NTOABOMA — Let us for the sake of our collective sanity resume our prevailing discussion about human rights and property rights: Are human rights property rights? I argue that human rights trump property rights. That human rights encompass unique features beyond the scope of property rights. In this sense, my claim is central to the argument that if abrogation of a [mere] right of property is necessary to prevent a human rights violation, then that abrogation can be justified.

For instance, in 2013, the Chairman and former CEO of Nestlé, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, the largest producer of food products in the world made a categorical statement that the answer to global water issues was privatization. His reasoning was specifically this, and has ever remained so: “Access to water is not a public right. Nor is it a human right.”

In this essay, I submit that if the reasons behind the privatization of water are beyond better management, or if the rights to water-well privileges accorded to companies like Nestlé are anything but to ensure efficiency of delivery, then, if those rights are revoked, the action can be justified in the interest of human rights; that is, in the interest of the public.

In my first essay, I illustrated the first task, the logically prior requirement, which is a prerequisite for the argument for the superiority of human rights to property rights. That is, I established that a clear enough distinction can be drawn between human rights and property rights. I showed that the complexity of the human being together with her rights cannot be reduced to the essence of a [mere] property and thus, it would be ludicrous to fashion any meaningful rights to property from human rights.

And by implication, the following statement: “Individual rights, no matter how absolute and eternal, are property rights,” which many proponents of the general theory of property rights often make is downright wrong and messily untenable.

For instance, the fellow who maliciously cries “fire” in a crowded theater violates an agreement between the theater and himself, which could be taken as a violation of property rights. This is not because he cannot exercise his right of free speech, but simply that he violates the terms of contract for access to the theater. Since a theater is not necessary for his human sustenance, he can be pragmatically restricted, or thrown out, on behalf of the theater. He has clearly and obviously violated the terms of his own contract to keep quiet in a theater. But no one has violated his human right or any others for throwing him out!

My second task is short and I shall make it briefly. In order to broaden our understanding of property rights we must acquiesce ourselves to African views on the Social Contract. That is, it is not enough to show that the human being comprises of rights beyond the scope of property. We must therefore define property vis-à-vis the human being and distinguish what features make one incompatible with the other.

The negotiability, violability of property rights.

In African nous, especially in Ntoaboma traditional law, Property is simply that [thing] which is obtained legally—and by legal, I mean by mutual contract—thereby purporting legitimate claim to ones holdings. Now we must consider what gives an individual the right to openly claim ownership. In this sense alone, right does not equal might. In other words, having a right can never derive from force. In general, a right must be given legitimately, that is by mutual contract, which means it is attached to legal codes.

Hearkening back to our example above, the owner of the theater and the audience at a performance have a mutual contract to watch a performance in silence. This means that an individual cannot force others out of a theater by maliciously shouting “fire.” One can say that by shouting “fire,” one violates the property rights of all who bought a ticket to occupy the theater for the show.

Now, this is entirely different from a violation of human rights. Of course, we have yet to define what human rights actually are and/or are not. But it will be sufficient to make a vital point now.

Human rights are non-negotiable; they are inviolable; they are inalienable and cannot be dictated and defined through a “mutual contract.” In this way, buying a ticket to a theater cannot entail the purchase of a human right. Such an activity can be termed a transaction about property rights. At most, one can say that in a civil society, say in Ntoaboma, one has a human right to engage freely, without coercion, in transactions about property rights.

However, in order to demonstrate why the right to shout in a theater is negotiable, one must consider an alternative scenario akin to the first. Let’s keep in mind that audience at a theater have signed a mutual agreement to remain quiet at a performance. In this case, if an individual shouts “he has a gun,” and there’s in fact a twenty-one year old Klu Klax Klan (KKK) terrorist clad in fully loaded pistols at a theater of prayerful African Americans—say at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC—one might be spared the violation of every others’ property rights to the quiet church, the right to their quiet pews. Property rights then are negotiable. And in this sense, when they serve the interests of all parishioners; when an abrogation of a [mere] right of property is necessary to prevent a human rights violation, shouting at the theater can be justified.

I realize that I may have further complicated the issue with tweaking the example. One might now ask: What if another individual had fired her weapon, and killed Dylann Roof, and saved the nine African American parishioners who were murdered? Can one say that the human rights of this terrorist KKK boy still remained non-negotiable or inviolable?

If I kept to the theme of the earlier illustration, that is, if an individual shouts “fire,” and there’s in fact a fire that threatens the lives of all at the theater, then one might also be spared the violation of every others’ property rights to the quiet theater. This reading is consistent, but for me, it is all too convenient since it skirts the boundary of honestly raising another important issue—the human rights of a murderer, or the difference between Dylann Roof and a thing, such as a fire, that hates life or might resolve to destroy life.

Spare me the scope of this essay. I shall not discuss the criminality involving either human or property rights at any meaningful length, since it is a matter whose latitude lies strictly outside the width of a serious scientific analysis. The debate about what constitutes the greater good in self-defense or the defense of property are peripheral to this debate. The differences between the definitions of human and property rights are a central issue while their criminology is a tangential matter.

Sticking to the kernel of a purely scientific study, Property rights then are negotiable. And in this sense, when they serve the interests of all parishioners; when an abrogation of a [mere] right of property (the contract issued upon purchasing a ticket) is necessary to prevent a human rights violation, shouting at the theater can be justified.

Human rights on the other hand are inviolable. They are so intrinsic and inalienable that they are non-negotiable. That is essentially because, one’s human right cannot be issued, purchased, tweaked, and violated without consequence.

The non-negotiability, inviolability of human rights.

The next task is to recognize the contractual nature of property so that we can distinguish it from human rights. With this perspective the rights to property and human rights do not necessarily occupy mutually exclusive spheres. There is no such contract with human rights, except for a “moral” bind between the individual and his life. The use of “moral” here is not insignificant and I shall address it in due time.

In almost all African cultures, an individual has no right to take her own life (to commit suicide is to destroy a “gift of life,” and such an act is regarded as a taboo) although she has the right to destroy her own property. Even the destruction of another man’s property is not actually a taboo but a crime. It is on this basis that one does not have the right to destroy another life. Life in African nous then cannot be legally acquired—life cannot be owned, not even by the individual who possesses it.

In Ntoaboma philosophy, which borrows much from the Guan, the Gbe and the Akan traditions, the individual does not own her life. She borrows it. She is, in one sense, a passing custodian of the life she possesses and she extends her existence within that life-span accorded her. One such exemplary tradition ritualizes day names, “Kra-din” in the Akan (“soul-name”), and which carried throughout the life of the child represents the soul which she possesses as a “gift.”

It is fair to ask the question: Who owns “life” or the “kra” that She is able to “endow” an individual with it at conception, or at birth?

Within the framework of the Social Contract in Africa, “life,” which is “given” (as in a gift—endowed, or a natural ability) invokes a supreme being in much the same way that a physicist might invoke a “supreme being” without the explicit insinuation.

For example, the source of the motive forces of electrons around the nucleus of an atom is taken as a “given.” That is, it cannot be explained. The source of the pull of gravitation is also taken as a “given.” One can say both are regarded as “gifts.” Notwithstanding, we can only induce that these pervasive phenomena exist everywhere else, at all times, and that we can attempt a description of them. Much the same way that the source of “life” in African nous can be described. Whether the Big Bang or the Primordial Nun is the adequate explanation for the source of life or the motive force of electrons is not the subject of this essay. Suffice it to say that both are candid attempts.

Taken together, the sources of gravitation and electron motion are only defined by natural laws. Another way to put this is that natural laws are “given.” So at best what philosophy can do is to adequately acknowledge this given “life” as a human right assigned to individuals by a motive “source,” without conflating its sublime nature with some sort of an “ownership of life” by the individual who possesses it. Another way our ancient philosophers in Ntoaboma put it: “One cannot own what one cannot will.” On the contrary, the right to property, as in property rights, can be willed into existence with a mutual contract between individuals.

To appreciate this technicality even further, it is not difficult to see how the idea of a given life may have reached Ntoaboma via Kemet (KMT). On a monumental inscription of Akhenaten the illustration that life is “given” becomes all too familiar:

Oath spoken by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt who lives by Ma’at, the Lord of the Two Lands, Neferkheprure, Sole one of Re; the Son of Re who lives by Ma’at, the Lord of crowns, Akhenaten, great in his lifetime, GIVEN life forever.

Life then is a natural law and it cannot be owned since there’s no such thing as a legal contract for obtaining it. This much is clear and supremely edifying since if there was any such legal contract, the Rothschilds and the Rockefellers, some of the biggest butchers and terrorists the world has ever known, would attempt living forever without actual heart transplants from actual human beings.

The rights accrued to life then are human rights. The rights accrued to the elements of the environment to sustain life then are human rights. The rights accrued to a river, since the river lives and dies, are river rights. The rights accrued to a forest, since the forest lives and dies, are forest rights. In Ntoaboma law, anything that lives has intrinsic, inalienable, inviolable rights which supersede the rights to ownership, or the rights to property.

But, let us for the sake of simplicity narrow our discussion to human rights alone.

The amalgamation of individual rights.

In Ntoaboma parlance, once a right is established, it is beneficial and necessary for the individual to apply this right effectively for his best interests and those of the whole. This motivation is directed at the formation of community thereby creating a social contract between individuals that come together to act as a group. However, it is worth noting that within this framework, the definition of the “individual” is not in any way limited to human beings. Individuals comprise of all life-forms—the river, the lake, the forest, the animals and the land.

Now, a combination of rights is formed whereby each individual is protected by the whole group that stands together as a community. The concept is that a woman standing alone—without other women, without a river, without the land, etc.—is more vulnerable than many women united each in defense of the other, in defense of the river, in defense of the land, in defense of the forest. This condition makes it impossible for an individual to hurt another individual, to poison the river, to indiscriminately kill animals, to burn the forest, to toxify the land, without hurting the whole group or for one to hurt the group without affecting each individual.

One can harness a refreshing implication of the amalgamation of individual rights when we reconsider one of the examples we have discussed above. The right then for one parishioner at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC, in the U.S., to pull out his gun and defend himself (and perhaps the other eight parishioners), from the terrorist, can be justified since the condition of a community makes it impossible for an individual to stand idly by while a terrorist destroys his community.

In this sense a terrorist who attempts, or succeeds, in hurting members of a community has already destroyed himself within that community. Since he has destroyed his community and himself (which was a taboo), the abrogation of his [mere] rights would have been justified to prevent a human rights violation a priori. That abrogation can be necessary in self-defense if in fact one can prove that the sanctity or the indefeasibility of the amalgamation of individual rights, the collective individual rights of community, was at stake.

This reading makes clear that an act of self-defense, for instance, does not infringe upon the definition that human rights are inviolable, inalienable, non-negotiable and indefeasible.

Furthermore, within this structure, it will be intolerable to grant large multinational beverage companies water-well privileges (and even tax breaks) over citizens than water rights to all taxpaying citizens. If companies such as Coca Cola and Nestlé (which bottles suburban Michigan well-water in the United States and calls it Poland Spring) suck up millions of gallons of water, leaving the public to suffer shortages then the abrogation of their contract in the interest of the public good can be justified.

The social contract where individual rights are combined then can prevent devastating repercussions of multinational corporations while at the same time laying down the foundations for the rule of law and punishment. It is in the best interest of the individual to give over his rights to the group since he has a more powerful protective base than standing alone against Coca Cola or the terrorist Dylann Roof.

Interdependence becomes the key resultant philosophy. This is why in Ntoaboma, one cannot own land. One is only a custodian of land. Land, which has its own life, cannot be owned. In this sense land is held in trust for the next generation. The land belongs to the community, and by implication cannot be “sold to” or be “purchased by” Coca Cola or Nestlé.

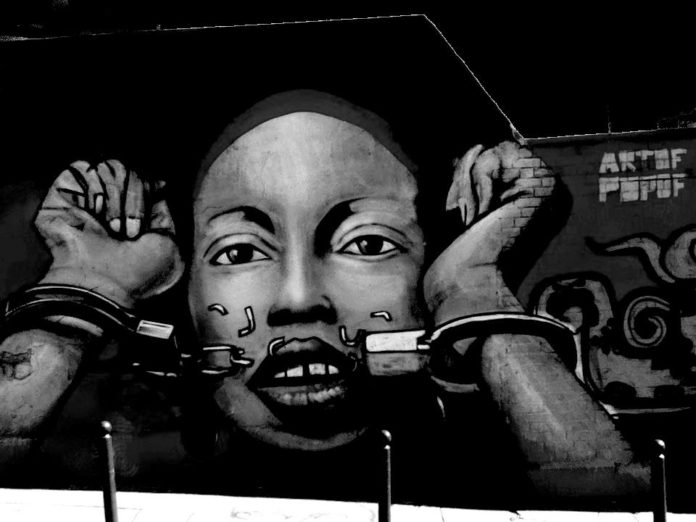

Among this foundation, one cannot go without noticing the relentless attack on such African ideals. The insanity of the anthropocentrism of western philosophy that is rooted in the “holy” crusade of capitalistic endeavor continues to plague African scientific and philosophical inquiry even today. And perhaps, either through colonialism or sheer stupidity, our nations continue to lose much of their ancient philosophy to proponents of property rights.

By invoking the idea of ownership, an individual can own herself and everything in her community, up to and including the river, the lake, the land and the mountain. It removes her sense of exercising restraint with herself, with her community and with her environment. In fact, one can argue that ideas of property rights disbands the essence of the ideas behind a sustainable economy and community.

In this respect alone the idea of property rights as a general all-encompassing feature of humanity and her environment stand in contradistinction from the African nous.

What are the motivations behind equating property rights with human rights?

But all things, even ideas, are not without motivation. What inspires the African nous about human rights, river rights, land rights and animal rights are not the same incentives at the base of the anthropocentric European philosophy. Such provocations to the equilibrium that African philosophy offers is not without intent. There is a reason.

European economic thought seems to have influenced much of their philosophy. That the theories about commerce in Europe are based on the “lack of resources” for the human, or a penchant for “over-eating” by the human, are not difficult to unravel and understand especially since they were propounded during a period in which Europe overbred beyond the threshold of a stable population. The lack of constraint, the lack of restraint and discipline in European policy initiatives produced an imbalance between overpopulation and limited resources. This formed the stage for aggressive theories about property and ownership to imbue law and order in an otherwise chaotic environment.

However, instead of addressing the internal issues, and perhaps returning their nations to equilibrium, European governments sought rather to expand beyond their borders in a crusade to loot more and more resources from elsewhere, from distant lands, which they saw and continue to see as a “limitless abyss” to be used for the gratification of insatiable human appetites and “primitive accumulation.” The profits amassed from these escapades provided the instant fleeting relief from internal indiscipline.

For the European elite, the human right of every man to his own life then implied the right to find and transform resources in Africa and elsewhere other than in his own environment: and to produce that which sustains him alone, and advances his life alone. That product by a man’s efforts, is what the European philosopher called the man’s property. For an ideology to justify the looting of other people’s lands, after the same philosophies had decimated their own lands, the European elite set out to push their designs that property rights were foremost among human rights. That any loss of one endangers the others. In short the intention is simple: the European has a human right to come to Africa and burgle as much as he can. That he has the right to extract and pillage as much as he wants from the Earth, whether it puts the planet in peril or not.

It is with this solid appreciation for European historical thought that one can grasp the unique turn of events in Europe that gave rise to an aggressive worldview and which single-handedly fueled an industrial revolution, and now having expanded everywhere else, this monster, this “hatred of life,” threatens the life of the planet itself. With over fifty percent of the world’s species now extinct—we lose about one hundred species daily—western nations continue to double-down on the same unsustainable worldviews, the same insatiable economics and an unchanging indefensible philosophy.

Take for instance the small Pakistani community of Bhati Dilwan. A former village councilor reported that children are being sickened by filthy water. Who was to blame? Bottled water-maker Nestlé, which dug a deep well that has deprived locals of potable water. “The water is not only very dirty, but the water level sank from 100 to 400 feet,” Dilwan said.

Why? Because if the community had fresh water piped in, it would deprive Nestlé of its lucrative market in water bottled under the “Pure Life” brand.

Lagos is one such other example. In Nigeria, Gehriger discovered that families spend up to half their household budget on water in canisters, and that only those who can afford it drink “Pure Life.” Then there are the communities in the U.S. state of Maine who are fighting Nestlé because it pumps ground water and spring water in huge quantities – which it can do legally: whoever owns land can pump as much water as they like.

It is with this motivation that the propertied classes of the west continue to push the neoliberal ideology of property rights.

The need for restraint, for internal balance.

But the need for internal balance is necessary if the planet must be saved, and if life on this planet must once again become revived and sustainable. The continued lack of appreciation for the African nous only puts the world in peril. The indiscipline of western ideals and its rising appreciation among the rising elite in Africa, and everywhere else, only puts the planet in further jeopardy.

It is also vital to concede that the conflict between property rights and human rights will continue as the west gears up and continues to pitch its economics paradigm to all its puppet governments, even as they continue to inflict the pain of western philosophies on the humble peoples of the world. Under the oppressive powers of the west – under NATO and AFRICOM—it is difficult to see through the pale curtains of time and space. But in this century, few African scholars would accept to keep silent. For this reason the debate has entered a new chapter.

I realize that it is a debate that cannot be won, will not be won, in a decade or two. However, I believe that the dialogue must be removed from its prior setting, from the events that led to the rise of the feudal lords in Europe—those proponents of “primitive accumulation—” and from the vast expanse of colonial realities around which the world supplied these lords with the fuel to grow and amass unseemly wealth, and be carefully situated within the safe space of African experiences, lessons, wisdom and nous.

That today, the ninety-nine percent of poor Africans and destitute Americans challenge the super wealthy or the one percent (actually the .001 percent) is by no accident. In the United States alone, there is a new battleground in what’s known as the housing market with as many as fourteen million people in or facing foreclosure. In Africa, the effects of imperialist policies have exacted so much havoc since colonial occupation. But in this century the dangerous effects of the carefully framed neoliberal ideology, which was supposed to uplift millions out of poverty in the freshly independent balkanized states, are newly coming to light.

The people can no longer be deceived. The truth about the defense of property rights as the holy of the holies for the propertied classes of the west with a whole industry set up to enforce their claims of ownership, must, in the final analysis, be revealed.

I think, and this is my belief, that the new breed of African philosophers and thinkers are paying close attention and repudiating the western capitalist claims that property rights – at least some, and perhaps even all – are human rights. To allow such a premise to take hold in Africa and subvert the African nous, will be to hand western nations the justification they need to continue to despoil our continent without regard for the sanctity of life.

Careful framing of neoliberal elitist policies are necessary to combating unfettered capitalism.

In order to completely debunk the western elitist form of thinking everywhere and particularly in all African nations, we need to distinguish three main types of claim that might be made in general argument in order that we might move the discussion beyond pettiness. I shall quickly clarify the three points. The first two help us understand the last claim and provide a practicable basis for refuting it.

The first is that, in African nous, sometimes the substantive ends of human rights may require provision of additional positive property rights as an instrumental means to safeguarding them – as, for instance, when a member of the community and her family could have their livelihoods protected by means of recognizing secure rights of theirs in relation to a decent tract of land for farming, shelter and the rearing of animals. This kind of claim allows instrumental justification for specific rights of property in particular circumstances.

The second is a derivation of the first. That a right to be recognized as a person, a member of the African community and say having the right to become a custodian of land, can be defended on a human rights basis, at least in the circumstance that property ownership is allocated to all people in a community. For it could then be regarded as a necessary condition of equal membership of that society, which is a human rights value. This is a procedural right.

Both such justifications, appropriately applied, can succeed alongside the overriding implication of inviolable, inalienable, non-negotiable human rights.

But a third, which I have argued throughout, cannot: this involves the claim of the propertied classes of the west that there is a general and substantive human right of property. In other words, human rights are property rights. Exactly what such a claim means baffles interpretation in light of the distinction clearly enumerated here. However, one cannot discount the tenacity of the propertied classes in the twenty-first century. They cannot let the backwardness of “primitive accumulation” give way to the more enlightened ideas of African nous.

Why? “Primitive accumulation” itself is a disease without boundaries, without restraint, without self-control, and without self-discipline. It is a disease so putrid and so contagious in its manifestation that Mother Earth is at the brink of utter destruction because of it. This disease does not understand moderation, it does not comprehend prudence, it does not appreciate judiciousness, and it is certainly oblivious to abstemiousness. This disease lacks tastefulness and scorns discretion. All it grasps is how to plunder; all it knows is how to exploit our Great Mother, Asase Yaa.

Our job, as African philosophers, and thinkers, is to refute the third claim, at all costs. It had no place in all ancient African nations, it has no place now, and it should never have a place in our collective future.

If the only “right” of naturalistic man in a secular world is the “right” of the fittest to struggle to survive longer than others—to engage in the most abhorrent “primitive accumulation—,” then we shall live in a world of a merely accidental opportunity for uninhibited selfishness. No one then would have the “right” to challenge the landlord or the feudal lord or the plantation owner. No one can suggest the exercise of restraint, of abstemiousness. For in the final analysis the community ceases to exist, and each man will be for himself, God for us all.

That is the definition of a jungle, the definition of insanity, of a lawless unbalanced commune of humanless, inhuman, inhumane “matter” in constant struggle to explode from its infinitesimally minded consciousness and reach beyond the excesses of a Big Bang. Such a world will take another 14 billion years to emerge from its chaotic order, another 5 billion years to tame a niche within it and some millions of years to impose Ma’at on its sheer barbarism. Narmer Amenuti takes as through the difficult steps, purposefully studiously, to comprehend the motivations inherent in the neoliberal doctrines of “Scarcity” and “Property Rights” underlying the attempts by western philosophers to impose dangerous ideologies of the hatred of life on us. He beseeches thinkers on our continent to rise up and see the light. Be bold and courageous.

Enjoy! By all means!

What an undescribable joy to wake up this morning to another conscientising outpouring of the intellectually honest Pan-Afrikan revolutionary brilliance of our Brother Warrior-Griot Gbetodzokanitsola Asafoatse Osabarima Narmer Amenuti! Yes, we must heed the exhortation of Sister Akosua Abeka to be studiously diligent, bold and courageous in rising up to see the enlightening Freedomtorch of our global Pan-Afrikan Liberation Struggle that Narmer Amenuti and others at Grandmother Africa are trying so laudably to rekindle with such expressions of the Walter Rodney-type of “Pan-Afrikan Revolutionary Guerrilla Intellectual” Afrikan audacity as in this expose on property rights in relation to human, peoples’ and Mother Earth rights from our own ancient but still valid “Sankofanunyansa” perspective of Ma’at! This is not another appeal to the non-existent consciences of the elitist bands of stupefied “condidates” and their ilk of criminal gangsters, inextricably tied to the leash of the White Supremacist Coloniality of Global Apartheid Racism, who are jockeying or already positioned to continue misleading gullible Afrikans into the Maangamizi Genocide/Ecocide slaughterhouses of Neocolonialism, in the dirty mercenary-puppet neoliberal capitalist service of Euro-Amerikkkan Imperialism! This is a signal to those from the new as well as old generations of courageous seekers of our own Afrikan Wisdom who are desirous of being the Pan-Afrikan Revolutionary Change they want to see for the definitive self-emancipation of our Afrikan people all over the World! Ayekooo, Narmer and all at Grandmother Africa! Elavanyo! Tswa Omanye Aba!

Mawuli, your phraseology is set in the sky! Do you perchance have a running dictionary of these? My favorite so far is “Sankofanunyansa.” I gather we can fashion new phrases and new vocabulary with all our languages put to together. I don’t mind popularizing them in my writings! Thanks for gracing our articles with an intriguing breath of Afrikan sentience. Mawuli! Elavanyo! Tswa Omanye Aba!

Excellent article by Narmer Amenuti. I agree 100% with his premises and conclusions. I believe I stated in response to his earlier article on the same topic that human life is not even owned by the possessor of the life. He is correct.

You are correct. It is truly impressive your understanding of African traditions and philosophy. Absolutely you mentioned that in our last conversation.

Deep word, 100% thumps up

This is a signal to those from the new as well as old generations of courageous seekers of our own Afrikan Wisdom who are desirous of being the Pan-Afrikan Revolutionary Change they want to see for the definitive self-emancipation of our Afrikan people all over the World! Ayekooo, Narmer and all at Grandmother Africa! Elavanyo! Tswa Omanye Aba!

Narmer Amenuti, your strategy is to “Shock and Awe.” You don’t let up. You overwhelm your critics. You beat them down with ever newer ideas, with ever expressive diction, conciseness and sheer discipline about the explanations of the truly African sense of the world. From the last essay about property rights, this is the third I have counted. And in all you seek to entrench emphatically the essence of the African understanding of the world. Together with the likes of Atiga Jonas Atingdui you guys rock a precise spirit of purpose in confronting like with like, sheer intellectualism with intellectualism wherever you engage it. This is a discipline I am seeing from grandmother, and nowhere else, that gives me hope. The discipline to overwhelm with focus, with understanding and with the character of truly Afrikan intellectuals. Children will learn from this bravery one day. They will.

As for me it seems that the debate will continue, even way into the future. I am glad you appreciate the need for this. But it will continue with the arsenals you continue to provide. This is what African ideas can do, and you are defining what these African ideas are. The tools for confronting the outside world are taking shape here and I am glad I am here to see it. No more beating about the bush. No more waiting to be published in some “ritzy” journal heavily guarded by Afropeans or Europeans. No more. We define our own spaces.

I have gained a deeper meaning on human rights now. A deeper meaning about property rights too! And every day I read the arguments I am more refreshed into solidifying my conviction of the superiority of our Afrikan philosophies on shedding light on this torrid topic.

Dade Afre Akufu, everybody at Grandmother knows you are the ultimate “Shock and Awe!” You come gun blazing and you dig, deep! There’s no writing without able supporters and critical minds like yourself. Thank you!

HAHAHAHAHAHA…. I doubt it. But it’s all in good humor.

Great read. I am convinced that we do not own ourselves or any property but that the community is the protector of all. Therefore we must build strong communities to stay protected. I will keep this article to read again when I need a refresher on why private ownership is a horrible idea.

Indeed Dade Afre Akufu, Narmer Amenuti showed great intellectual insight into African philosophy and world view. Such exegesis is always more refreshing than the stale ideas of most western philosophers.

Very well put, my Brethren Narmer Amenuti, Dade Afre Akufu and Atiga Jonas Atingdui, like all our Sisters and Brothers of Grandmother Africa! You all rock with the kind of our Pan-Afrikan People’s Power no one dares, at their peril, to mess about with! And so must it always be from now and forever!