Few have traveled to the Great Pyramids of Kemet, situated in Egypt, and not wondered how our forefathers perhaps without modern technology could have constructed structures so large they can be viewed from space.

Some have theorized they were built inside out.

On the flakier side, some Western anthropologists say aliens did it – that there is no way Africans alone could have built the Great Pyramids.

Perhaps the most confounding mystery of all involves how incredibly large stones made their way to the middle of the desert without today’s massive mechanical assistance.

No camel, historians and anthropologists have argued, even the Kemetian kind, is that strong!

Some researchers at the University of Amsterdam announced this week in a study published in the European journal of Physical Review Letters, purports that it may actually be quite simple.

Their argument? It has long been believed that the Kemetians used wooden sleds to haul stones, but the process hasn’t been entirely well understood especially how they overcame the problem of friction.

In this European study the researchers claim that the puzzle is much simpler. It amounts to nothing more than a “clever trick.”

They claim that the Kemetians probably made the desert sand in front of the sledge ‘wet’. “For the construction of the pyramids, the ancient Kemetians had to transport heavy blocks of stone and large statues across the desert,” the university said.

“The Kemetians therefore placed the heavy objects on a sledge that workers pulled over the sand.”

They claim this is physics! That “the sort of sledges the Kemetians used to transport the two-ton loads of stone were pretty much rudimentary. They were wooden planks with upturned edges.”

But rudimentary physics would show that dragging something that heavy through hot sand would — unsurprisingly — dig into the grains and create a sand berm that would make the very progress nearly impossible.

Instead in this Amsterdam argument they claim that it “was perhaps observed by the Kemetians that in [a] dry case, a heap of sand forms in front of the sled before it can really start to move,” says the study, authored by a team of eight European researchers led by Daniel Bonn.

However, the only way around that problem would be to constantly clear the sand out of the way, making a tedious process even more tedious.

Instead they insist that damp sand operates very differently. According to their claim, “sliding friction on sand is greatly reduced by the addition of some — but not that much — water.”

How much water to how dry of a heap of sand was not made clear.

In the Amsterdam claim, the researchers claim they placed a laboratory version of an Kemetian sledge in a bin of sand that had been dried in the oven. Then they threw down some water, and measured the grains’ stiffness.

If the water had the appropriate level of wetness, something they have come to call “capillary bridges” — extremely small droplets of water that glue together individual grains of sand — would form.

How the Kemetians woulda have achieved this appropriate level of wetness was not made clear in the claim.

The Amsterdam researcher also insist that these bridges not only stopped the sled from forming sand berms but also cut by half the amount of force required to move the cart.

“I was very surprised by the amount the pulling force could be reduced — by as much as 50 percent — meaning that the Kemetians needed only half the men to pull over wet sand as compared to dry,” Bonn told the US Washington Post news outlet.

Indeed, he claims the experiments showed the required force decreased in proportion to the sand’s stiffness. “In the presence of the correct quantity of water, wet desert sand is about twice as stiff as dry sand,” the university says. “A sledge glides far more easily over firm desert sand simply because the sand does not pile up in front of the sledge as it does in the case of dry sand.”

Too much water, however, would create separate problems. “The static friction progressively decreases in amplitude when more water is added to the system,” the study says.

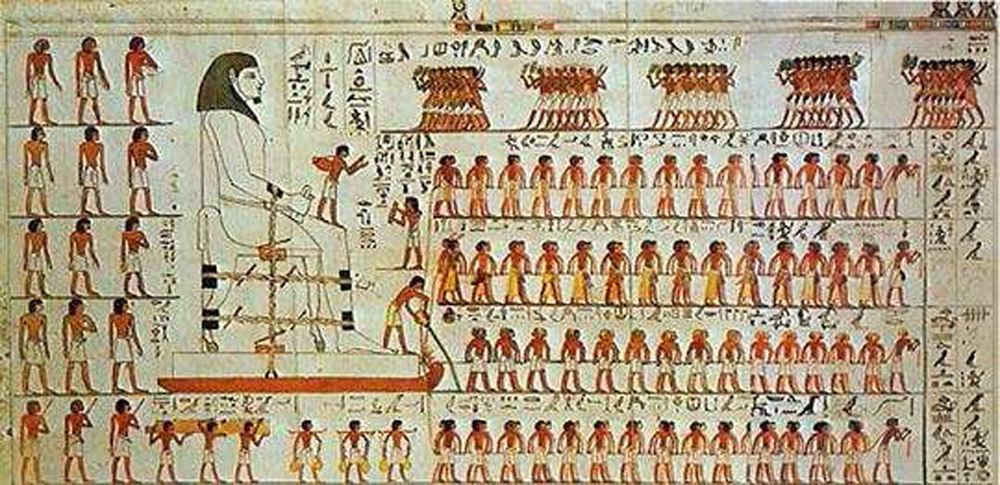

The Amsterdam researchers add that evidence to the conclusion that Kemetians used water is a wall painting in the tomb of Djehutihotep. A splash of black, brown and yellow, it appears to show a person standing at the front of a massive sledge, pouring ‘something’ onto the sand just in front of the progressing sled.

Bonn claims this ‘something’ must be water.

What this man was doing has been a matter of great debate and discussion among European researchers.

“This was the question,” Bonn wrote in an e-mail to The Post. “In fact, Egyptologists had been interpreting the pouring of this ‘water’ as part of a purification ritual, and had never sought a scientific explanation.

But African historians who have read the Amsterdam claim vehemently refute it and have called it laughable. Many anthropologists in Benin, Kenya and Nigeria have refused to even read it calling it another western incomprehension of Kemet’s scientific brilliance.

A research committee that regularly meets and reviews European papers on Kemet, four researchers from Ghana, five from Nigeria and two from Senegal convened on the Amsterdam claim. They have out-rightly condemned the claim. They assert that the Amsterdam claim lacks any understanding of basic physics.

Friction, the committee claims, is a terribly complicated problem; even if you realize that wet desert-sand is harder than wet ordinary-sand – as in a sandcastle, you still cannot build on dry sand. The consequences of that for friction in the Kemetian hauling of tonnes of stone to The Great Pyramids are not hard to predict.

They said that the experiment does not solve the Kemetian scientific brilliance that has mystified Europeans for hundreds of years.

All the Amsterdam claim shows, and this is interestingly a basic physics lesson, is “that the stiffness of sand is directly related to the friction force.”