Darren Aronofsky’s film renders the earlier chapters of Genesis (the snake, the forbidden fruit) as brightly hued hallucinations without form and shape and devoid of civilization. Like the Africa presented to Europeans and Americans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the post-Edenic world is a blasted, desolate, shadeless landscape from which Mr. Aronofsky and his cinematographer, Matthew Libatique, drained every living color.

According to Aronofsky’s interpretation of the Hebrew story, Noah, one of the last descendants of the line of Seth, is a vegetarian and a nomad, camping out on the brown hillsides with his wife (Jennifer Connelly) and their children.

The family is occasionally harassed by marauders from the land of Cain, a people that Aronofsky has charged with blighting the planet with greed and industry, killing off animals and strip-mining precious minerals.

The leader of the land of cain is a shaggy, bellowing warlord named Tubal-Cain (Ray Winstone), conveniently the object of Noah’s justified vengeance as well as of applauding a divine judgment.

But Tubal-Cain is also something of a humanist, or at least a proponent of the idea that humanity, for all its cravenness and corruption, might be worth saving. He has a sly, passionate energy that the terrified, humorless Noah completely lacks.

At the same time it is interesting that in Aronofsky’s version of Noah’s story, it is this Tubal-Cain who tempts Noah’s middle son, Ham (Logan Lerman) – on whom the propaganda of scientific racism has been based for the past centuries – to betray his father.

Tubal-Cain may be a brute and a deceiver, but his nemesis is, at least potentially, a genocidal lunatic to Darren Aronofsky’s credit. The way Noah sees it, he has been chosen not to save mankind but to ensure the annihilation and purging of those who are not chosen.

By portraying Noah is this manner, the film adds to the intense discussion on exceptionalism.

Mr. Crowe has no problem playing this kind of monster in Noah. He specializes in portraying righteousness pushed to the point of murderous, monomaniacal rage.

He also benefits from the presence of gentler, more emotionally flexible performers, and here he has, in addition to Ms. Connelly (in a variation on her role as the capable, patient wife in “A Beautiful Mind”), Emma Watson and Anthony Hopkins.

Mr. Hopkins is gleefully hammy as Methuselah, Noah’s grandfather and the film’s resident wizard. Ms. Watson is Ila, a character invented as the love interest for Noah’s eldest son, Shem (the blankly pretty Douglas Booth), and as a partial answer to the “be fruitful and multiply” imperative. Ila’s presence quickens the ethical dilemma that supplies the film’s dramatic pulse, as Noah is forced to choose between obedience and love, with potentially suicidal results either way.

“Noah” is occasionally clumsy, ridiculous and unconvincing, but it is almost never dull, and very little of it has the careful, by-the-numbers quality that characterizes big-studio action-fantasy entertainment. The riskiest thing about this movie is its sincerity: Mr. Aronofsky, while not exactly pious, takes the narrative and its implications seriously.

He tries not only to explore what the story of the flood might mean in the present age of environmental anxiety and apocalyptic religion, but also, more radically, to imagine what it might have felt like to live in a newly created, already-ruined world, and to scan the skies for clues about what its creator might be thinking.