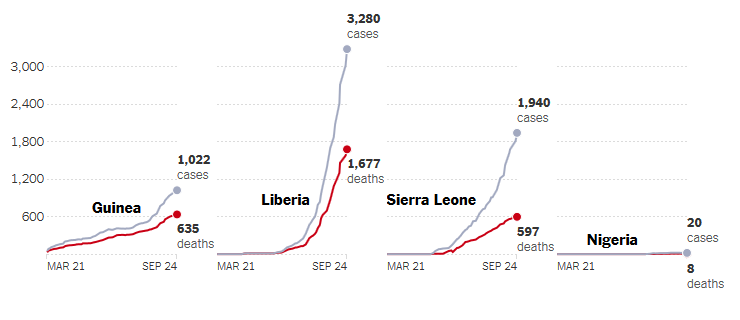

How many people have been infected?

More than 6,200 people in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone have contracted Ebola since March, according to the World Health Organization, making this the biggest outbreak on record. More than 2,900 people have died.

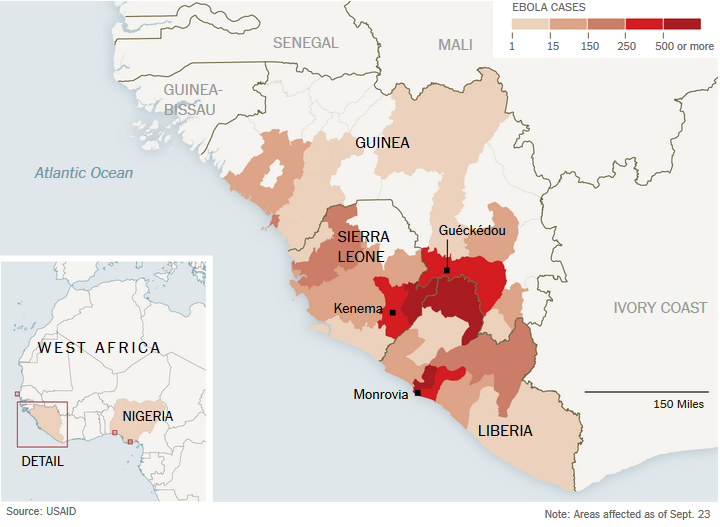

Where is the outbreak?

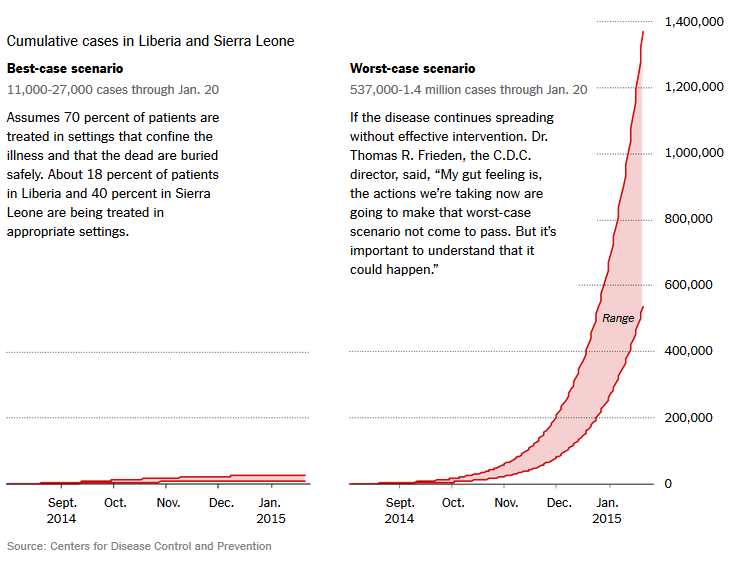

How big can the outbreak become?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday that in a worst-case scenario, cases could reach 1.4 million in four months. The centers’ model is based on data from August and includes cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone, but not Guinea (where counts have been unreliable).

Estimates are in line with those made by other groups like the World Health Organization, though the C.D.C. has projected further into the future and offered ranges that account for underreporting of cases.

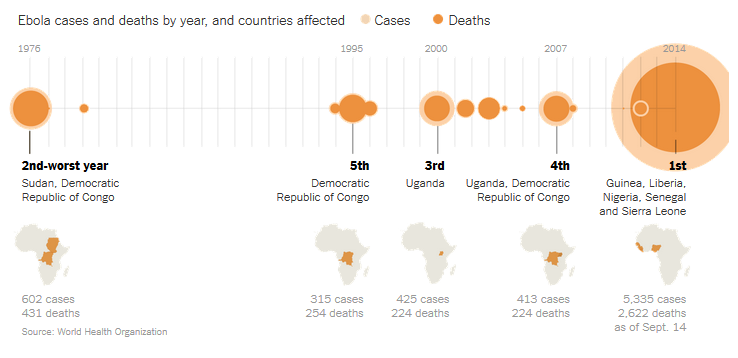

How does this compare to past outbreaks?

It is the deadliest, eclipsing an outbreak in 1976, the year the virus was discovered.

How contagious is the virus?

You are not likely to catch Ebola just by being in proximity to someone who has the virus; it is not airborne, like the flu or respiratory viruses such as SARS.

Instead, Ebola spreads through direct contact with bodily fluids. If an infected person’s blood or vomit gets in another person’s eyes, nose or mouth, the infection may be transmitted. In the current outbreak, most new cases are occurring among people who have been taking care of sick relatives or who have prepared an infected body for burial.

Health care workers are at high risk, especially if they have not been properly equipped with protective gear or correctly trained to use and decontaminate it.

The virus can survive on surfaces, so any object contaminated with bodily fluids, like a latex glove or a hypodermic needle, may spread the disease.

Why is Ebola so difficult to contain?

The epidemic is growing faster than efforts to keep up with it, and it will take months before governments and health workers in the region can get the upper hand, according to Doctors Without Borders.

In some parts of West Africa, there is a belief that simply saying “Ebola” aloud makes the disease appear. Such beliefs have created major obstacles for physicians trying to combat the outbreak. Some people have even blamed physicians for the spread of the virus, opting to turn to witch doctors for treatment instead. Their skepticism is not without a grain of truth: In past outbreaks, hospital staff members who did not take thorough precautions became unwitting travel agents for the virus.

How does the disease progress?

Symptoms usually appear about eight to 10 days after exposure, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At first, it seems much like the flu: a headache, fever and aches and pains. Sometimes there is also a rash. Diarrhea and vomiting follow.

Then, in about half of the cases, Ebola takes a severe turn, causing victims to hemorrhage. They may vomit blood or pass it in urine, or bleed under the skin or from their eyes or mouths. But bleeding is not usually what kills patients. Rather, blood vessels deep in the body begin leaking fluid, causing blood pressure to plummet so low that the heart, kidneys, liver and other organs begin to fail.

How is the disease treated?

There is no vaccine or definitive cure for Ebola, and in past outbreaks the virus has been fatal in 60 percent to 90 percent of cases. The United States government plans to fast-track development of a vaccine shown to protect macaque monkeys, but there is no guarantee it will be effective in humans. The question of who should have access to the scarce supplies of an experimental medicine has become a hotly debated ethical question. Beyond this, all physicians can do is try to nurse people through the illness, using fluids and medicines to maintain blood pressure, and treat other infections that often strike their weakened bodies. A small percentage of people appear to have an immunity to the Ebola virus.

Where does the disease come from?

Ebola was discovered in 1976, and it was once thought to originate in gorillas, because human outbreaks began after people ate gorilla meat. But scientists have since ruled out that theory, partly because apes that become infected are even more likely to die than humans.

Scientists now believe that bats are the natural reservoir for the virus, and that apes and humans catch it from eating food that bats have drooled or defecated on, or by coming in contact with surfaces covered in infected bat droppings and then touching their eyes or mouths.

The current outbreak seems to have started in a village near Guéckédou, Guinea, where bat hunting is common, according to Doctors Without Borders.

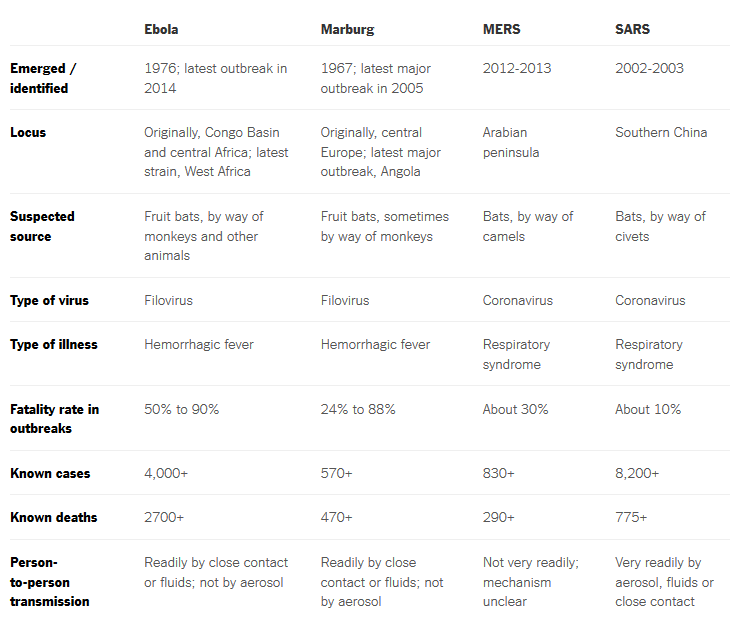

How does Ebola compare with other infectious diseases in the news?

The biggest headlines have tended to involve outbreaks of deadly viruses that medical workers have few, if any, tools to combat. The four most prominent are compared below. No cure is known for any of them, nor has any vaccine yet been approved for human use.

This thing is spreading ooo abi!