I’m over it: Immigrant Literature

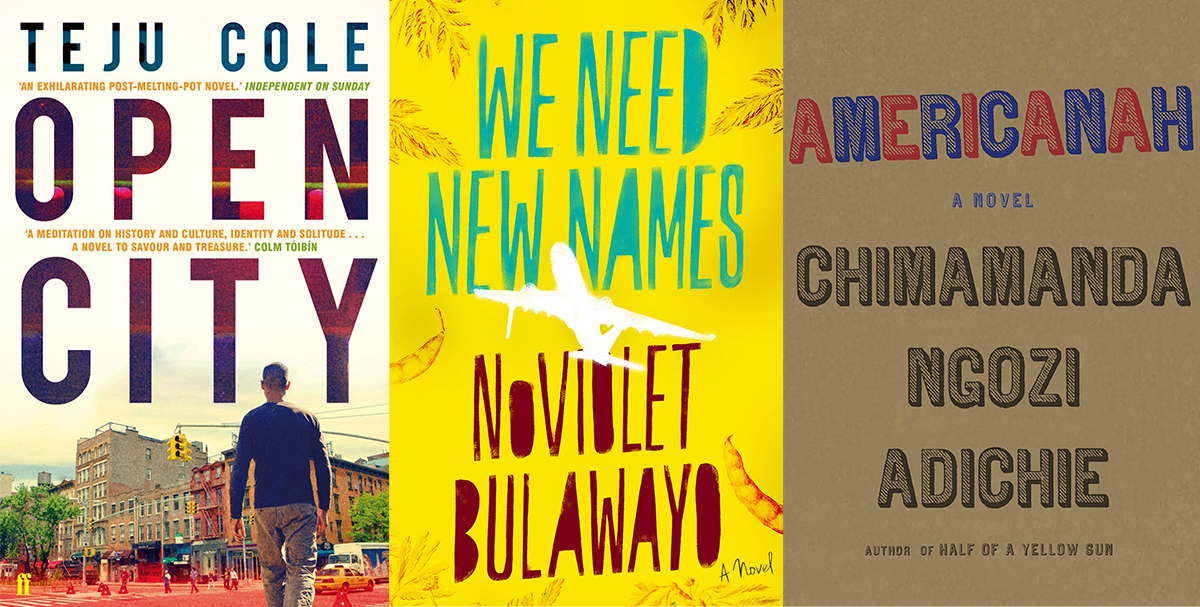

I don’t know when it happened. It might have been somewhere in the middle of Teju Cole’s Open City, as I followed his protagonist around the streets of New York. Or maybe it was at the end of NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, when I boarded the flight to America with its precocious star. Or perhaps it was a few weeks after finishing Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, and I had finally begun to forget the stress carried by illegal African immigrants in Europe.

Whichever way it happened, it happened. And I found myself flinging my copy of The Granta Book of the African Story across the room, vowing to never read a piece of African Fiction again, or at least its “Afropolitan” variety.

Let me explain.

This month I made it to a list whose existence I was previously unaware of: Ventures Africa’s “15 African creatives to watch out for in 2016.” As I scrolled through it, I felt a surge of pride. I was proud to be one of the only people on that list who was not “London-based” or “Brooklyn-born.” The act of being an African living in Africa seemed to me at that point to be almost revolutionary. I cannot hide the small and perhaps arrogant joy that comes to me when I know that all I create is 100% inspired by my uninterrupted African life.

And that’s why I flung my copy of The Granta Book of the African Story into the darkness of my disorganized closet. I just couldn’t take it anymore. I couldn’t get over the fact that my first encounter with Alain Mabanckou’s work was a foot-chase in a Paris subway station (The Fugitive). I couldn’t take a single new story that demanded I imagine the streets of Haywards Heath (Aminatta Forna). And for the love of God, if I had to read one more story that ends with the African protagonist being whisked away to America, I was downright ready to spit!

Where did this all come from? I can’t say for sure. Perhaps I had begun to truly believe that the importance of African literature was to connect us ordinary Africans to each other’s lives. It may have also been my encounter with the dismal African fiction section at O.R. Tambo Airport’s Exclusive Books: it had only three books, and they are all mentioned in the first paragraph of this article!

Or maybe, it was my recent encounter with the empty shelf at Botswana Book Store: a shelf that had previously housed a hundred books from the Pacesetters series. The Pacesetters series was a collection of books written by Africans from all corners of the continent. It ran between 1977 and the 1990’s. The stories were rarely over 200 pages long and featured fast-paced thrillers, romances and mysteries almost all set in the fast-growing cities of 1980’s Africa. The books cost around 50 Pula and were fun to read on particularly hot afternoons.

The Pacesetters series was really special. And only now, standing in their former section in the Botswana Book Centre, did I realise why. They were written for me. For three decades these books had been doing a very simple job: entertaining numerous ordinary Africans by telling exciting stories in environments we could imagine. They were not competing for the Man Booker Prize, and probably wouldn’t make the cut for any contemporary short-story competition. But that’s because they weren’t written for the White gaze. They were not made to explain Africa to half-curious American housewives, or home-sick African students in UK. These books were written not for the purpose of lifting a mirror to the European psyche, nor did they need to tell yet another tale of the New York immigrant experience. The Pacesetters series sought to entertain, but in doing so ended up connecting.

All of this, all of this, all of this made me wonder why I had to read one more story about America. Or France. Or Britain. Actually it made me furious. Yes, I respect what contemporary authors are trying to do: share their experiences. That their experiences are not particularly original is probably only true to me. After all, everybody is sure what they have gone through is very unique.

But African Literature cannot move forward if we celebrate themes that are centuries old. More explicitly, African Literature cannot move forward with the most celebrated authors writing about Europe.

One more thing:

Enter, Diary of a Zulu Girl. Diary of a Zulu girl was (is?) a Tumblr page that was started by an anonymous South African who wrote (almost in SMS lingo) about the adventures of a girl who had moved from Kwa-Zulu Natal to Johannesburg. It included the sex-filled adventures that would follow. The story itself was not necessarily new: for as long as people have been moving to big cities, they’ve been writing about the consequent corruption of their innocence.

But, this was new because it was online. It was free. And my god was it addictive! One night I sat in my room for five hours straight, scrolling through chapter after chapter, my proverbial pearls firmly clutched. I couldn’t get enough of it. And neither could tens of thousands of Africans.

So we do read, but guess what? We don’t read so we can accompany you as you dissect the peculiarities of Americans or Brits or French Blacks. We read, at some level, because our stories are worth connecting to: our stories are all we have in this cold world. Let us read them!

Africans in the diaspora equally have the write to tell their stories and share their experiences. I don’t think literature most importantly fiction should be bound by geography. This kind of argument is what leads to pigeon holing of African writers. Don’t write this, don’t write that. The African experience is universal, it is not bound to the continent alone.

But isn’t what is being spoken about the wish to use one’s own gaze and owning that gaze? To someone who’s experience its Eurocentric or the like its an alien gaze used to invalidate. It takes confidence to own and accept one’s gaze. Its not a way to alienate whilst owning which the “Afropolitain” tends to.

It is no less true in this African kingdom of literature than in the West’s kingdom of literature, that no man shall enter into it except he become first as a little child – a student. Ms. Mohutsiwa’s point is a tad bit bold, nonetheless it alludes to writers (African writers) who approach Africa, from their very first writing in the West, as if they already knew all of it – they write about and come into our kingdom as professors, teachers and preachers, even from abroad, since their peculiarities abroad have been so celebrated by the Voyeur, that it grants them a license to speak of Africa in another dialect. Although from their writing they were never really here grounded.

Right on, Akosua! I do believe the author wants us to understand that their perspective is their own, but their knowledge of Africa is questionable and shaky, although they try to act as though they are the gatekeepers on the subjects. I don’t think people who are in Africa tend to bias their works over others but just that people outside of Africa maybe are trying to make up for their distance by speaking the loudest. We should also question what books get the most press. Usually the ones with western-African writers, so I think the author also wants us to keep that in mind.