DALLAS — The murderous civil war that terrorized Liberia from 1989 to 2003 left at least 5 percent of the population dead, and sent wave after wave of refugees to neighboring countries. To escape the ethnic and political turmoil, more than 700,000 fled from a nation that had barely two million residents when the conflict began.

Among them were Thomas Eric Duncan, the man who brought the Ebola virus to the United States last week, and Louise Troh, the woman he had come to Dallas to visit. After meeting in the early 1990s in a refugee encampment near the Ivory Coast border town of Danané, the two Liberians started a relationship and bore a son, several family members said.

It is not clear what drove the couple apart — Mr. Duncan, 42, who is fighting for his life at a Dallas hospital, has not spoken publicly, and Ms. Troh, 54, who will be quarantined for another two weeks, declined to discuss their history.

But starting in 1998, when Ms. Troh left for the United States — first settling in Boston, and then in Dallas with another Liberian man — they began a 16-year separation.

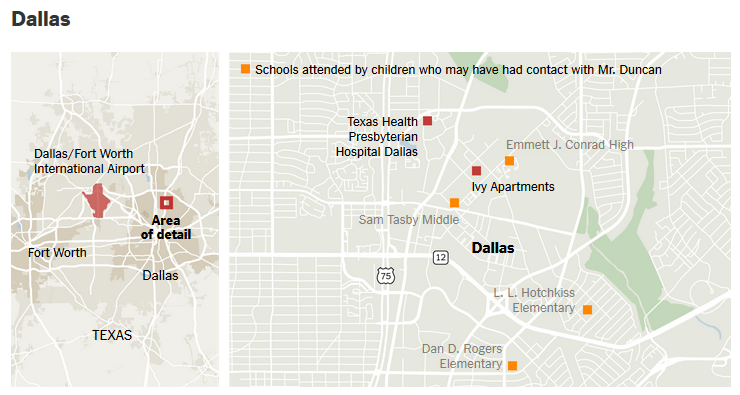

Not only did Mr. Duncan not see Ms. Troh, he missed the entire childhood of their son, Karsiah, who adapted well enough to his new home to become the starting quarterback for the Conrad High Chargers.

Tragedy befell Ms. Troh in February when a daughter in Liberia died during childbirth. In March, she split with Peterson Wayne, the Liberian refugee she had followed to Texas. It was after that that she and Mr. Duncan apparently revived their relationship, first at long distance, and then when Mr. Duncan landed at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport on Sept. 20.

“They had had a falling out, and had patched things up,” said the Rev. George Mason, Ms. Troh’s pastor at Wilshire Baptist Church, “and he had come here with the intention to marry and start a new life together. Obviously, what happened has thrown a wrinkle into that.”

And then some. What began as a joyful reunion — refugees from African civil strife seeking to rebuild their lives in America — spiraled last week into a national health scare once only imagined in science fiction. Once again, Mr. Duncan and Ms. Troh found themselves in the vortex of larger forces beyond their control.

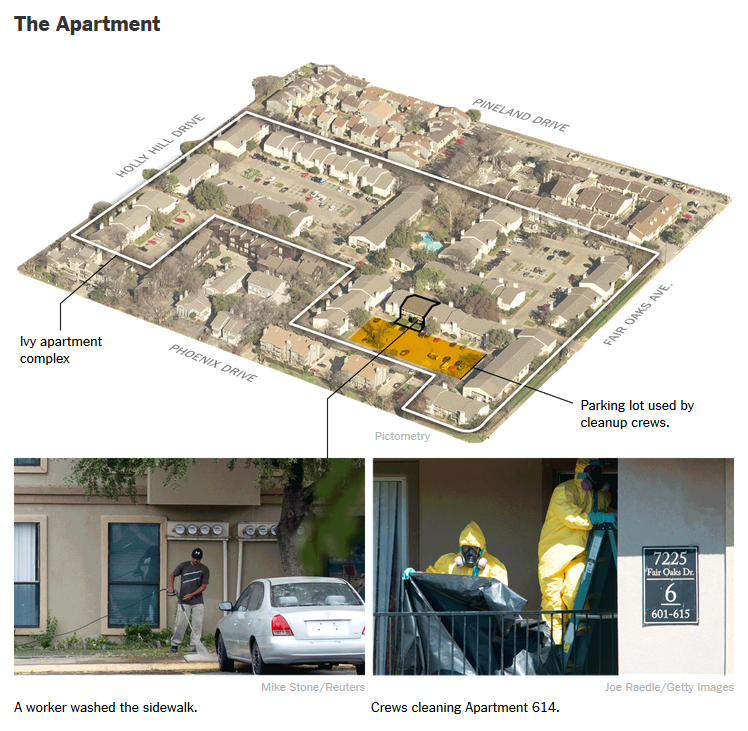

The arrival of Ebola with Mr. Duncan put Dallas so on edge that parents kept children home from school and officials with the State Fair of Texas programmed Big Tex, their talking mechanical mascot, to urge fairgoers to wash their hands. It commanded the attention of President Obama and his top health advisers, exposed a series of disconcerting lapses in medical care and crisis logistics and incited a national debate over whether to restrict travel to and from afflicted countries. For Ms. Troh, who spent five days as a captive in her contaminated apartment, a week that started with home-cooked meals and happy introductions ended with the seizure of her belongings by workers in yellow hazardous-material suits.

On Sunday, the director of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, said that Mr. Duncan’s medical condition was quite critical and that he was “fighting for his life.”

Mr. Duncan, who goes by Eric, is the youngest of seven siblings, according to his brother, Wilfred Smallwood, who lives in Phoenix. His father was an engineer for an American mining company, Mr. Smallwood said.

After five years in the refugee camp in French-speaking Ivory Coast, the family moved to Ghana, where there was less of a language barrier, Mr. Smallwood said. A sister, who now lives in Charlotte, N.C., was the first of the clan to make it to the United States, shortly after the war began. Their mother came a decade later, followed by Mr. Smallwood, but Mr. Duncan left Ghana and returned to Liberia, where he stayed.

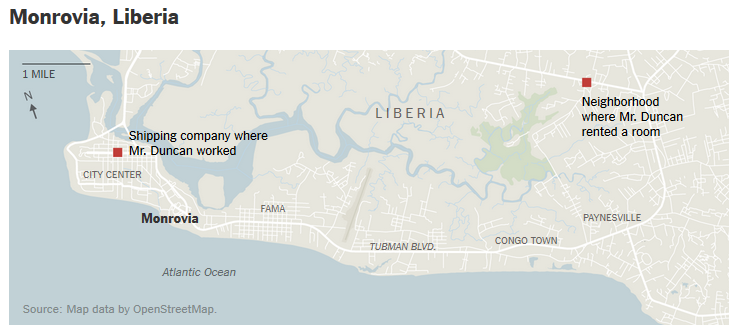

Before leaving for Dallas, Mr. Duncan had been living in a neighborhood called 72nd SKD Boulevard on the eastern outskirts of Monrovia, an hour’s commute from his job in the central city. He had worked for about a year as a driver for Safeway Cargo, which acts as the customs clearance agent for FedEx in Liberia, said Henry Brunson, the company’s manager.

Mr. Duncan rented one of three small rooms in a one-story white building with concrete walls and a roof of corrugated zinc. He enjoyed riding his Yamaha motorcycle, and interacted regularly with his neighbors but did not receive guests at home.

Mr. Smallwood said Mr. Duncan obtained a visa several weeks before leaving, and on Sept. 4 he quit his job without warning or explanation, Mr. Brunson said.

But 11 days later, only four days before his scheduled departure, Mr. Duncan made a consequential decision to help his landlords transport their pregnant 19-year-old daughter to a hospital, according to the landlords and other neighbors. The woman, Marthalene Williams, had been stricken with Ebola and was convulsing.

He rode in a taxi with the woman and her relatives. After the hospital turned her away for lack of space in its Ebola ward, he helped carry Ms. Williams, who was too weak to walk, from the taxi back into her house. A neighbor said she saw Mr. Duncan holding her legs while others supported her back and arms. The woman died several hours later.

On Sept. 19, as he prepared to board a Brussels Airlines flight to the Belgian capital, where he would catch connections to Dulles International Airport and then Dallas, Mr. Duncan was screened for Ebola by health workers at Monrovia’s airport. His temperature measured as normal — 97.3 degrees, according to the C.D.C. When asked on a form whether he had been exposed to anyone with Ebola in the past 21 days, the virus’s maximum incubation period, he answered no, said Binyah Kesselly, chairman of the Liberia Airport Authority.

Texas prosecutors said Sunday that they were considering whether to bring charges against Mr. Duncan.

“We are actively having discussions as to whether or not we need to look into this as it relates to a criminal matter,” Craig Watkins, the district attorney for Dallas County, said Sunday. “We’re working with all the different agencies to get to the bottom of it.” Mr. Watkins did not elaborate on what those charges might be.

It was Mr. Duncan’s first trip to the United States, his brother said, and he was clearly excited to reunite with Ms. Troh and his long-lost son, who now attends Angelo State University, west of Dallas.

Mr. Duncan settled into Ms. Troh’s sparsely furnished two-bedroom apartment, Unit 614, on the second floor of the Ivy, an unremarkable complex in the Vickery Meadow neighborhood. A king-size bed filled Ms. Troh’s room, and two mattresses covered the blue-carpeted floor of the living room, which was dominated by a large-screen television. The apartment was shared by Ms. Troh’s 13-year-old son, Timothy Wayne, and two men in their 20s — Mr. Smallwood’s son, Oliver, and a friend named Jeffrey Cole.

Jet lag sapped Mr. Duncan for several days, and he found himself restless at night and sleepy during the day, said Josephus Weeks, a relative of Mr. Duncan’s in North Carolina. Ms. Troh liked to prepare an excess of food so she could lure others to eat it, according to Peterson Wayne, and she introduced family and friends to Mr. Duncan when they dropped by.

Youngor Jallah, one of Ms. Troh’s daughters, said she met Mr. Duncan when she dropped off her children on Sept. 21 before rushing away to her job as a nurse’s assistant. He seemed nice, she said, and offered condolences about her sister’s death in childbirth last February. When she came back to pick up the children, her 6-year-old daughter, Rose, announced, “Oh, Grandma has a new boyfriend.”

On Sept. 25, Mr. Duncan began complaining to Ms. Troh about chills, and she drove him to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, not far from her apartment. He arrived in the emergency room with a mild fever of 100.1 degrees and reported having abdominal pain for two days, a sharp headache and decreased urination, according to the hospital. When a nurse took his history, the hospital has reported, he said he had not been around anyone ill but had recently been in Africa.

The nurse noted this, but doctors apparently failed to consider the possibility of Ebola for reasons that remain unclear. Mr. Duncan was sent home with antibiotics that were powerless to halt the progression of his virus.

On the morning of Sept. 28, after a nightlong bout with diarrhea, M. Duncan did not want to get out of bed. Ms. Troh, who is also a nurse’s assistant, had to go to work and called Ms. Jallah to come care for him. When she arrived, he complained of being cold, and she took a quick trip to a nearby Walmart to buy a thicker blanket.

She made him tea, and then fetched a blood pressure monitor from her car. The readings were frighteningly low, and his temperature measured close to 103, she said. His eyes had turned red, and he told her he had been to the bathroom seven times during the night. “O.K., you can have your tea, but then we are going to the hospital,” she told him. He resisted, saying he would wait for Ms. Troh to return. She circumvented the argument by calling 911.

Ms. Jallah said she was not thinking specifically about Ebola, but she had a warning for the arriving emergency medical workers: “You need to wear masks and be protective because this man is from a viral country.”

Ms. Jallah followed the ambulance to the hospital, and by the time she found Mr. Duncan in Room 42, nurses had already placed an isolation sign on the door. When she got back to her apartment, she instructed her four children not to touch her, sealed her clothes in a plastic bag and took a bath laced with Clorox.

She called her mother and told her to avoid the bed that Mr. Duncan had shared and to bag up his towels. When Ms. Troh protested because the blanket was new, Ms. Jallah returned to Walmart to buy bedding, towels and a thin mattress. “That blanket is not as important as your life,” she told her mother.

The next day, she and her mother returned to the hospital and could see Mr. Duncan through a glass panel. Ms. Troh gestured to him, asking if he could sit up, and Mr. Duncan shook his head no. She waved and encouraged him to wave back, but he could barely move his hand under the sheets, Ms. Jallah said.

On Tuesday, tests confirmed that Mr. Duncan had contracted Ebola. Ms. Jallah said that she and Ms. Troh learned the news on television that morning. They have been quarantined ever since, the children instructed to stay home from school.

Ms. Troh and the other residents of her unit were moved on Thursday to a comfortable private residence — with a basketball court for her son — that was provided by a local benefactor. She said during a Saturday telephone call that she remained “stressed out” by her concern for her family’s health and by a week spent in the media glare. “We are peaceful people,” she said. “We are not criminals. We are here legally. Leave us alone.”

Ms. Jallah and her family remain in their cramped apartment, which lost power for several days this week after a storm. With two weeks of isolation remaining, the twice-a-day visits from health workers have revealed no symptoms of infection.

By ALAN FEUER OCT. 5, 2014 FOR THE NYT