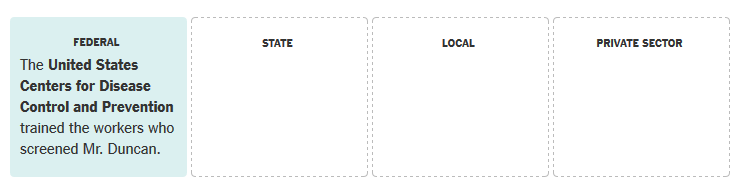

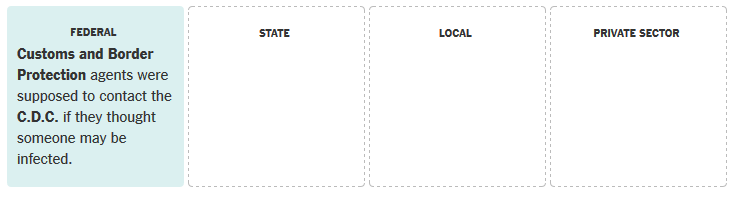

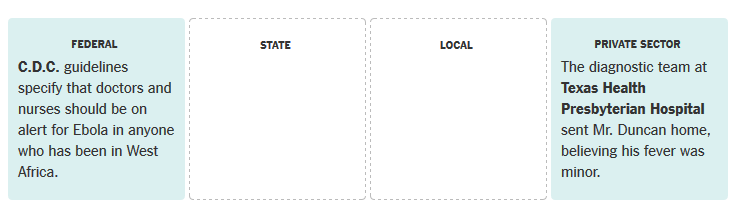

The handling of the first person found to have Ebola in the United States has raised questions over whether the country is prepared for an outbreak. At least a dozen federal, state and local government agencies, as well as several private entities, were involved in responding to the case in Dallas.

Foreign Airport Check-in

At the airport in Monrovia, Liberia, Thomas Eric Duncan is checked by health workers. His temperature is normal, and he answers “no” on a questionnaire about whether he has been exposed to anyone with Ebola in the past 21 days. Four days before his flight, Mr. Duncan helped a sick woman to the hospital and then back home, where she died a few hours later.

The screening process is not foolproof. Because it can take as long as 21 days for someone infected with Ebola to develop symptoms, a lack of fever does not necessarily indicate a lack of infection. Also, travelers may not realize they had been exposed to someone with Ebola, or they may not reveal it.

Going Through U.S. Customs

Mr. Duncan flies from Monrovia to Brussels, then to Washington and finally to Dallas. He clears customs in Washington, where he may have been given a flier on the warning signs of Ebola. American officials believe Mr. Duncan did not have a fever when he arrived in the United States.

On the day Mr. Duncan died, federal officials announced that passengers from the three countries most affected by the Ebola outbreak will be tested for fever by Customs and Border Protection staff members on arrival in the United States. Those who have a fever will be evaluated by a C.D.C. official. It will be up to local health departments to decide whether to place them in quarantine.

Health experts say the new measures are more likely to calm the public than to prevent Ebola from entering the country. They caution that a temperature check on arrival would almost certainly not have detected the virus in Mr. Duncan.

First Hospital Visit

Louise Troh, Mr. Duncan’s fiancée who he had gone to Dallas to visit, drives him to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. He has a mild fever and abdominal pain. He tells a nurse that he was recently in West Africa and that he had not been around anyone ill.

In allowing him to leave, the hospital delayed Mr. Duncan’s treatment and provided more opportunities for the infection to spread to others.

The hospital has offered multiple explanations for why Mr. Duncan was released. Officials initially said that Mr. Duncan’s condition did not warrant admission. On Oct. 2, the hospital released a statement blaming a flaw in its electronic records system for the decision to send Mr. Duncan home. The next day, the hospital said there was no flaw in the system and that Mr. Duncan’s “travel history was documented and available to the full care team.”

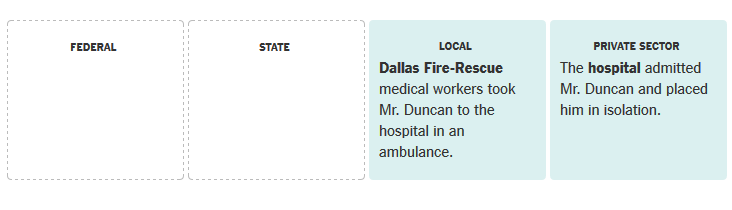

Second Hospital Visit

Mr. Duncan’s symptoms worsen, and Ms. Troh’s daughter calls 911. She warns the arriving emergency medical technicians that they need to be careful because Mr. Duncan is from “a viral country.”

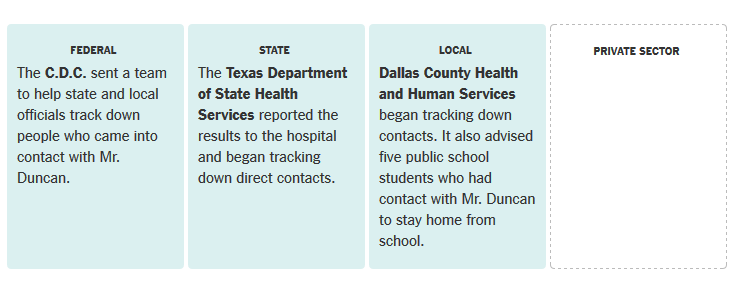

Testing and Contact Tracing

Based on Mr. Duncan’s symptoms and travel history, the C.D.C. recommends testing his blood for Ebola. Tests by the C.D.C. and a state lab come back positive for the virus.

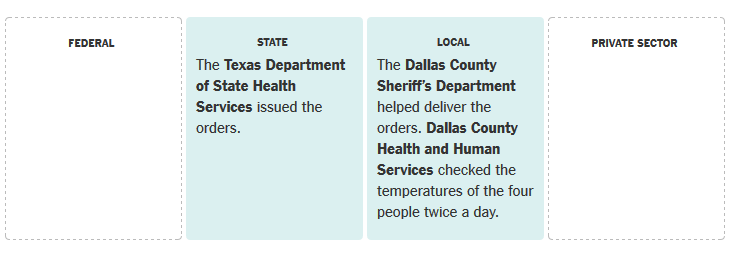

Isolating the Closest Contacts

The four people living in the apartment where Mr. Duncan was staying — Ms. Troh and three of her relatives — are ordered to remain there and not receive visitors until a 21-day monitoring period is over.

Sanitizing the Apartment

A company is hired to sanitize the apartment, but the workers cannot start because permits to transport the contaminated material are not in place.

The family was living in extremely unsanitary and potentially dangerous conditions for days after Mr. Duncan tested positive for Ebola, and for more than a week after he first visited the hospital with symptoms.

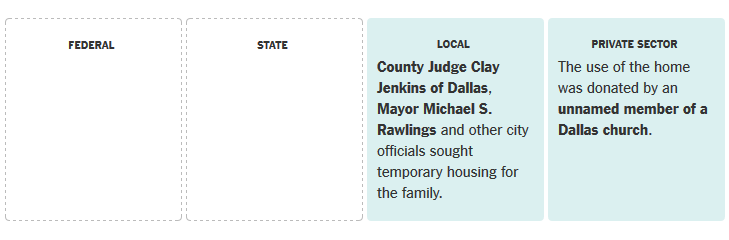

Moving to a Temporary Home

Ms. Troh and her three relatives move to a temporary home, where they remain under quarantine.

For several days before the donor came forward, local officials tried to place the family in hotels, apartment buildings and elsewhere, but they were unable to find anyone to take them in.

Sanitizing the Apartment

The Cleaning Guys begin decontaminating the apartment. An emergency permit is issued for an Illinois company to transport Ebola-contaminated items from the apartment and the hospital.

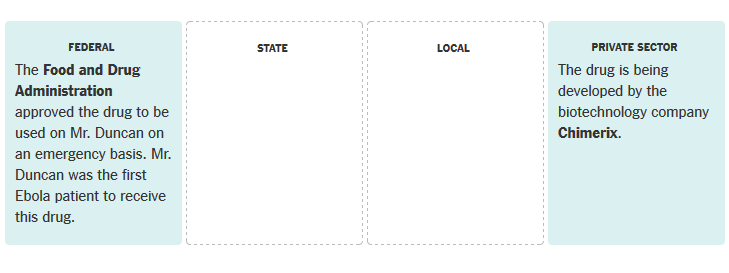

Trying an Experimental Drug

The hospital administers doses of an experimental drug called brincidofovir.

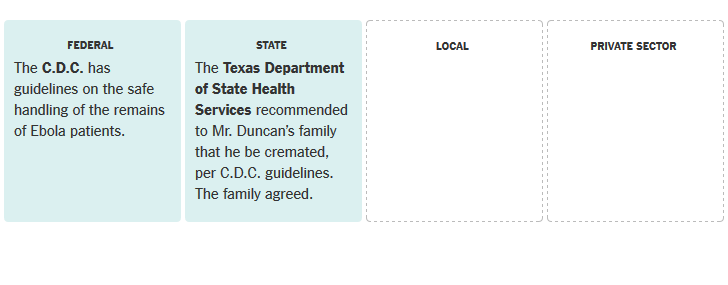

Handling the Body

Thirteen days after his first visit to the hospital, Mr. Duncan dies.

By KAREN YOURISH and LARRY BUCHANAN for NYT

———

Sources: James G. Hodge Jr., professor of public health law and ethics, Arizona State University; Leila Barraza, assistant professor, University of Arizona; United States Centers for Disease Control; Dallas County Health and Human Services; Texas Department of State Health Services; City of Dallas; Food and Drug Administration; United States Department of Transportation; United States Government Accountability Office; Dallas County Judge; Dallas Independent School District; Texas Health Resources