NTOABOMA — Is the candidacy of a politician, like Donald J. Trump – the phenome in US politics – an amusing extragenic non-autoreproductive reality TV or a terrifying challenge to centuries of theoretical mathematics? Trump’s popularity and eventual nomination as the Republican candidate for president was dismissed by pollsters and acclaimed statisticians, the likes of whom cannot escape immediate attention. A notable example is the nerdy-playboy Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight who was [I’m not sure if he still is] incredibly regarded as the standard for predicting elections in the US.

But boy, did he miss the target? By nautical miles. Mr. Silver finally admits that, “If the nomination [of Donald Trump] is hard to forecast with a model, it’s just as hard to forecast without a model.” So, why did he try?

Statistics, especially the one used to predict outcomes in elections are predicated on historical data. Nothing more. That is, in order to predict what might ensue, I must know ‘exactly’ what has already happened. And, not just that: I need to know what has been happening in the past for a long enough time if I am to be sufficiently confident with a prediction.

Believe it or not, there’s in fact nothing essentially magical or clairvoyant about statistics but for the hosanna of using existing information to predict information that ties in well [comes closely within acceptable significance levels] with the observed information from which it was gathered. Absurd? Yes. The rest is arithmetic clad in astounding language and artistic manipulation – that is all the mathematics underlying statistics.

Let me walk you through a compendious but chilling example. For five years, I carried water from the tiny tributary of the Volta Lake close to my village, Ntoaboma. Since I was only ten until I was about fifteen. Two miles was what separated this bank stretched along Ntoaboma’s downtown scenery from my home. This was before Ghana’s Rural Water and Electrification project which brought pipe-borne water to the village increased our financial woes. That is another story. I used one of two water buckets – a blue or a green one, my entire childhood for fetching water.

I played a game with my childhood girlfriend. Before I turned the corner to meet her and walked down to the bank together, I would hide my bucket behind the corner of the wall and beckon her to predict which bucket I would use. She would have to shout out “blue” or “green”. If she was correct, I gave her the “agbeli kaklo” I stole from my grandmother’s wooden-glass sieve each morning. I loved the game. The look on her face when she was wrong was priceless. I would munch my stolen “agbeli kaklo” right before her eyes without respect – all malice. God forgive me.

Her job was to predict. My job was to make sure she couldn’t, especially when I missed the window to nab “agbeli kaklo” from my grandmother’s room. In time, as we matured, as smart as she was, like all the beautiful women of Ntoaboma, she got her predictions down to a ‘science’ whether I offered “agbeli kaklo”’ or nothing, or something more ethical. Which only meant that she predicted which bucket I used more often than not. I would grow to learn that women [pardon me feminists] were very good at this, especially when it came to predicting the minds of men. Whatever she had on me, she was spot-on with her predictions and got me in several beatable troubles in my “agbeli kaklo” sting operations. Since I left the village for one of Kwame Nkrumah’s historical boarding schools in Takoradi, I have always wondered how she did it.

One day, I threw her a curve ball – I used an earthenware pot. She didn’t see that coming! From then on she became disinterested in the game. And that was the unspoken end to a game we had both grown to love. She admitted to me, “I am not a magician. I have no idea what you are hiding behind that corner. If you can assure me it is one of the two buckets – the blue or the green one – I can make a prediction. Without that information, I have no way of telling.” She would implore me to reveal. I would grow to understand how conditional all probability and statistics were. Her lessons were astute. There is no such thing as complete randomness. Randomness itself, like chaos, is carefully defined.

She was my first statistician without the trickery of modern mathematics. You must appreciate her complete comprehension for the possible outcomes of her model – that which is close enough [within statistical significance] to what had already happened – the blue or the green bucket! Nate Silver would have failed at what she easily accomplished – with throwing a dice – without the help of the trickery of arithmetic manipulations in mathematics.

But, that is my opinion. Not theory. To accomplish her elliptical conclusions about a blue and green bucket show, today’s modern statistician would need information. That is, they would need to observe me for a period of time; enough time to stabilize the fluctuations of the probabilities with which I used a blue or a green bucket at any moment. “Observe, and observe for a long enough time;” these remain the operative principles in predictive mathematics – what real statisticians call, the ‘frequency of an outcome’.

Which altogether means, Nate Silver and his claque of admirers couldn’t have predicted my earthenware pot either. So, how is the academic statistical methodology any different from what my childhood girlfriend from Ntoaboma employed? No difference.

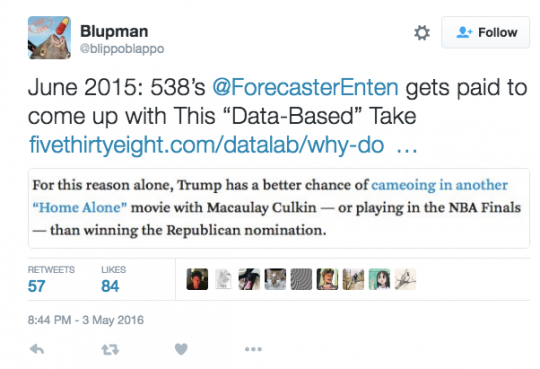

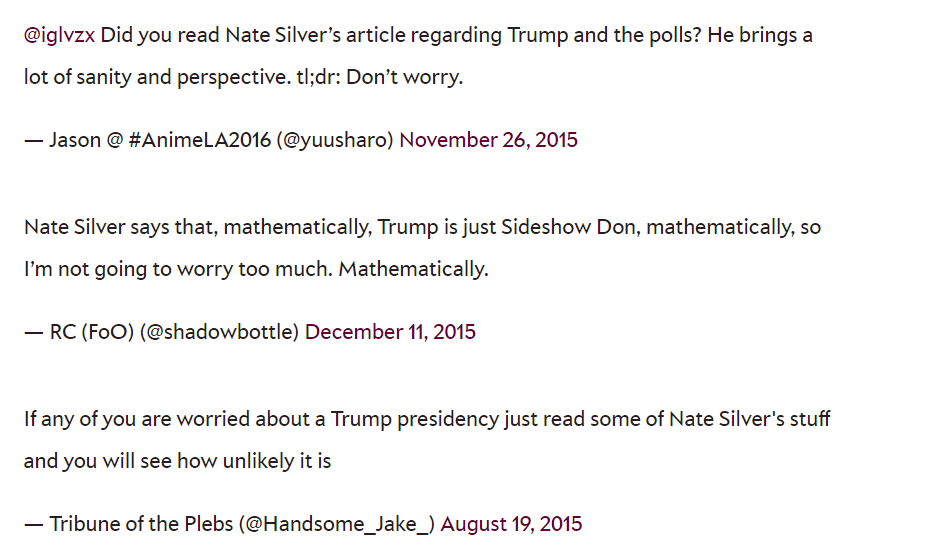

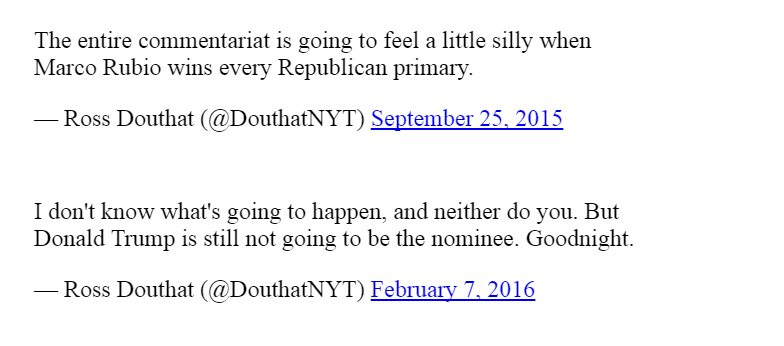

Since August last year Nate Silver and his FiveThirtyEight put Trump’s chances of winning the nomination at 0 percent, 2 percent, and minus 10 percent [you have to be so disrespectful and so full of yourself to assign a negative probability to any event]. That should have been the cue for anyone who thought Nate Silver and co. were actual mathematicians.

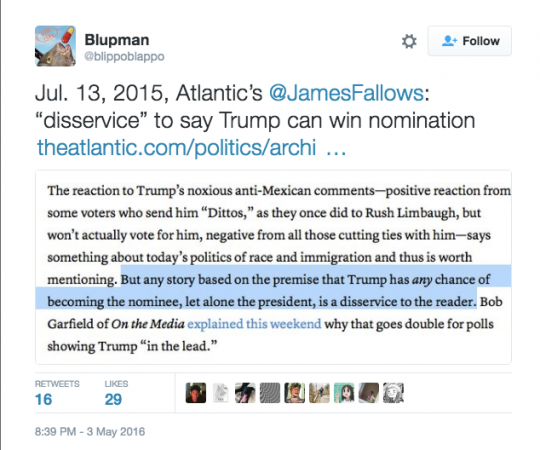

The following month in September, Nate Silver told CNN’s Anderson Cooper that Trump had a roughly five percent chance of beating his GOP rivals. Two months later, he explained that Trump’s national following was about as negligible as the share of Americans who believe the Apollo moon landing was faked. On Twitter, he compared Trump to the band Nickelback, which he described as being “[dis]liked by most, super popular with a few.” In a post titled “Why Donald Trump Isn’t A Real Candidate, In One Chart,” Silver’s colleague Harry Enten wrote that Trump had a better chance of “playing in the NBA Finals” than winning the Republican nomination.

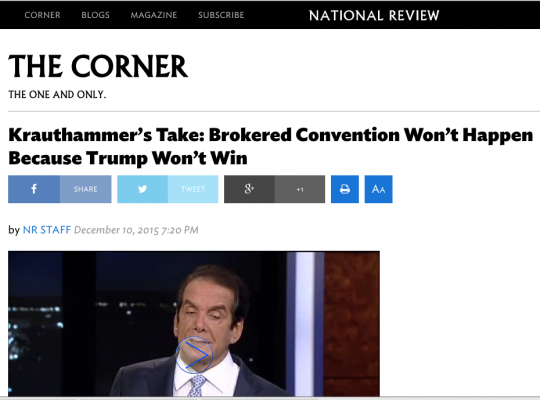

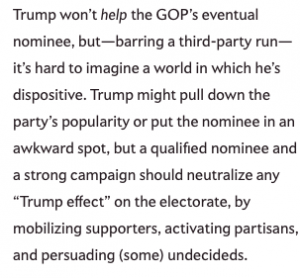

Why do so many political pundits feel a need to spend so much time pronouncing which candidates will or won’t win elections? Multiple times over the past year, Silver has reminded his claque that four years ago, daffy fly-by-nighters like Herman Cain and Michele Bachmann led the republican field at various points. Trump’s poll numbers, he wrote, would drop just like theirs had. In one August post, “Donald Trump’s Six Stages of Doom,” Silver actually laid out a schedule for the candidate’s inevitable collapse.

Since his demise – at the onset of Trump’s rise as the eventual republican nominee – Mr Silver of US elections prediction fame has trudged towards a sobering admission, “Small, seemingly random events can potentially set the whole process on a different trajectory? Those are problems in understanding the primaries period, whether you’re building a model or not.”

Oh really? That is why after Nate Silver and his FiveThirtyEight squadron of quark statisticians failed to call the ‘earthenware pot’ [Donald Trump] in the republican primary, they needed to admit it and stop parading themselves as mathematical geniuses [magicians] who just missed a piece of the puzzle. There’s no puzzle. All the unfounded excuses will not turn statistics into magic.

It is entirely a different kind of error when one invokes mathematical authority and expertise when issuing such embarrassingly wrong pronouncements, and, worse still, when the tone used is one of certainty and hubris as though the decrees are being passed down from Amen-Ra.

Almost all statisticians – the likes of my childhood girlfriend, who failed to call my earthenware pot and is now an architect building affordable homes with earthenware materials – who missed the phenome that is Donald Trump and how he trounced every statistical model, should throw their hands in the air out of frustration and say once and for all, “We are not magicians.”

Nate Silver was subject to the same biases as the pundits who missed it. In particular, he was anchored to his initial forecasts and was slow to update his priors in the face of new data. My childhood girlfriend would ask, “Are you holding a blue or a green bucket?” If the answer was yes, she would make a prediction. If the answer was not forthcoming, she knew she stood no chance and abandoned the idea of prediction altogether. She was sincere in her assumptions unlike Nate – as his eyes mist over his encomiums during his often ruthless predictions.

Trying to predict the future can be fun, which is why — from office cubicles, from hip-hop party pools to Wall Street stock market speculation — many, who think they know some mathematics, do it. Usually, though, people, like Menes Tau of Grandmother Africa who rightly predicted Trump’s win, make such predictions with at least some level of humility: with the knowledge that they could be wrong, or more that they do not actually know what the future holds.

But Nate Silver and the rest of his slobbering sycophants, who think they are mathematical geniuses, cannot be sincere. They are swollen-headed about being branded “geniuses” – whatever that means. So, they find themselves selectively interpreting the evidence and engaging in lazy reasoning. They, and not Trump, are actually the terrifying and dangerous challenge to centuries of theoretical mathematics. They are, after all, just nincompoops – as ignorant as the next dead-wrong pundit hiding behind a cloak of astounding manipulations in mathematics.

A wonderful piece from Narmer Amenuti yet again. There’s order in the chaos for those who choose to abide by theoretical frameworks and shun the temptation to become prophets that they are not. Many have fallen prey to predictions because they fail to appreciate that statistics itself is not an exact science. Great read!

Great. But, is the idea here that nothing is predictable?

The idea here, from what I understand, is that nothing [no truly random event] is predictable with statistics. I guess by predictable we mean can anyone with the help of mathematics predict anything [any random event] with certainty? No!

Why then is Statistics everywhere in every graduate program, or even most undergraduate programs, held in so much praise?

It depends what you mean by Statistics. If by statistics you mean the study of the frequency and probability of outcomes in a random event or if you mean the prediction of outcomes of random events? There’s a difference although professors love to stress the predictive power of the mathematics more than anything else. But a dose of statistics is fully warranted. It is, I will say necessary. It shed light on existing data which is where it is most powerful and helps in the organization of new information. If the predictive powers are taught with some humility, Statistics is a fine subject.

As in the case of Trump, like the earthenware pot, the field humbles anyone who jumps ahead of themselves. This is why the study of any topic in science requires the definition of strict boundaries. The more defined the conditions the better the study. In this case, Trump, or the occurrence of Trump, like the earthenware curve ball that Narmer threw his childhood girlfriend, was not in the consideration of many of the statistical models used in predicting the primaries in the US. Nate Silver should have seen that a long time ago. Instead he went on fooling the masses as if he was God.

So statistics is not an exact science?

What is an exact science?

Like physics. As in predicting what the acceleration due to gravity will be on the Pluto? We’ve never been but we can know, for sure. or?

I see. You’ve asked a big question. I am not sure if we necessarily “predict” acceleration due to gravity. We’ve technically come up with a way of measuring a vector quantity on Earth. If this way of measuring it is consistent all around Earth, and say on Mars, we might be able to predict within confidence the acceleration due to gravity on Pluto, although we’ve never been. And we can be exact. But this does not necessarily mean that because we can predict that for Pluto, we can predict the acceleration due to gravity on any planet in the universe. That is where confidence based on the assumptions of the model begins and dies. Not every proposed explanation is acceptable merely because it embodies a deductive structure.

“Not every proposed explanation is acceptable merely because it embodies a deductive structure.”? What? Gee…

For example, no one is likely to regard as satisfactory a proposed explanation for the fact that Trump actually led in at least one poll which cites the further fact that Trump actually led in all the polls [he won] – even though the former statement follows logically from the latter.

Discussions of this magnitude go back to ancient Kemet, and a large variety of such additional conditions have been suggested. These conditions can be classified in three parts: logical, which specifies various formal requirements for explanatory premises; epistemic, which stipulate in what cognitive relations one ought to stand to the premises; and substantive, which prescribe what sort of content (empirical or otherwise) the premises ought to have.

Statistics is good at the logical, and tends to underestimate the epistemic in its modeling. In that way it fails substantively whenever it must grapple with a little chaos. But that is just the limitation of the mathematics. Nothing extraordinary.

My inactive on line for a while is as a result of my tablet and laptop, was stolen out of my car at the campus 2days from today. Hence place me in a kind of inconvenience. But will respond to this your essay soon.

So this draw me back to one of my reasons why i abandon econometric practice and followed the path of paxeological theory defind by Prof. Mises under the Austrian School of Economics. Why because it is not easy to predict the future of man based on only historical data. Man behaviour and decisions are affected by many variables in a scientific studies: for example the current environmental circumstance will probably be different from the circumstance of the past, hence will lead to variation of decisions. What statistics seek to do, is to provide perfect environment which in the normal circumstance difficult to occur on this earth especially in a programme like social science studies & practice . Such is the reason why, they give experimental conditions: with “if” clause, concluding that “if all things be the same” they believe the result should be as prescribed. Hence if such parameters are not met, his/her expected result could not be achieved. Critical looking at the attitude of empirical science especially in the discipline of social science one could easily conclude, most scientist in this faculty are in a game of mind play, hence could not be trusted fully in the science of prediction to the future, depending strictly on empirical figures rigorous of historical fact.

My publication title “Entreprenomics” dive deeper into the science of futurology in Social Science discipline under the principle of behaviourial economics and it vital role it plays in Market Phenomena…..deepening the understanding of the praxeological theory within the African terrain.

The idea that statistics can be used to predict the future is as false as the sobering belief by the ancients that the earth was flat. Whatever their calculations, from where they stood, the earth was indeed flat – flat enough to confuse the hell out of them that it was actually curved.

Statisticians are like the ancient giants of geometry who called the earth flat. Sure it is, and it is not. Herein lies the conundrum from where statisticians stand. Information at hand is only worth the information at hand and nowhere else, for sure. From data, a mathematician can deduce a trend, assign a model, an explicit function even, that describes the data from where it begins to where it ends – the boundaries. That’s it. It will be nice if it stopped there.

But Statisticians, not all, often extrapolate, like the ancient geometric specialist of our ancient past. They cannot tell that if you traveled far enough, the flat land curved. But extrapolate they do anyway. Who cares. No one can arrest them. Good mathematicians understand they cannot be 100 percent certain about extrapolations [confidence] no matter how great their models are [significance]. Bad mathematicians take statistics to mean magic, and gallivant the academic and public terrain terrorizing the rest with inane models of historical data. Nothing is to be learned in the future in any model. All that a wonderful statistical model can do is help understand what has already transpired. Hindsight they say is 20-20, and statistics is what helps to achieve the kind of vision.

Does the mathematics have power. It does. To plan for the future you should be concrete on what has already transpired. Statistics helps you plan, very well, to near perfection even. But it doesn’t tell you what will happen in future.