DALLAS — Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital has finally released the medical records of Thomas Eric Duncan, who has become the first and still the only person to have died of the Ebola virus in the U.S., to his family, which has raised new questions about the treatment he received when he first sought care at the hospital.

Thomas Eric Duncan, 42, had a high fever — his temperature was 103 degrees — during his four-hour visit to the emergency room of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on Sept. 25, according to 1,400 pages of medical records that Mr. Duncan’s family provided to the press. Mr. Duncan also reported severe pain, rating it an eight out of ten. His electronic medical record shows the fever Mr. Duncan suffered was marked with an exclamation point.

But the hospital sent Mr. Duncan home, even after learning that he had recently arrived from Liberia. He was prescribed antibiotics and was told to take Tylenol, returned to the apartment where he was staying with his fiancée and three other people. He was back at the emergency room on Sept. 28 and was immediately placed in isolation in the hospital. He died of Ebola on Wednesday, the only person to die from the disease in the United States.

The reported details about his condition contradicted the hospital’s previous description of Mr. Duncan’s first visit. Hospital officials had said that Mr. Duncan had a temperature of 100.1 degrees and that his symptoms “were not severe at the time he first visited the hospital emergency department.”

On Friday, Wendell Watson, a spokesman for Texas Health Resources, the organization that oversees the hospital, said in a statement that it continued to “closely review and evaluate the chain of events related to the first Ebola virus diagnosis in the United States.” But the statement did not directly address Mr. Duncan’s 103-degree fever which contradicts the hospital’s initial claims that he had had a lower temperature of 100.1.

Mr. Watson said the hospital had “made changes to our intake process as well as other procedures to better screen for all critical indicators of Ebola virus.” He added, “We are committed to providing the best possible care to every patient we see, and to sharing our experiences and learnings in managing this insidious disease with the broader health care community.”

Included in the records, according to The Associated Press, was an emergency room physician’s note dated Sept. 26 that said Mr. Duncan was “negative for fever and chills.” The note read: “I have given patient instructions regarding their diagnosis, expectations for the next couple of days, and specific return precautions. The condition of the patient at this time is stable.”

Mr. Duncan’s brother, Wilfred Smallwood, who lives in Phoenix, said he had not seen the records. But told what they showed about Mr. Duncan’s fever, he said it reinforced the family’s belief that Mr. Duncan’s case was not handled competently and that Mr. Duncan should not be held accountable for the nationwide health scare.

“I’m not a medical professional, but I think it’s clear to the public that he went to the hospital the first time and was turned away and told, ‘You’re O.K.,’ ” Mr. Smallwood said. “Who do you blame for it happening now? One hundred and three, they said go home. Now he’s dead. Who do you blame for this?”

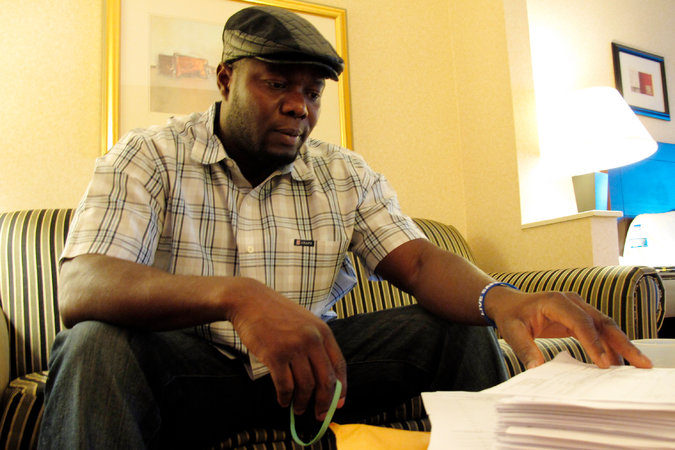

Mr. Duncan’s nephew, Josephus Weeks, who provided the records to The A.P., said on CNN on Friday that his uncle would have received better treatment by the hospital had he been white. “They treated him the way they did because of the color of his skin,” Mr. Weeks said.

Mr. Weeks said he had requested that the hospital take certain steps to help Mr. Duncan survive, including having him transferred to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta and giving him blood transfusions, but he said he was turned down.

As the family continued to grieve, Saymendy Lloyd, an activist who identified herself as a spokeswoman for Mr. Duncan’s fiancée, Louise Troh, said Mr. Duncan was unaware that he had Ebola when he left Liberia for the United States. Mr. Duncan helped take a pregnant woman to and from a hospital in Monrovia, the Liberian capital, in the days before he flew to America. The woman died of Ebola, as have others who came into contact with her.

“Not even her family members knew” she had Ebola, Ms. Lloyd said at a news conference in Washington. “She had no symptoms at all of Ebola. She had pregnancy symptoms.”

Ms. Lloyd also said Ms. Troh’s and Mr. Duncan’s son, Karsiah, a student at Angelo State University in San Angelo, Tex., has not been allowed back at school because of concerns about the virus. But Becky Brackin, a spokeswoman for the university, denied Ms. Lloyd’s claim.

“Karsiah is welcome back on this campus at any time,” Ms. Brackin said.

The hospital has made contradictory and inaccurate statements in recent days. It apparently provided the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its own administrators with the wrong date of Mr. Duncan’s first appearance at the hospital, originally saying it was Sept. 26, but later saying it was Sept. 25. One of the hospital’s news releases included the wrong date of Mr. Duncan’s diagnosis, which was confirmed on Sept. 30 but was noted as Sept. 29 in the statement. And the hospital placed some of the blame about why Mr. Duncan was sent home after his first visit on a problem with its electronic records system, but it later said the system had operated correctly.

These conflicting communications, as well as the medical records, have intensified the uncertainty over why the hospital did not view Mr. Duncan as a potential Ebola case during his first visit to its emergency room.

Mr. Duncan first went to Texas Health Presbyterian after 10 p.m. on Sept. 25. In a statement it issued on Oct. 2, the hospital said he had a temperature of 100.1 degrees and had reported having abdominal pain, a headache and decreased urination. “These symptoms could be associated with many communicable diseases, as well as many other types of illness,” the hospital said.

The nurses claim that “Mr. Duncan was asked if he had been around anyone who had been ill, and told them he had not,” the hospital said. But they confirmed he told nurses, when asked if he had traveled outside the United States in the last four weeks, that he had been in Liberia, where Ebola has been prevalent.

The hospital had said there had been a flaw in its electronic records system and suggested that while the nurses may have had access to the information about his travel history, the doctor who treated Mr. Duncan had not. But the hospital later retracted that claim, explaining that there was no flaw in the system and the physician could indeed view information about Mr. Duncan’s travels from Africa.

Initially, Dr. Mark Lester, executive vice president of Texas Health Resources, told reporters that information about Mr. Duncan’s travel history was not “fully communicated” to the full medical team. Mr. Duncan was sent home because the diagnostic team believed he simply had a low-grade fever from a viral infection, Dr. Lester had said.

But the newly released medical records and the hospital’s statement acknowledging there was no flaw in the records system makes it unclear why the doctor sent him home.

Perhaps could it be an issue with Mr. Duncan’s health insurance, if he had any, or yet, could it be because he was black?