“The more connected you become with Asase Yaa — even lying bare-naked on Her — the more grounded your ego, pretensions, and appetites, and the richer the soil of your soul becomes. Grounding enables you to discover through newer eyes, and not through bigger, sharper swords.” ~ Mama Huegbadja Mlagada.

NTOABOMA—When I was a child, I usually walked on the balls of my feet. Some said the posture made me run faster—but not longer—than any boy my age. My heels barely touched the ground. I made the sprinter’s mark in elementary school, and middle school and then secondary school as well. I always made the school team, usually as the fastest. Although after the hundred and two-hundred meter individual dashes in an Inter-School competition, I barely found enough energy to help my teammates, the best I knew how, to get a decent position in the relays.

I walked barefooted, all the time. Of course, this was Ntoaboma, a village neatly tucked away along the Eastern foothills of the Afram Plains. Everyone walked barefooted, even the Chief, and of course, the Priest. Our feet left full footprints in the sand even as we walked out of our bedrooms. But walking on the balls of the feet was new, at least to those who made me aware of it. Or, it was perceived as a bit weird. My great grandmother would always bawl after me whenever I left her room on a new errand: “Put your heels on the ground, my son!” I would smile and run-off, knowing full-well that her head swung from side-to-side in disbelief.

In my great grandmother’s compound, and around much of the village, everyone knew when and where I had been because of the balls of my feet. That is, I could be tracked. My footprint had no heels. Which got me into lots of trouble since I couldn’t deny the size and contours of my footprints. Years later, when I could actually recall and recount what a great grandmother told a great grandson, she beckoned me over to her bedroom, and as she sat on her mat, on the ground, the mosquito net hanging over her head, she advised: “Son, why can’t you keep your heels on the ground when you walk? Do you know what happens to people who walk on their toes, never allowing their heels to touch the ground?” Obviously not, shaking my head and knowing that she had asked a rhetorical question, which needed my urging in order for her to speak on. I did and she continued: “You walk on your toes long enough, the connection between your heels and your brain will break. You will lose your mind. You might even become a thief, tip-toeing everywhere you can find anything to steal.” I smiled at my great grandmother. She returned the smile, hugged me and waved me away.

By the time I started secondary school, I no longer walked on the balls of my feet. In fact, I left some of the finest footprints in the sand in Ntoaboma as a result. I am not boasting. My middle-school girlfriend—the only girl I would share Agbelikaklo with—could still track my whereabouts notwithstanding my longer footprints. Which was comforting—I didn’t want to lose that connection, if the connection between my heels and my brain was something that, according to my great grandmother, I had to maintain. The days of half footprints were behind me as I moved into boarding school a couple hundred kilometers away. Three months later, I returned to Ntoaboma, in the full regalia of a boarding school boy: a pair of rubber-sole Achimota sandals, a school uniform, a leather bag (full of English books) and a new shave.

The whole village was elated when I alighted from the only lorry that plies Forifori and Ntoaboma, the last part of the trip home. Even the barefooted Priest, on his way to a holiday ritual, waved to me: “God Bless you my son,” he said. When I entered my great grandmother’s compound, everyone present erupted. It was as if the letter I had sent home about arriving that day never made it home, or was never read by one soul, which probably was the reason. I had sent the letter (my first letter to Ntoaboma) in English. What did I expect? My grandmother or my great grandmother to read a letter in English? I received a rapturous reception home with a thunderous heart and a beaming smile. My youngest aunty fetched me some water to quench the thirst, and then she poured the libation for my safe return home as I sat in the middle of the compound, everyone gathered around.

“Take those things off your feet my son!” Stormed my great grandmother as she entered the compound from her living room, barefoot, her eyes fixed on my neatly polished rubber-sole leather Achimota sandals. “Oh, great grandmother, this is how they do it in boarding school. This is how Ayevuwo [white people] dress oh,” replied my aunt. “I said take those things off your feet.” And turning to my aunty, “Ayevuwo dress? You mean shoes? You don’t think we’ve seen these things before?” My aunty went mute, turning away so as not to engage the wrath of my great grandmother. “Son, they will make you sick, take them off.” I obliged as my great grandmother approached and hugged me so tightly: “Never wear those things again. They’ll make you sick.” When she finally sat on a stool next to me to welcome me back home, she explained further.

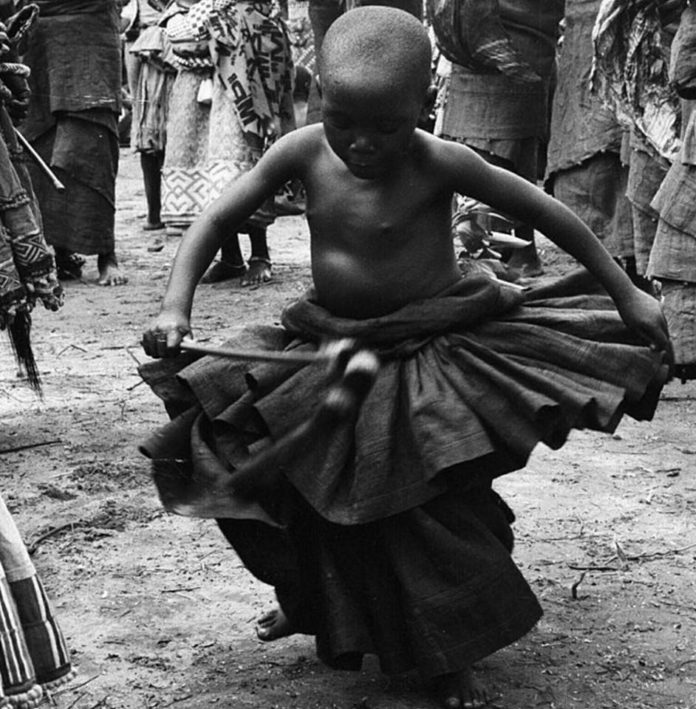

“Do you remember I always told you to keep your feet on the ground? To keep your whole feet, your toes and your heels on the ground? You know why?” I nodded to urge her to go on. “It’s important to maintain your connection with Asase Yaa (Mother Earth). Your body needs it, your brain especially, and it is through your feet that Asase Yaa can absorb all the noise [off-rhythm] in your body, and nourish you and re-nourish you with her rhythm. And remember that rhythm is everything. It’s the only way to maintain our sanity in this world. It is vital for balance. It will help you see with newer eyes. The more connected you are with Asase Yaa—even lying bare-naked on her—the more grounded your ego, pretensions, and appetites, and the richer the soil of your soul becomes. Those who wear those things [shoes, sandals, socks, etc.] everywhere, even into their bathrooms, and who sleep on beds insulated from Asase Yaa eventually become sick and fall out of balance with Asase Yaa. They begin to discover everything around them by the sword, not through newer eyes. Don’t forget that you are here because of what’s in there [pointing to the sandy ground beneath our feat]. Don’t forget it, my dear son.”

Years later I would make sense of what my great grandmother said. I would make sense of why our ancestors in Kemet, despite their unparalleled achievements in civilization, from building Pyramids to discoveries in medicine, still chose to go about their duties barefoot, most of the time. I would come to understand why our ancestors only wore sandals or shoes for special occasions or if their feet were likely to get hurt on an occasion; in the same way as we still do in Ntoaboma today. I will come to appreciate that in Kemet although they made sandals with papyrus, palm and leather there was never a mass consumption of shoes and sandals, which is sadly now the case in boarding schools today.

The connection to the ground, to Asase Yaa, was then paramount in maintaining Ma’at in Kemet, as it is still vital for maintaining balance, in any given individual, and in any given population in Ntoaboma. Which leads one to make sense of the havoc wreaked on Ntoaboma and beyond, in recent memory, by the rubber, leather and glue-sole wearing colonialists and slave raiders who arrived in West Africa since 1492. It is also no wonder then that Europe’s first encounter with Africa in modern times would result in the looting and the terrorism of Africa. Perhaps the nature of the cold icy conditions of the North, requiring shoeing, or sandaling, at all times, led to the rise of a population of The Insane, The Sick, The Disconnected, from Asase Yaa, capable of all the devastation visited upon the Souls of Africa and in fact, the rest of the world. That population, of The Unrhythmic (The Noisy), The Insane, The Sick, and The Disconnected still poses the greatest threat to Africa, the survival of all species and the entire planet.

For in the last two centuries alone, Western Barbarism, epitomized in its un-Holy Trinity of primitive accumulation, over-consumption and loony ideas in economic growth, has led single-handedly to the destruction of over seventy-five percent of all Earthly species and counting. Western lack of rhythm, imbalance and savagery has achieved such technological barbarity as the number of thousands of A-bombs capable of blowing up the entire planet in plumes of smoke a hundred times over. Who would have thought that perhaps the lack of grounding would be at the bitter roots of this unparalleled violence? Who thinks that such people with such tools of barbarism aren’t imbalanced, aren’t so disconnected from Asase Yaa as to be able to permanently destroy Her and then cause their auto-extinction? Who thinks that these grim reapers aren’t actually sick?

Now, a mighty take on what it is that plagues a dying planet, if a dying planet that is. Narmer gives us another enigmatic fable from Ntoaboma, emphatic in all its trappings, the story of a noble cottage and its difficult encounters with a fickle, fast-moving world; its stumbling upon a new world disconnected from much of Asase Yaa (Mother Earth).

If there’s any hope left for the planet, and thus any hope left for the rubber-soled sandaling West, it would not be because of its psychotic belief in its own exceptionalism or its risible grandiosity involving the claim to be the one and only “indispensable world.”

Conversely, its best quality is evinced in the voices of Africans in the diaspora, the country’s economically bereft rabble, as expressed in the blues, in jazz, rap, country/western, and hip hop music, in which the powerless, in which the children of Asase Yaa, find a voice that moves the heart by inducing the soul to be able to penetrate the thick walls of shame that the race-based capitalist prison states of the West imposes on the world, and on Africans in general.

I like this your piece. Though I’ve been galloping more towards irreligiosity the greater my wedding to rationalist approach to issues, mother earth and our sun will forever remain the nearest to our ultimate parents, worthy of our acknowledgement. We in West Africa in particular need to blame ourselves also, and not only European contacts, for the fact that now we have fauna names in our local languages with fewer and fewer animals remaining in nature. We probably need to do more raising game animals as farm businesses, have more fish farms, and maybe reintroduce many of the animals whose names we have in West African languages but now exist only in the southern parts of the continent. We’d need to create national parks and nature reserves.

Point taken. Although it is a tad bit impractical to blame the folks in the neighborhood for the mass shooting. There’s a point to be made that folks should hence be cautious as they navigate their own neighborhood. But the blame lies in the laps of the mass shooter.

“The idiot stare of the encompassing dome of the Empire West’s skies is too much for my Ntoaboma Afadjato mountains country psyche. There is no green-on-green canopy to filter the relentless sheen of sunlight. It renders me manic, angst-ridden, and sleepless.

The damp evening air envelops one at sundown in New York City, London, Paris, Toronto and LA. It gets damn cold. A clinging chill wafts from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But the phenomenon is not weather related; instead, the cold is the embrace of the ghosts of the dead dreams of the city’s long buried enslaved African builders.”