According to the title of one Eurocentric biography of David Livingstone, he was “Africa’s Greatest Missionary”. He hailed from the County of Lanark in the central lowlands of Scotland.

This is both interesting and false given that the Lanarkshire-born man, considering that estimates of the number of people he converted in the course of his 30-year career vary between one and none, and in only a part of Africa, Southern Africa!

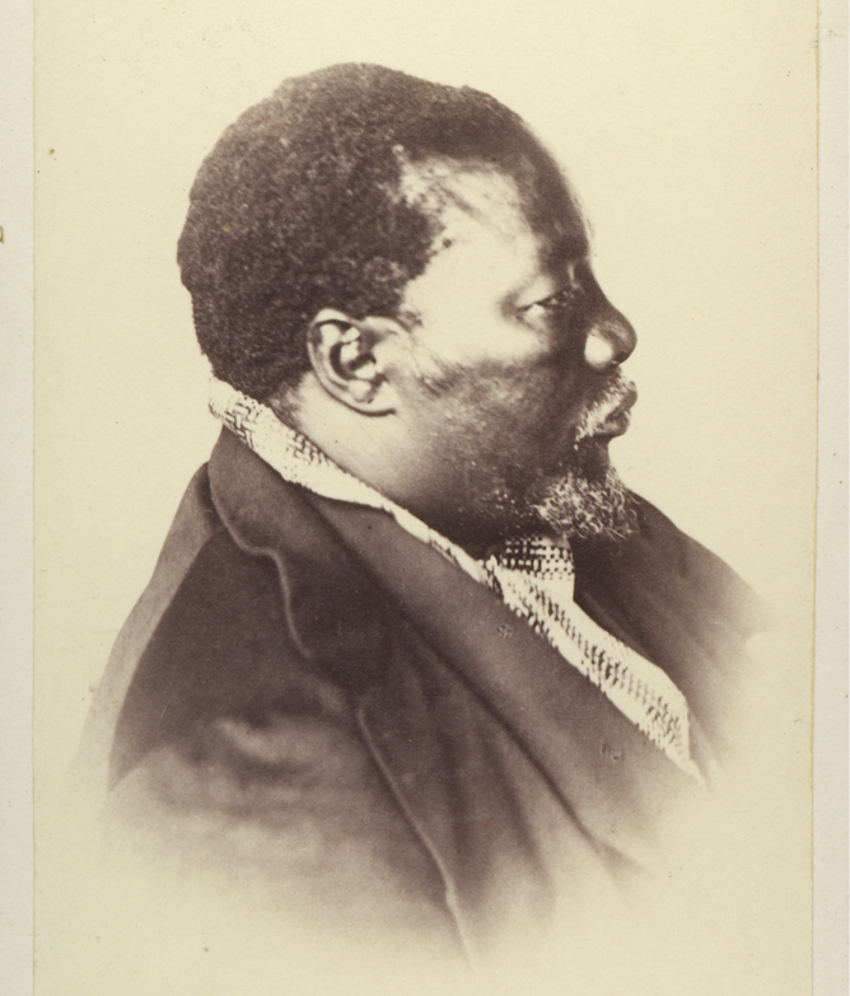

In the estimation of Neil Parsons, of the University of Botswana, Chief Sechele, who was Kgosi of the Bakwena State, then part of the Tswana Kingdom, in what is now Botswana, was Southern Africa’s Greatest Modern Christian Missionary.

Chief Sechele “did more to propagate Christianity in nineteenth-century southern Africa than virtually any single European missionary can ever claim”.

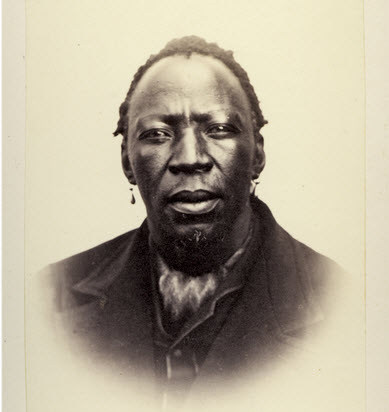

And for European missionaries who vied and competed for African souls in more ways than for Christ’s sake, Chief Sechele was a frustrating puzzle. They described him to their European monarchs as “a half Christian and a half heathen”.

Which from the 15th century on was not very surprising since everything Europeans saw in Africa was half man – half savage, half animal – half human, half good – half heathen. Every single African Religion or religious practice was animist or heathen.

Europeans strongly objected to his use of African traditional charms and purification rites and rituals, and the list of his ancestors on the church walls of his temples.

And yet, even the ones who most hated Chief Sechele admitted, “he reads the Bible threadbare”, and when confronted he ran scriptural rings around them.

“Roger had to keep his wits about him,” wrote the missionary Elizabeth Price about her husband, “or he would have been lost, so wily and cunning is Sechele – murdering sacred scripture and bringing it to defend him in a way which horrifies and amazes one. A strange, strange mixture he is.”

Born in 1812, he was 10 when his father, the previous Kgosi, was killed. Two of his uncles divided the ethnic group between them. Sechele escaped with a few followers for nine years, and returned to oust one of his uncles.

This was how things stood when Chief Sechele first met Livingstone – he ruled over half of the state.

Chief Sechele amused Livingstone by asking for medicine to make him a better hunter. But the thing Sechele wanted above all from Livingstone was literacy.

He learned the alphabet, upper and lower case, in two days, compiled his own spelling books, and set about reading the one book in the Tswana language, the Bible. He ate breakfast before sunrise in order to start school as quickly as possible, and then taught his wives to read.

As Sechele grew increasingly interested in Christianity, he found two huge barriers in his way. One was rain.

The Tswana people had rainmakers, whose job was to use Voodoo to make the rain come. Livingstone, like all missionaries, vehemently opposed rainmaking, on both religious and so-called scientific grounds.

The greater problem was polygamy. Chief Sechele had five wives, and Livingstone’s Christinity insisted that he get rid of the “superfluous” ones. This was a political as well a personal nightmare, threatening the political structure of the state and relations with other ethnic groups, since some of his marriages were more so political ties with his allies than traditional marriages.

But Chief Sechele, who happened to be his tribe’s rainmaker as well as Kgosi, returned to rainmaking, considering it a political necessity, and late in life returned to polygamy, marrying a young woman for what do not seem to have been entirely political reasons.

Chief Sechele was an intelligent and insightful Christian who quickly realized that Eurocentric Christianity, as it had popularly become branded, had no basis in Christian doctrine: not as a spiritual walk, not as religion and certainly not as a philosophical encumbrance. That, in the humble foundations of Christianity itself lay the intrinsic spirituality and religious rites and rituals of African Thought.

Sechele was cognizant of the measure of African influence, to say the least, on Christ Himself and argued with European missionaries that Christ was given up for crucifixion because His African religious ways were in stark contrast with the Hebrew.

“Christ’s all-forgiving God was not the same kind of God you read about in the Old testament,” Sechele would insist. His God was African and for that he was crucified.

Chief Sechele’s ‘strange mixture’ was in fact African Christianity. Unlike other converts who were content to follow European Christianity, Sechele went back to the source and recreated it as an indigenous African religion.

He threw away the European depiction of Christ, white with long straight hair, and carved a statue, with profuse African features, and long twisted braids to boot, as Jesus Christ!

Hopefully, in the year of the so-called Livingstone bicentennial, Africans the world over will finally replace him and give Chief Sechele the recognition due him.

In time, he will be regarded as one of Africa’s most foremost modern Christian Theologians.