DALLAS, TEXAS — In the United States, a second person has been diagnosed with Ebola. The newly Ebola-positive person is a female health worker who gave aid to Liberia native Thomas Eric Duncan, the first Ebola patient in the U.S. who was pronounced dead earlier this week.

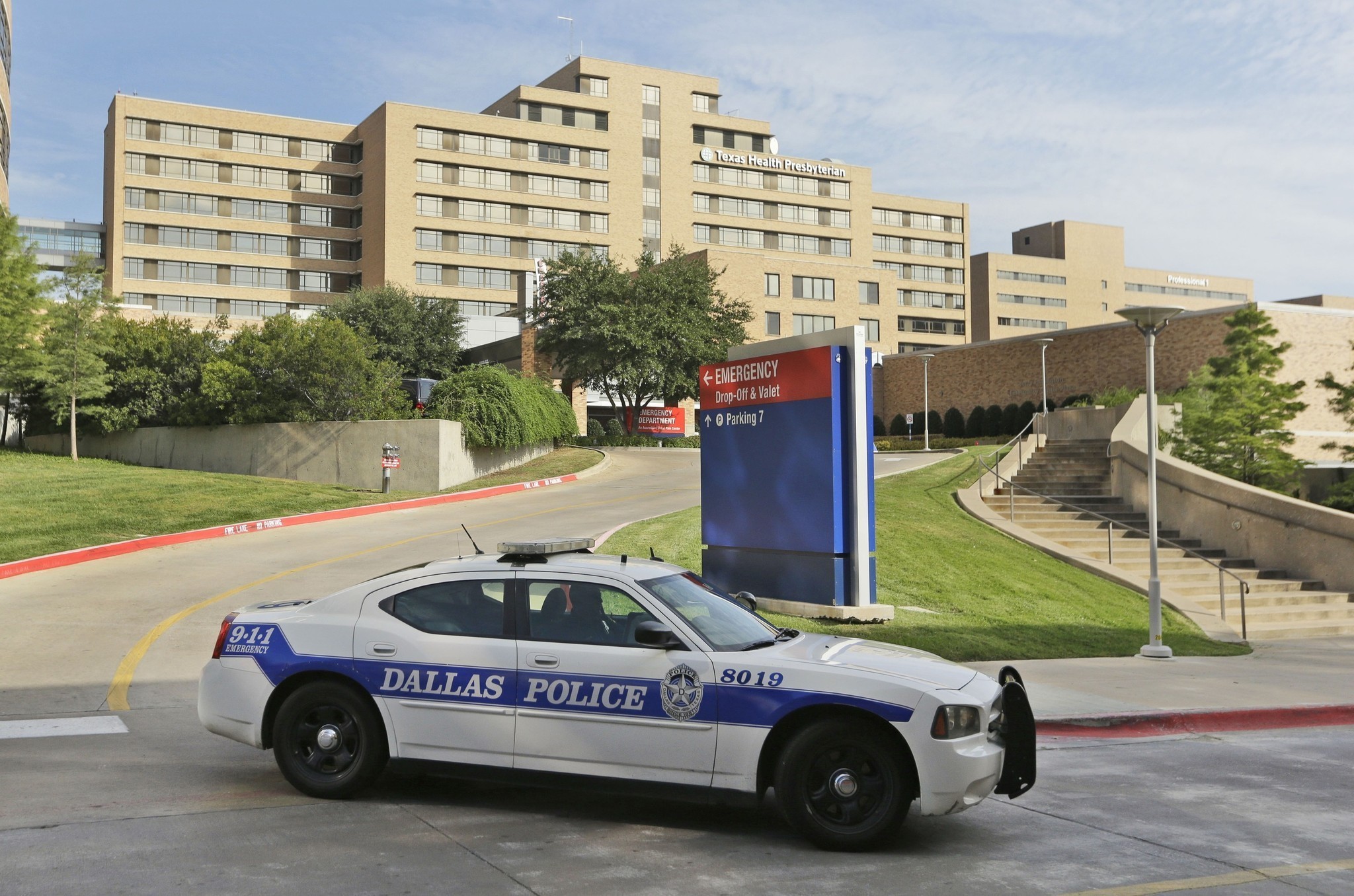

The female health worker is currently in stable condition. On Friday, she reported to Texas Health Presbyterian, the Dallas hospital that took in Mr. Duncan, that she had a fever. She was admitted and placed in isolation less than 90 minutes later.

Her contraction of the disease puzzles many since she was wearing full protective gloves, gown, mask, and face shield when she was in contact with Mr. Duncan. Initially, she was not one of the dozens of workers who were thought to be most at risk of contracting the disease.

Officials from the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia made a statement that a breach in protocol, possibly when removing the protective gear, led to the female health worker’s contraction of the disease. Another potentiality, though one not outwardly entertained in U.S. media, is that the protocol may not be entirely adequate.

Proper use of protective gear often requires a minimum of several months of training for maximum effect.

For many African healthcare workers, a 30-minute decontamination bath—which involves spraying the suit with a chlorine solution—is required prior to removing the contaminated gear. No such process is routine procedure in the U.S. In this case, cautionary standards for preventing the transmission of the virus in the Dallas hospital may be far lower than standards practiced in Africa.

News reports about the second carrier of Ebola assure residents in the United States that local hospitals and the CDC have the situation under control.

One measure involves increased screening of airline passengers.

Major airports like Dulles in Washington D.C., John F. Kennedy in New York, Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta, and Newark Airport in New Jersey will enhance screening for possible signs of Ebola, including measuring the temperature of travelers coming to the U.S. on flights originating in West African countries to detect for early signs of the virus, including fevers.

Yet some observers believe the calm from the government and health care departments only serves to prevent a sense of panic from rising among the populace.

Some Americans are calling for bans of flights with passengers from Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

Though such a ban would also affect United States citizens who reside in or engage in frequent travel to these countries. The interconnectedness of the world’s states renders the likelihood of closing off travel to any region improbable.

In its first ever episode of Ebola, U.S. hospitals failed to successfully treat Thomas Eric Duncan.

Mr. Duncan’s family is preparing to sue the Texas hospital, which initially sent him home with antibiotics before subsequently admitting him to the hospital, testing him for Ebola, and administering treatment.

Mr. Duncan’s family, along with Civil Rights activists, claims the hospital’s response to his case was disappointing and unsatisfactory, though hospital workers deny that they discriminated against Mr. Duncan due to either his West African nationality or his lack of health insurance.

Although some purport that Mr. Duncan gave false information to airport officials about his contact with people who had Ebola in order to enter the United States, such claims are mere speculation at best.

As Mr. Duncan is deceased, no one can ascertain whether he knowingly had contact with Ebola-positive individuals or whether he was unaware that any people he had been in contact with carried the disease.

Besides Mr. Duncan, other infected patients in the U.S. seem to be recovering from the disease.

Widespread Ebola panic in the United States should lessen in the coming weeks if patients’ recovery continues and no further incidents emerge.