[quote_box_right]France views Pan-Africanism as a threat to Western Interests in Africa in General and French Interests in Particular. ~ A French Defense Report, October 2012 [/quote_box_right]

Undoubtedly, Nkrumahism has achieved more for Ghana in particular and Africa in general than any single philosophy in Africa’s entire political history. Prof. Paul Lee was right when he wrote: In the 20th century, probably no one except Marcus Garvey did more to bring freedom and dignity to black people worldwide than Kwame Nkrumah. This statement is a candid reflection of the facts of history. There is no statement truer than Prof. Lee’s in Africa’s entire political history.

Thus, it may appear the Confederate detractors of Nkrumahism are not familiar with the trends and facts of human history, power relations, cause and effect, economic imperialism, scientific racism, colonialism, world-systems and dependency theories, regime theory, and neocolonialism. And so on. Evidently the tendency of analysis gravitates toward easy, tendentious, and simplistic rendition of the facts of history.

We shall use the following series to make the case that, the challenges Nkrumahism faced and still continues to face today do not invalidate it, far from it, since such a contention, after all, is not rooted in the facts of history or of contemporary actualities.

The proper way to look at the optimal benefits of Nkrumahism is, perhaps, to consider the complex dynamics of two football teams at play. The outcome of that match will invariably depend on an array of interacting variable including, but not limited to, the physical and psychological health of the players; referee bias or otherwise; enhanced spectator support; incentivization and player professionalism; team preparation; team’s strategic philosophy; optimal player collaboration; location of play; weather; coach’s strategies and tactics; inevitable mistakes, and their corresponding responses and attributes from the opposing team, among other variables.

It means the aggregate calculations of one team are invariably contingent upon the aggregate calculations of the opposing team, however indeterministic some of the variables involved in a specific gamesmanship are and their corresponding impactful glosses on the decisional covariates of the totality of player interaction and motivational coordination, and other unforeseen and unforeseeable responses as the match goes into motion.

It also means, in effect, that interactive team decisions are not made in a vacuum and are thus executed through player consensus, compromises, and consultations, whether telepathic or empirical. Team decisions are exemplified by gestures, visual signals, tactics and strategies, and other body language or physical manifestations, subtle or not so subtle.

These propositions fundamentally make for the calculating tendency of game theory. How then could it be the fault of the team owner, coach, or team manager when team members take bribes from an opposing team and lose a match on that account? Namely, how bridgeable is the psycho-logical quantum of a Confederate federalist Nkrumah basher who alleges a core group of African leaders appropriated Nkrumah’s ideas, and still, without proffering convincingly verifiable and coherent evidence, hasten to generalize that Nkrumah’s progressive ideas backfired? How reconcilable is this gaping contrast?

Accordingly, the acceptance or rejection of Nkrumahism should be weighed against the totality of a given set of verifiable yet complex facts of history and contemporary actualities. These verifiable facts may, if we can add, be of the nature of unmediated interest or of a compounding variable in the analytic reckoning of the investigator (s). Equally important, the terms of any such valuation must be clearly defined both scientifically and objectively.

The more important point, perhaps, is to push for an assessment of a dress of verifiable facts that directly goes beyond the normative parameters of the scientific conceptualization of Nkrumahism, through its geopolitical fenestration across the moral landscape of political Africa, then to its matchless height of logical conclusion based on a discursive assertiveness of philosophic and political essentialization. Yet the analytic contours may not necessarily follow that specific order or progression!

What is the point? The subtext of our argumentation points to the practical exigencies of contextual rigor which the investigator must pursue across the questioning plane of comparative methodology. We are not making a literal reference to the narrative of opportunistic interventionism vis-à-vis the conceptual complexity of telepathic prostitution where, say, a central idea manages to worm its way simultaneously to the control panels of a collectivity of individuals via the medium of paranormal coercion.

Neither are we preoccupied with the psychosociology of groupthink. On the other hand, we unreservedly concur that tutelage or mentorship enjoys its own natural wavelength of psychosocial existence in the complex scheme of human psychology. Our contention is, in all, one that critiques the social psychology of influence, coercion, free will, and acceptation of ideas.

Where are all these seemingly discursive discourses leading?

In other words, what should we expect of the leaders of France’s former African colonies (Francophone Africa) when the French literally taught African children in the colonies that they descended from the Gauls? Is it any wonder that Jean-Bedel Bokassa, late President of the Central African Republic (CAR), did look up to Napoleon Bonaparte, not Kwame Nkrumah, for philosophical, political, and ideological inspiration?

The French colonial theories of Association and Assimilation reinforced the false equality the metropole placed between itself and the colony, thus making Africans look like confused Black Frenchmen, the same way that an anonymous writer called J.B. Danquah and his leadership colleagues in the UGCC Black Englishmen.

Emperor Bokassa probably spent more than twenty-two million dollars on his coronation when he officially declared himself emperor. In fact, Riccardio Orizio in his essay Dear Tyrant informs us: The money had gone towards ceremonial dress for thousands of guests, A THRONE IN THE FORM OF A NAPOLEONIC EAGLE. Orizio’s essay goes on to elaborate on Emperor Bokassa’s infatuation for Napoleon Bonaparte and for that reason emulated him by putting himself in the mold of Napoleonic personification! Emperor Bokassa shared his peculiar existence with the portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The French took up the bill for Bokassa’s extravagant coronation, allegedly according to Emperor Bokassa himself, a bill to the tune of twenty-two million dollars. What exactly was Emperor Bokassa doing for the French in exchange for the French picking up his coronation bill? Certainly something has gone amiss here, since this little postcolonial narrative does not add up! It also turned out the French had killed Emperor Bokassa’s father when he was six.

The murder of his father happened in his presence, and the reason for his father’s murder was that he had resisted French colonization. Emperor Bokassa’s mother committed suicide after his father’s murder. Then he went on to serve France for twenty-two years, fighting in wars on behalf of France. Emperor Bokassa and his Romanian concubine, Empress Catherine, set up a kangaroo court in one of their private palatial abodes where, together, they executed summary trials of their enemies, real and perceived enemies, some of whom were subsequently literally put to death.

To cement his relationship with France’s political leadership, Emperor Bokassa gave the French “unlimited” access to the country’s reserves of uranium during the Cold War, much as Mobutu and Apartheid South Africa allowed America access to their uranium reserves in exchange for America’s protection and support of their regimes. As he did for the Vatican, he did several favors for French leaders, including giving French President Giscard d’Estaing access to virgin girls and the country’s diamonds.

Turned out, d’Estaing had told Emperor Bokassa he needed diamond for his girlfriends and the latter had, accordingly, granted him privileged access. Surprisingly or not so surprisingly, the d’Estaing Administration and its local collaborators would orchestrate Emperor Bokassa’s overthrew.

But then again, with the aid of the same French political leadership whom he had unconditionally supported and served while in political office he was secreted into the Ivory Coast and placed under Houphouet-Boigny’s protective care and there, whiled away part of what became his social life from France’s continued exploitation of the Central African Republic. They even got Emperor Bokassa another woman to marry in the Ivory Coast.

The French neocolonial relationship with the leaders of her former African colonies is such a complex and weird phenomenon! Elsewhere Pope Paul VI baptized him as thirteen apostle. And then the Vatican secretly put him in its employ and made him run errands on behalf of the pontiff, including acting as an unofficial envoy in behalf of the Vatican in conflict resolution matters, where the “sacred” protection of the Vatican’s interests were the primary motivation for his unofficial assignment.

It has also been widely acknowledged, if speculatively, that Omar Bongo had bankrolled the campaigns and presidencies of some leading French political leaders. Some reports finger Jacque Chirac and Nicholas Sarkozy as two recipients of Bongo’s largesse (Angelique Chrisafis’ article Omar Bongo Pocketed Millions In Embezzled Funds, Claims US Cable, The Guardian, Dec. 30, 2010).

A Wikileaks cable also says: “BONGO WAS FRANCE’S ‘FAVORITE PRESIDENT IN AFRICA,’ AND ‘THIS IS CLASSIC FRANCAPHONE.'”

Omar Bongo was also alleged to have paid millions of dollars to Jack Abramoff, perhaps the most influential lobbyist in America’s political history, to help him buy audience time from George W. Bush. Abramoff went on to serve time in prison for a number of high-profile crimes.

At this point we should make it clear that Omar Bongo’s behavior was not unlike the Asante Traditional Rulers who, according to K.A. Busia, contributed financially to the War Fund set up by the British Government, to buy three British warplanes among others, during the Second Imperialists’ War (World War II).

Again, according to Busia, the Chief of Adanse gave £1000.00 toward the third aeroplane that Asanti contributed as its gifts for the prosecution of the war (The Position of the Chief in the Modern Political System of Ashanti). Likewise, Jarle Simerson noted that the Akyem Abuakwa State Council voted unanimously to impose a special levy on cocoa revenue as part of the Akyem Abuakwa State’s own contribution toward the War Fund set up for the Second World War (see Commoners, Chiefs and Colonial Government: Trondheim British Policy And Local Policies in Akim Abuakwa, Ghana, Under Colonial Rule”).

Those funds were specifically earmarked for the defrayment of expenses incurred, as an Akyem Abuakwa contingent joined the British Volunteer Royal Force, as its contribution to the war effort at a point when East Africa was under Britain’s military occupation.

These Nkrumah bashers and their ideological descendants are quick to criticize Nkrumah for allegedly driving away the British from the Gold Coast, even while they praised Yaa Asantewaa, a woman whose ceremonial leadership would call for the restoration of slavery, as David Owusu-Ansah reminds us in the Historical Dictionary of Ghana.

[quote_box_right]Asante Rebellion, led by Ejusuhemaa, Yaa Asantewa, was organized against the British. On 15th April, Cheif of Asante demanded the return of Prempeh, restoration of the Slave trade, an end to conscript labor, and the expulsion of all foreigners from Kumasi. ~ Historical Dictionary of Ghana. [/quote_box_right]

We are aware that the historicity of Yaa Asantewaa’s leading a war in defense of the restoration of slavery among other demands is a forbidden and anathematic topic, but we have no choice than to restate for the records. It is not in question that it enriches the discourse and adds value to the empirical facts of history.

Evidently, there is some resemblance between Busia’s Aliens Compliance Order and the statement the expulsion of all foreigners from Kumasi. Notwithstanding, many years later, Paa Grant would summon Danquah and other citizens of the Gold Coast, during which he proposed the formation of an organization to deal with British mistreatment and economic exploitation of locals.

That proposition consequently morphed into the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC). So much for the diversion! Question is: How could any right-thinking people unreservedly choose to self-finance or underwrite their continued their colonization, submission, and domination? These were the same people who argued that Nkrumah could not use part of cocoa revenue to develop the would-be nation-state!

These people of yesteryear and their descendants of today are the same people who turned around to praise America’s vision for her sister-nations, the West, regarding America’s investment in Europe in the form of the so-called Marshall Plan. Even American would extend another version of the Marshall Plan to Asia, which writer Sergei Y. Shenin calls The Marshall Plan for Asia (MPA) (America’s Helping Hand: Paving the Way to Globalization). The prognosticative power and reach of American foreign policy put her in the grip of the future where it saw the rise of Europe and Asia as a potential market for the benefit of its expansionist tendencies.

The excruciating myopia of Ghana’s Confederate federalists and much of African leadership, alas, failed to see the practical wisdom in Nkrumah’s penetrating foresight! In sum, Ghanaian Confederate federalists would rather support the Omar Bongos, the Chiefs of Adanse, the Asante Traditional Rulers, and the Akyem Abuakwa State Councils to self-finance their colonization than support the noble vision of Nkrumah effective and proper use of Ghana’s resources to develop Ghana and to get the rest of Africa still under colonialism out of the shackles of colonialism-induced underdevelopment.

What is Francafrique? The term describes the neocolonial relationship between France and her former African colonies. The word, its underlying philosophy and origination, has widely been attributed to Felix Houphouet-Boigny, who originally coined it as France-Afrique. Others, nevertheless, have ascribed the word’s conceptual origination to Francois-Xavier Verschave, one of the fiercest critics of Francafrique, who de-hyphenated the word’s orthographic ancestor as per Houphouet-Boigny’s primordial coinage.

To wit, we owe the word’s present de-hyphenated orthographic character to Verschave’s blending. Perhaps Verschale’s two books Noir Silence: Qui Arretera La Francafrique and La Francafrique: Le Plus Long Scandale De La Republique provide the sharpest critique yet of the policy, as well as of some French political leaders and their African political androids who are united around the political marriage of Francafrique (Mongo Beti’s Main Basse Sur Le Cameroun: Autopsie D’Une Decolonisation).

Technically, the strategy of policy direction and theoretical underpinnings of Francafrique, as well its praxis of political execution, are given serious attention in no less an important text than Bruno Charbonneau’s France and the New Imperialism: Security Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. No doubt the philosophical basis of Francafrique is one of a dependency strategy, or dependency complex if we can appropriate Fanon’s descriptive phraseology.

But Charbonneau is of the opinion that, Francafrique subverts the political freedoms of France’s former colonies and therefore how the subversion of political freedoms, in turn, contributes to instability and to its cognate of underdevelopment. Charbonneau essentially sees Francafrique as an Orwellian algorithm designed to underwrite France’s former colonies’ continued subordination, paternalistic manipulation, dependency, and domination.

The strategy is similar to the Asantes and Akyems who underwrote their own racial indignation by financially supporting their subjugation, via their active collaboration with and self-perpetuation of the colonial enterprise itself, until Nkrumah arrived on the scene to pay for their manumission with his vision, self-sacrifice and political sophistication.

The vortex of Francafrique was the kind of perpetually-revolving trap that Houphouet-Boigny and other leaders from France’s former colonies forcibly drove their people into. Let us state with no pretense at ambiguity that Francafrique was essentially Charles de Gaulle’s brainchild (with Jacques Foccart and Georges Pompidou).

Thus, Houphouet-Boigny was fundamentally a Gaullist and not an Nkrumahist. In this connection, it is important we stress that Omar Bongo, Emperor Bokassa, Houphouet-Boigny, etc., had French technocrats as their top-level advisers: Security, economic, and political. What is more, Houphouet-Boigny and Omar Bongo, to mention but two, had French mercenary soldiers who protected them.

At one point, in 1963, for instance, Houphouet-Boigny and his inner circle framed up a number of prominent citizens of the Ivory Coast and either had them detained or put under house arrest. Included in the swoop were Members of Parliament, Ministers of State, and the Presidents of the Supreme Court and the National Assembly. For one thing, the President of the Supreme Court died while in detention awaiting his trial, just like Danquah. Houphouet-Boigny, in due time, conceded there never was any coup against him. Rather he blamed Henry Goba, his then-deceased Chief of Internal Security, for misleading and misinforming him.

De Gaulle vehemently rejected Quebec’s forced absorption into the Canadian federation in the same way as he rejected Biafra’s continued attachment to the Nigerian federation. Yet, De Gaulle resisted Basque secessionism from Southwestern France, in any event refusing to apply the same logic he fabricated to justify Ibo-dominated Biafra from seceding from Nigeria, to the Basque question. He also advanced European integration but in the general context of France’s strategic interests and historical, cultural prestige.

Orwellian doublespeak and Machiavellianism assumed the forked tongue of France’s Gaullist foreign policy.

Perhaps, it is not surprising then when Houphouet-Boigny likewise supported Biafran secessionism, even as Wole Soyinka resisted the breakaway, while he [Houphouet-Boigny] brutally crushed the secessionist tendencies of the Sanwi People from the Southeast region of the Ivory Coast, somewhat similar to De Gaulle’s strategic rejection of Basque secessionism from Southwestern France.

What is more, both Houphouet-Boigny and De Gaulle supported the secession of Katanga from the Republic of the Congo. The similarities do not end there, however. France under De Gaulle opposed African federation and Pan-Africanism, just as Houphouet-Boigny, under France’s close watch, instigation and intelligence manipulation, worked behind the scenes to frustrate Nkrumah’s unitary continentalization of Africa’s strategic interests and Pan-Africanism.

The fact is, there were and are certain African scholars and commentators who had, and continue, to castigate those African leader who, indeed, had identified the praxis of the one-party political system with a historical and cultural conceptualization of the unitary state, but this time they had no words to describe how they felt when Biafra chose the easy path of secessionism.

Surely that betrayal of Biafran geopolitical detour from the Nigerian federation has come to haunt Soyinka’s moral psychology for all the combinations and permutations of good and bad reasons. Houphouet-Boigny opted out of the federation which France under De Gaulle’s leadership had offered her former African colonies.

France’s federation strategy was, basically, designed to bring her former colonies under one umbrella in order to effectualize her monopolistic exploitation of those colonies and to protect their unitary balkanization against undue radical influences from Anglophone Africa. In the end, however, Houphouet-Boigny endorsed Biafra’s secessionist proposition because his French mentors and patrons, led by De Gaulle, had endorsed it.

This should come as no surprise to the political novice. It was and still is expected of African leadership androids in the Francafrique dragnet to behave accordingly.

Elsewhere, it has widely been speculated that Houphouet-Boigny had a hand in Nkrumah’s overthrow and was also among a small group of anti-Nkrumah African leaders that lobbied against America’s support for the Akosombo Dam.

It is the case that though Nkrumah had mentioned America, Britain, West Germany, and Israel as the major forces behind his overthrow, to his British friend Geoffrey Bing, Ghana’s Attorney General, from 1957 to 1961, others have pointed the finger at France. Some point to French complicity as fact and not merely conjecture or speculation.

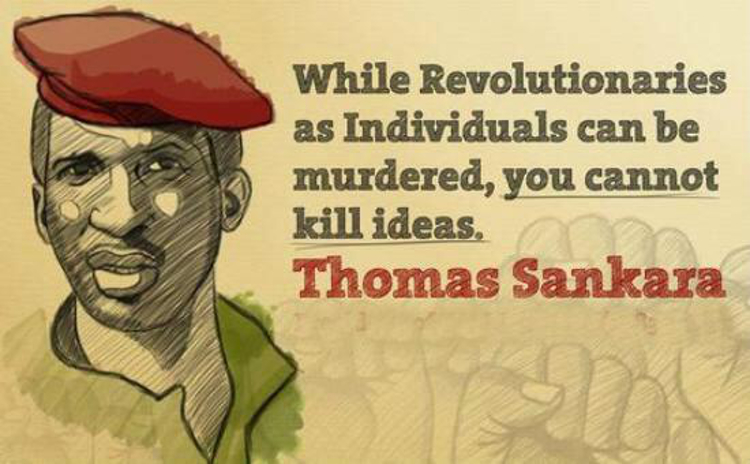

The justification for the French complicity has derived mostly from France’s distaste for Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanist foreign policy, continental unification project, Guinea’s political fraternization with Ghana, and Nkrumah’s support for the African Revolution. Other scholars have also speculated that France and Houphouet-Boigny may have had a hand in Thomas Sankara’s assassination as the focus of the his domestic and international politics and Burkina Faso’s political economy gradually shifted towards a Pan-Africanist fraternization with other African sister-nations like Ghana.

Houphouet-Boigny has also been implicated in his support for the UN’s intervention in the Congo Crisis that led to Patrice Lumumba’s death, French mercenary Bob Denard’s coup against Benin’s Mathieu Kerekou, and so on (see the African Agenda article already referenced). It clearly explains why some Ivorians are disgusted at the UN’s so-called the Felix-Houphouet-Boigny Peace Prize and why they are advocating its revocation.

In the meantime, corrupt pro-French hangers-on in the Sankara Government, like Blaise Compaore, could not stand the disciplinary injunctions Sankara embarked upon to stem corruption and the socialist reconfiguration of Burkina Faso’s political economy which Sankara initiated. Therefore, Compaore joined up with reactionary forces from without and within to get him out of the way.

We cannot rule out the fact that, overall, the socialist orientation of Sankara’s politics, the nationalization of his country’s political economy if you will, posed a serious threaten to France’s underhanded monopolistic re-colonization of her former colony (see also Pierre Englebert’s “Burkina Faso: Unsteady Statehood in West Africa”). But Houphouet-Boigny never objected to the socialist policies of French leaders like Francois Mitterrand.

The French did not object to Mitterrand’s socialist policies either. We may have to add that the French have never forgiven Paul Kagame for his betrayal as seen in his strategic shift of national allegiance from France to the Anglophone world, America and Britain specifically, even to the point of Anglicizing Rwanda’s official languages and institutions!

Fortunately or unfortunately, depending on where the focus is, the support Kagame gets from Britain and America has tended to neutralize any French underhanded attempts to make his government unpopular and cause Rwandans to replace him with a puppet regime who will respond to the tenets of Francafrique.

But the Kagame Government is a puppet regime notwithstanding. The only difference is that the focus of allegiance has shifted from one end of the postcolonial or neocolonial dilemma to the other end.

In conclusion, we make the case that Francafrique probably represents the most dangerous impediment to African unity and her collective freedom to act in the interest of her strategic priorities, civilization, growth and development.

Why does the West view Pan-Africanism as an existential threat?

The moral paradox which may have confronted Houphouet-Boigny at the height of French imperialism in Africa was that his top-level French advisors, among which we can authoritatively mention De Gaulle, Jacques Foccart, Bob Denard, and Georges Pompidou, persuaded him to resist Pan-Africanism and African unification, while they endorsed European integration, values, and Pan-Europeanism.

Even some European countries and leaders have come out strongly against Francaqfrique, advising and persuading the political leadership of France to revise that policy, or scrape it. Former French President Jacques Chirac was bold enough to admit that France’s existence, survival, and power owes much to the flow of African money, mostly from her former African colonies, into France. Ex-President Chirac succinctly described his frank admission as “L’ARGENT DE L’AFRIQUE.”

The facts also make it clear that the political ideology of Francafique, if we may add, was Houphouet-Boigny’s greatest bequest to Africa! No wonder political and social activists, political scientists, scholars, writers, researchers, policy makers, and ordinary citizens of France’s former African colonies are resisting Francafrique and, instead, variously agitating for Nkrumahism in its stead!

Dr. Cheikh Tidiane Gadio, a Senegalese diplomat and ex-Minister of Foreign Affairs, is one such intellectual and politician leading the fight for Nkrumahism in that part of the Francophone African belt. We should state it for the records that we had the opportunity to meet Dr. Gadio in Dr. Molefi Kete Asante’s home where we engaged him on his Nkrumahist and Pan-Africanist vision for Africa. Like we said a while ago, Dr. Dadio’s exemplary leadership in defense and spread of Nkrumahism is being replicated across the former French African colonies!

Most important, this caliber of progressive intellectuals and the governments they work(ed) with are finding it more and more difficult to identify with Francafrique! Rather, they see Nkrumahism and Pan-Africanism as a practical response to Africa’s survival in the 21st century. This is where their intellectual and visionary investments are leading them. In effect, Nkrumahism is just as alive as the unitary state of Ghana, post-Apartheid South Africa, decolonized Africa, and the improved state of North-South and intra-continental African relations.

Pan-Africanism as an idea alone I feel could have saved Africa from the bottomless it suffers right now. Nkrumah alone could have made this great continent great again. But for a few bastards – UGCC, Danquah-Busia tradition and so on!

Thanks for telling the truth on Yaa Asantewaa!

Why not revive Pan-Africanism? Why are you waiting and procrastinating? Remember, ideas like Nkrumah’s are not going to go down the throats of African’s as easily as good as they sound. These ideas will be peppered on by sillies, idiots, non-patriots, irresponsibles etc. before it touches the lips of its supporters. Your job is to prevent that from happening!

Great essay. I would like a version of this in more simple English. I get the import. But if Nkrumahism must be revived for the good of all, it needs to be translated in digestible language. This author is erudite, no doubt. My concern is more a pragmatic one – how do we push these complex ideas to the masses?