The facts and forces that have led to the acceptance of Popular Government in the new African States post-colonial Occupation are partly of the Practical and partly of the Theoretic order.

These two forces have frequently worked together; but whereas the action of the former has been almost continuous and unchallenged, it is only at a few instances, civil war and coup d’etat, that the abstract doctrines of democracy have been tested.

It is convenient to examine each order apart, so I pass in rapid survey the salient features of the historical process by which African governments of the popular type have come to man African affairs. Some light may thus be thrown on the question whether the trend towards democracy, now widely visible, is a natural trend for African States, due to a general law of natural progress.

If that is so, or in other words, if causes similar to these which have in many countries substituted the rule of the Many for the rule of the Chief or the King are, because natural, likely to remain operative in the African future, democracy may be expected to live on where it now exists and to spread adequately to other such countries also.

If on the other hand these causes, or some of them, are local or transient, such anticipation will be less warranted. This enquiry will lead us to note in each case whether the change from a desire to be rid of grievances attributed to misgovernment or was created by a theoretical belief that government belonged of right to the citizens as a whole.

In the former alternative the popular interest might flag when the grievances have been removed, while in the latter only when the grievances of democratic government had been disappointing.

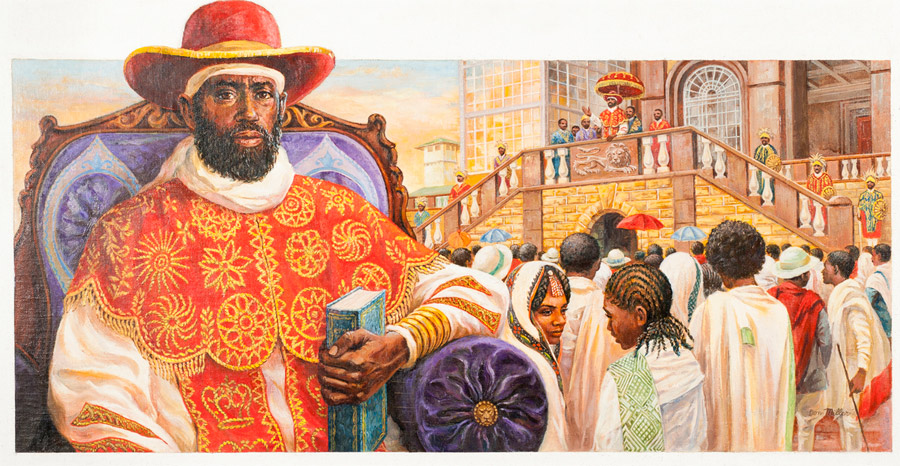

When the curtain rises on Africa in which civilization first appeared, and the ideas of democracy first birthed, Chieftaincy and Kingship is found existing in all considerable states, often alongside a young, but sometimes, vibrant popular government.

This condition has lasted on everywhere in Africa with no legal limitations on the monarch until European colonial occupation in the late 1800s and the first half of the 20th Century.

Selfish or sluggish rulers were accepted as part of the order of nature, and when, now and then, under strong leaders like Sundiata Keita or Sumanguru Kante, there was better justice, or under a prudent ruler less risk of foreign invasion, like Narmer, these brighter intervals in the Ghana Empire, The Mali, The Songhai and the Asante and Dahomey Kingdoms, were remembered as a peasant remembers an exceptionally good harvest.

The monarch was more or less restrained by custom and tradition and by the fear of provoking general discontent. Insurrections due to some special act of tyranny or some outrage on religious feeling occasionally overthrow a sovereign or even a dynasty.

But only a few thought of changing the form of government, like the Kandakes of Kush, the Women Warriors of Dahomey, Yaa Asantewaa of Asante, for in nothing is mankind less inventive and more than a slave of custom than in matters of social structure.

Large movements towards change were, moreover, difficult because each local community was more or less semi-independent, with at least a Chief and a Queen Mother, and had little to do with others. Those who were intellectually qualified to lead also had seldom any other claim to leadership.

In early Europe there were no great monarchies like those of Africa – Kemet, Kush, Ghana etc. Men were mostly organized in tribes or clans, under chiefs, one of whom was a pre-eminent, and sometimes a large group of tribes formed a nation under a king of ancient lineage (perhaps, like the Swedish Ynglings, of supposed divine origin) whom the chiefs followed in war.

In Ancient Africa, the king, for in most of the cities in Kemet and Nubia, the government, which was entirely at first monarchical, power passed for centuries to the heads of the great families by birth.

In West Africa, especially in the four centuries following the 1000s, the arrogance of some of these great families, most notable, Mari Djata II, Mansa of the Mali Empire 1360 -1374, and their oppression of the poor citizens, provoked risings, which in many places ended, after a period of turmoil and sedition, by overthrowing the oligarchy and vesting power in the bulk of the well-to-do citizens (elders of respectable clans), and ultimately (in some states) in all the members of the clans as voters.

These exemplary steps towards democracy in West Africa were not secluded to the region, nor were they the first in Africa’s long history. They came not from any doctrine that the people, all free members of the clan, have a right to rule when they became elders (an elder was sworn into office by popular vote), but from the feeling that an end must be put to lawless oppression by a patriarchal and privileged class.

Equality of Laws in its application to all free members of the clan – equality under the law – was in Africa the watchword of the revolutions, whether violent or peaceable, which brought about major reforms – reforms that affected even Kingship and Chieftaincy and the divine justifications for their long existence in Africa.

Theoretic justifications of the rule of the multitude came later, after colonial Occupation, when politicians sought to win favor by sweeping away the remains of aristocratic government and by filling the people with a sense of their own virtue, power and wisdom.

But the breaking down of the old oligarchy, in the more recent African Kingdoms before colonial Occupation, started even earlier. The growth of large populations outside the old ethnic systems who were for a long time denied full access to the law and sometimes subjected to harsh treatment which their incomplete political equality prevented them from restraining.

These complaints, reinforced by other grievances relating to the stringent law of debt and to the management of the public lands (ethnic lands) led to a series of struggles, which ended in strengthening the popular element of mass politics post colonial Occupation.