The term “modern,” we think, sounds more advanced than say, “traditional”—to the extent that we’ve come to revere the modern and revile the traditional.

In the world of home finishings, for example, modern accoutrements like granite countertops, stainless steel appliances, and hand-scraped hardwood floors are the crème de la crème, while lackluster laminate countertops, bland white appliances, and nauseating carpet are, well, substandard.

Sure we can agree that these aspects of the modern/traditional divide are mere aesthetics, matters of taste and preference, and not of real import to our daily lives, much less our society.

Yet, this treatment of modern and traditional, heralding the former and disdaining the latter, influences our purview of the social world, and not always rightly so.

For some, the difference is a matter of decades that span between our generation and our parents’ generation, between the physical laborers who toiled on the farms, day in and day out, and the mental laborers who are dealt their most taxing ordeals from the hands of middle managers and temperamental computer systems.

But work by any other name, or form, is still work, is it not?

Actually, the old, conventional version of work is quite a bit more attuned to ownership.

While planting tomatoes, maize, and plantains on the farms, many of our parents built their homes from the ground up, homes that do not require monthly or yearly payments for renewal.

Rather than replicate this model for living, we choose to aspire to dreams of modern affluence.

True upward mobility is not to equal one’s parents but to do better—moving out of the village, earning an advanced degree (or degrees for the overly ambitious), and not having to walk miles to fetch water.

Obviously the city is more cosmopolitan than the country. One can barely know how to get out of bed with a basic education, much less make something of his life. As for indoor plumbing, that goes without mention.

Besides the superfluous comforts that these modern achievements provide, what else do they accomplish? What do we possess as a result of their intrusion into our culture?

Ironically, what we possess pales in comparison to what we owe.

Many of us do not own our education, at least not yet. For the present, we are buried in thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of dollars in debt.

We find ourselves in a similar situation in the housing department, especially for those living in the world’s biggest, most flamboyant cities. The dream of affluence is marketed through these hot spots for the vibrant, young, and hip trendsetters, with bars that never close and constant flows of social traffic—sightseers, vacationers, visitors, new and old residents.

Amidst all that transient hype is the reality of renting.

To own in New York City, for example, one needs a down payment plus a loan of at least in the amount of half a million dollars, and that’s exclusive of homeowner’s association or co-op fees and property taxes. Such a glamorous lifestyle in a big city forges an impossible distance to ownership.

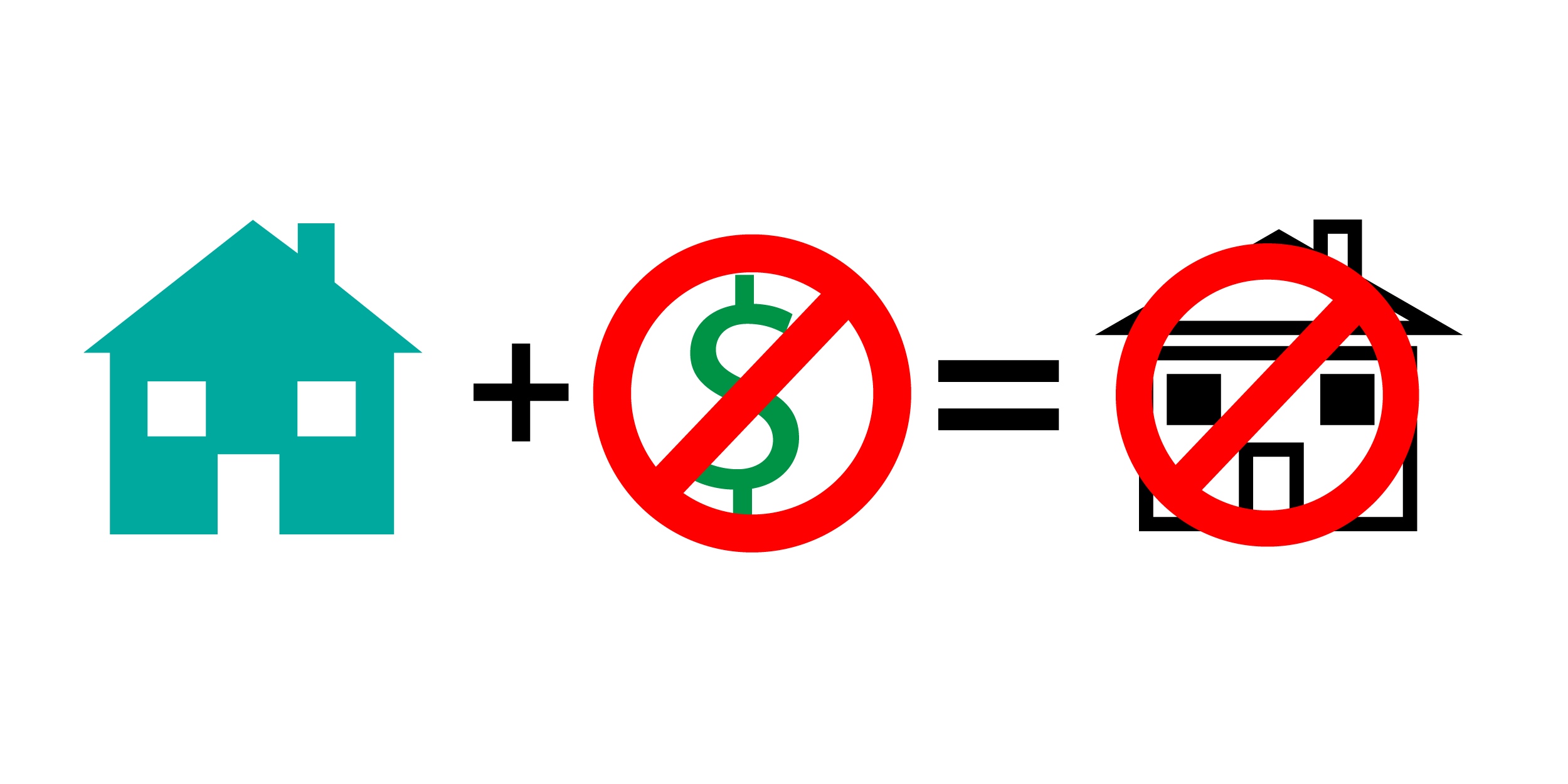

Even when ownership of one’s home is tangible, it is often not probable, at least in the sense that the home will be paid in full in the foreseeable future.

In Britain, houses are being poorly constructed, so much so that a full price house would hardly last thirty years without major renovations being necessary. Moreover, homeowners are being forced to lease land rather than buy property, posing a problem for homeowners and only benefiting litigators.

This lack of ownership is a symptom of the modern world. We are clearly not free if we are tied to monthly rent, automobile, and student loan payments.

It is a great fear of our time, and one not to be taken lightly, that the day will soon come that we will not own anything outright and in its entirety–the day that we will be forever contractually bound to borrowing.

Or is this day already upon us?

How far we have come in this modern, technological, advanced, developed world, that we have no homes to pass down to our children, no automobiles that are safe from repossession.

Are we so blinded by shiny, new things that we are fooled into thinking it is better to lease hardwood floors than to own carpet?

Would your grandmother accept that she could eat the eggs but never own the chicken? Or drink the milk but never own the cow?

Perhaps it is due time to reevaluate the connotations we associate with the modern and the traditional, if only so that we can own something in our lifetime.