Five men in dark business suits gathered before Maria Kiwanuka in a semicircle. They were international bankers and they had a pitch to make.

Ms. Kiwanuka, the finance minister of Uganda, was sitting up on a small riser, her bright pink and gold dress a sharp contrast to the men’s suits.

Bankers are jockeying for the next sovereign debt deal in Africa, a continent that foreign investors have long been wary of for its economic woes, rampant poverty and political instability. Now that narrative is changing, and one sub-Saharan nation after another is jumping into the debt market.

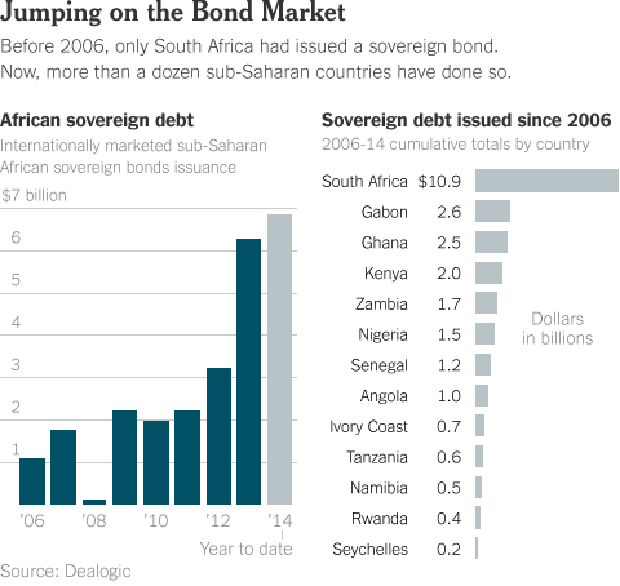

The Ebola outbreak, which is ravaging West Africa, could cost $33 billion, the World Bank estimated, prompting worries about the continent’s growth prospects. But the sovereign debt market is booming, with sub-Saharan African countries raising nearly $7 billion so far this year, more than in all of 2013, according to Dealogic, a market research firm.

The yields on many of the new bonds in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria have dipped even as the Ebola crisis has intensified. That means that the market’s outlook for those countries has improved, although that could change, particularly for West African countries, if health officials’ warnings for the region turn increasingly dire.

The pitch to Ms. Kiwanuka took place at the London office of Standard Bank, based in Johannesburg, during an African investment conference the lender hosted this summer. Only a few days before, the bank was one of three to manage Kenya’s $2 billion debut in the sovereign debt market. Now, it wanted to do the same for Uganda.

“They’re about to make the hard sell,” said an executive in the room, who was watching from a distance.

Uganda could use the money for power plants, rail lines, roads or similar projects it has planned. Countries around the continent are generally using proceeds from the bond sales to improve infrastructure, restructure debt and finance deficits.

Rwanda, for instance, is finishing a convention center and building a new hydropower plant. Senegal is fixing roads and the electric grid. Kenya is expanding its ports and railway system, as well as paying off a higher-cost loan.

After the meeting, Ms. Kiwanuka said such pitches had become routine.

They do want us, and I am flattered that they are acknowledging our macroeconomic stability, because no one wants to get in bed with a basket case,” she said. “I don’t see the sovereign bond as the end of the story. It’s just a tool to get things sorted.

African nations have been borrowing in a variety of ways over the years, issuing bonds on their domestic market and taking out loans directly from foreign banks, as well as relying on aid from foreign governments.

But they have also been known in the West for their inability to repay debts because of wars, political upheaval and economic tumult, leading the U2 singer Bono and the Live Aid founder Bob Geldof to campaign in years past for lenders to forgive African debts. Many sub-Saharan nations are still unrated by the major credit ratings agencies.

Sovereign bonds, which are typically denominated in dollars, can be a far cheaper way to raise money than local lending rates, though they are more expensive than direct aid or low-rate loans from government aid groups, which often come with oversight requirements. Before 2006, only South Africa had issued a sovereign bond. Now more than a dozen sub-Saharan countries have tested the market.

He said:

It shows the opening up of Africa to private capital. It shows that private capital is replacing development aid as a source of capital flows to the continent, and that’s good,” said Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu, the deputy governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, in an interview. He participated in Nigeria’s promotional tour before it issued its first sovereign debt in 2011. “From the point of view of the young man sitting at a hedge fund in London, it’s a new frontier.

But it is not without pitfalls. Because they are borrowing in a foreign currency, countries can quickly find that any cost advantage disappears if their own currency weakens. And investors can become jittery, going suddenly cold on regions, as happened with emerging markets after the Federal Reserve started pulling back on its stimulus efforts.

The appeal to investors is clear enough. Federal Reserve policies after the financial crisis pushed interest rates to record lows, making American debt less appealing and the higher yields offered by emerging market debt more enticing. The yields on sub-Saharan debt can be more than three times as high as those on United States Treasury securities.

But investors, too, face risks. Among other concerns, many sub-Saharan countries have a history of fragile institutions and corruption, and some countries have defaulted on other forms of debt. Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, restructured its debt four times from 1986 to 2000 but defaulted on the agreements nonetheless, according to its debt management office.

“My belief is always that you’re a successful participant in the international capital markets not when you’ve issued your first bond, but when you’ve repaid it, and that time is still to come for all of those large bond issuances,” said Moritz Kraemer, the chief sovereign ratings officer at Standard & Poor’s, in an interview.

Sometimes it is not always clear what the money will be used for. Mozambique’s foray into the market last year was controversial. The country set up a tuna fishing company that raised $850 million through bond offerings, but the International Monetary Fund has raised questions about whether the proceeds were being used for more than tuna boats and asked for more transparency.

For now, bond investors seem relatively unfazed by the potential economic fallout from the Ebola epidemic. While the countries hardest hit — Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone — have not issued sovereign bonds, Ivory Coast, which borders both Liberia and Guinea, received a warm reception when it returned to the market in mid-July. Even now, the yields on its bonds are only modestly higher than when they came to market.

Right now, market conditions are such that lowly rated sovereigns can get access,” said Mr. Kraemer. For a while during the eurozone crisis investors could earn a higher interest rate from Spanish bonds than from those of Zambia, he said. “From our perspective, given what our ratings are, that makes no sense at all.

Many institutions and people, including the International Monetary Fund and Joseph Stiglitz, a winner of the Nobel in economic science, have urged caution.

Mark Roland Thomas, an economist and Africa expert at the World Bank, said the trend “does say something genuine and true about the progress Africa has made in the last couple of decades.”

But he added: “Does it create more challenges and does it mean that macroeconomic management has become more complicated? Does it mean that relatively small economies are now more exposed to international economic conditions? Yes, and our clients are aware of that.”

Demand remains strong, though prices vary.

Ghana returned to the sovereign debt market last month, even as it seeks help from the I.M.F. The country, which in the past has been seen as a beacon of stability, has looked shakier of late. Protesters took to the streets of Accra, Ghana’s capital, this summer as its currency plummeted and inflation soared.

Mr. Kraemer of Standard & Poor’s called Ghana “a cautionary tale.”

Richard Segal, an analyst at Jefferies, said, “Typically, the idea is you would have discussions with the I.M.F. and have them be conclusive, have the I.M.F. make recommendations, have the loan program in place, and then go to the markets.”

But investors flocked to the bond offering anyway, showing more faith than a leading opposition politician who warned that the proceeds would be squandered. Ghana raised about $1 billion with a coupon, or interest rate, of 8.125 percent on a bond coming due in 2026; it is now trading just below 8 percent, compared to about 2.3 percent for an analogous United States Treasury bond.

Ivory Coast priced a 10-year bond more favorably this summer at 5.6 percent, despite defaulting three years ago during a civil war. Investors have become more bullish since the fighting ended and political tensions have eased. The yield on the bond is now slightly above 6 percent.

Uganda, though, is remaining on the sidelines, at least for now.

Our debt service is still below 10 percent of our total budget,” Ms. Kiwanuka said. “We don’t want it to spiral.

A version of this article appears in print on 10/24/2014, on page B1 of the NewYork edition with the headline: An Untapped Continent. Another version appears in the NYTimes By Danny Hakim on October 23, 2014.