ATLANTA, Georgia, U.S. – Not that Gandhi has any noteworthy standing in Africa nor do I think his standing among the remnants of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his inspired Civil and Human Rights Movement in the United States is significant to write home about.

Nevertheless, it was in 1950 that Dr. King heard Mordecai Johnson, president of a Historically Black College, Howard University, speak of his recent trip to India and Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance techniques.

King situated Gandhi’s ideas of nonviolent direct action in the larger framework of how African American Christians could fight for their Human and Civil Rights in a Jim Crow America, even declaring that ‘‘Christ showed us the way and Gandhi in India showed it could work’’ (Rowland, 2,500 Here Hail Boycott Leader).

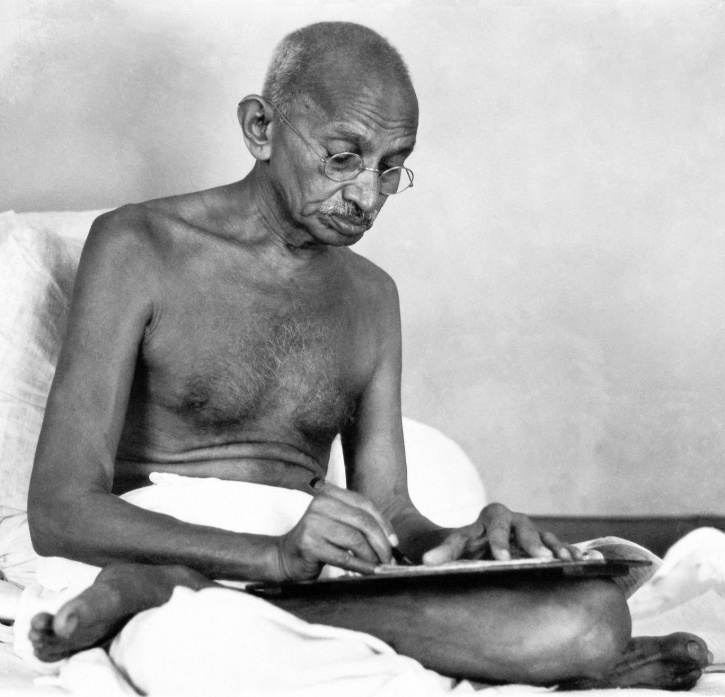

Dr. King wrote in a tribute, marking the tenth anniversary of the assassination of Mohandas Gandhi, in the Hindustan Times, that Gandhi had done more than any other person of history to reveal that social problems can be solved without resorting to ‘primitive methods’ of violence.

In this sense Dr. King positioned the struggle of African Americans against racial segregation in Montgomery, Alabama, and the US at large within a synthesis of Gandhi’s method of non-violence and the professed Christian ethic of ‘love’. King believed that this was the best weapon available to African Americans in their struggle for freedom and human dignity.

But a new book combs through Gandhi’s own writings during his stay in Africa. According to government archives found, this convincing portrait is at variance with how the world, Martin Luther King Jr., and in particular, how Liberals in the US, who funded Dr. King’s approach to fighting for equality under that law, regard Gandhi.

Is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the revered leader of India’s freedom movement, a racist? More directly, did he despise Africans while he lived in South Africa?

This question has been examined by many historians of our period across the continent of Africa. Perhaps, they argue, it is what African leaders found earlier about Gandhi – but couldn’t convince the rest of the world – that forced many African Liberation movements to reject the idea of Peaceful Protests in civil disobedience against Colonial rule in Africa.

Gandhi was born in 1869 and trained as a lawyer in England. He returned to India in 1891 but was unable to find work. In 1893, he accepted a one-year contract to do legal work for an Indian firm in South Africa but remained there for some 21 years.

During his stay in South Africa, Gandhi routinely expressed “disdain for Africans,” says S. Anand, founder of Navayana, the publisher of a new book titled The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire.

According to this book, Gandhi described Africans as “savage,” “raw” and living a life of “indolence and nakedness,” and he campaigned relentlessly to prove to the British rulers that the tiny Indian community in South Africa was superior to native African communities.

Much of the halo that surrounds Gandhi today is a result of clever repackaging, write the authors Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, professors at the University of Johannesburg and the University of KwaZulu Natal.

“As we examined Gandhi’s actions and contemporary writings during his South African stay, and compared these with what he wrote in his autobiography and ‘Satyagraha in South Africa,’ it was apparent that he indulged in some ‘tidying up.’ He was effectively rewriting his own history.”

Here is a sample of what Gandhi said about Africans in South Africa:

* One of the first battles Gandhi fought after coming to South Africa was over the separate entrances for whites and blacks at the Durban post office. Gandhi objected that Indians were “classed with the natives of South Africa,” who he called the kaffirs, and demanded a separate entrance for Indians.

“We felt the indignity too much and … petitioned the authorities to do away with the invidious distinction, and they have now provided three separate entrances for natives, Asiatics and Europeans.”

* In a petition letter in 1895, Gandhi also expressed concern that a lower legal standing for Indians would result in degenerating “so much so that from their civilized habits, they would be degraded to the habits of the aboriginal Natives, and a generation hence, between the progeny of the Indians and the Natives, there will be very little difference in habits, and customs and thought.”

* In an open letter to the Natal Parliament in 1893, Gandhi wrote:

“I venture to point out that both the English and the Indians spring from a common stock, called the Indo-Aryan. … A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.”

* At a speech in Mumbai in 1896, Gandhi said that the Europeans in Natal wished “to degrade us to the level of the raw kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with, and then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

* Protesting the decision of Johannesburg municipal authorities to allow Africans to live alongside Indians, Gandhi wrote in 1904 that the council “must withdraw the Kaffirs from the Location. About this mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians, I must confess I feel most strongly. I think it is very unfair to the Indian population and it is an undue tax on even the proverbial patience of my countrymen.”

* In response to the White League’s agitation against Indian immigration and the proposed importation of Chinese labour, Gandhi wrote in 1903: “We believe also that the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race.”

* Gandhi wrote in 1908 about his prison experience: “We were marched off to a prison intended for Kaffirs. There, our garments were stamped with the letter “N”, which meant that we were being classed with the Natives. We were all prepared for hardships, but not quite for this experience. We could understand not being classed with the whites, but to be placed on the same level with the Natives seemed too much to put up with.”

* In 1939, Gandhi justified his counsel to the Indian community in South Africa against forming a non-European front: “I have no doubt about the soundness of my advice. However much one may sympathize with the Bantus, Indians cannot make common cause with them.”

There’s no doubt that a man, like Gandhi, might have first acquired prejudices of his time and culture, many of them without even noticing them as prejudices. It might also take a long time to be rid of them, often a lifetime of effort could be enough.

If Gandhi was able to rid himself of any of his prejudices against Africans (whom he referred to as Natives, Bantu or Kaffirs), it does him some credit perhaps for building a coalition in India to fight British rule.

But nothing of his achievements in India is of any comfort to Africans and the people of African descent the world over. Except, it is disturbing knowing that India’s most famous leader, Gandhi, was a racist in broad day light in his youth and a racist in sheep’s skin in his old age, after he had benefited from the toils and spoils of Africa for more than 21 years.

Gandhi would not have had a career if not for South Africa!

This comprehensive view of Gandhi’s history in South Africa has long been known on the continent if not beyond. It was only in the United States of America that white Liberals, who supported Dr. King’s Movement in order to sabotage other African American Liberation Movements, ignored it conveniently to promote Gandhi’s pacifist ideas to disarm the African American masses from actually using mass action methods to advance their struggles. Edward Roux in Time Longer than Rope, exposes Gandhi as the stretcher bearer of imperialism during the massacres in Natal.

Even in India, the facts – according to Ambedkar and Gandhi – have always been that, to upper caste Hindus, he was a champion. To lower caste Hindus, he was a hateful espouser of the caste system in all its depravity. In essence, Gandhi was a hero to upper caste Hindus, Europeans even, but by no means was he a torchlight for freedom for Africans, African Americans or for the Dalits.

Gandhi is no universal icon of any virtue.

Furthermore, Gandhi’s policies in South Africa were disastrous and a great boon for Jan Smuts. He prevented the Muslim Asians from making common cause with Africans; he changed his mind on the Pass Law deciding that carrying a Pass was good for Asians; he betrayed the Chinese and later on falsely suggested that their leader had run off with money; he split Asians by incensing Muslims; and his most daringly depraved attitudes towards Africans kept him separate from an African Educational and Social Work Commune in his neighborhood.

Gandhi was no hero. He was racist.

But the fact is: Gandhi succeeded in India and his admirers survived beyond the Pacific to the Americas where his messaging influenced even African American Civil Rights leaders. He did so because no one in India or in the United States, unlike in Africa, carefully or actually read his voluminous but mostly worthless and racist writings. Instead, they were charmed by his humble costume, his emaciated figure and the repacking of a message he knew was going to make him popular among Europeans.

Often, when we admire a quality or attribute we tend to revere the most visible espouser of that attribute. But we know that appearances are deceptive and appearances have misled many to precipitately hail people, like Abraham Lincoln, as champions only to later express remorse.

That is the situation with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and even Jomo Kenyatta. If they had known Gandhi as others in Africa did, they wouldn’t have been so hasty to express admiration or commitment to his ideology. The discrimination Gandhi practiced through professing Hinduism was what Dr. King and Jomo Kenyatta fought against.

Gandhi did not preach peaceful resistance as a strategy against oppression to all. His peaceful resistance did not extend to Africans, African Americans or the Hindu Dalits. Jomo Kenyatta and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s admiration for him was plainly erroneous.

At any stretch, Mohandas Gandhi was just another case of the pot who called the kettle black, for whatever material reason. African Americans have a name for him: a House Negro!

Amed Kinsley has done quite a job here with Gandhi – the man many in Africa and Africa America have also come to revere. But I am alarmed at the facts here. Great writing and good research are important. Amed forged a dynamic review of Gandhi here using various sources which are innumerable. All to show that the man, Gandhi, whom we have been schooled to admire, was no hero. At least to Africans and people of African descent. He was a fraud. It’s jaw-dropping, eye-watering and eye-opening. Like a friend of mine would say, ‘the more we know!’

“kaffirs” lol. goodness. how insulting.

Indeed insulting to the Z lol

Really?? This makes him fake …he was no visionary no transcendental message…means he was just an opportunist… Good of you to point this article. Thanks

a reveloution for a certain class of people it was..

“We were marched off to a prison intended for Kaffirs. There, our garments were stamped with the letter “N”, which meant that we were being classed with the Natives. We were all prepared for hardships, but not quite for this experience. We could understand not being classed with the whites, but to be placed on the same level with the Natives seemed too much to put up with.”

History can glorify and retouch the images of dead so called heroes but the truth cant be buried completly,thats why you need to always dig deeper tham the nuggets you’ve been taught growing up and find your own ideals and heroes specially as a black kid whom been fed and programmed through white supremacy education systems