But Africa has not moved beyond a partial establishment of the principles of Maat in her pursuit of democracy, even some 70 years past colonial Occupation, and theories regarding the natural rights of the citizen (the family unit) still play a less significant role in African History than would in a society completely accepting of the principles of Maat, much like Ancient Africa.

However, the natural rights of the family (the Extended Family) and hence the Clan under the traditional constitutionality of monarchical Africa was the single most important vote, and in that regard the structure of African popular government asymptotically approached Maat in principle, in tradition and lacked only in achieving a more perfect democracy.

Needless to say that the Rights of Men and Women, as people, were never heard of, for slavery, the slavery of men and women of tribes conquered, or servants bought, but whose offspring became a natural addition to the family unit and often of equal standing within the family structure as their masters and madams, was an accepted practice in all African States.

Such development of popular or constitutional government alongside the monarchy as we see in Kemet, down through Asante and Dahomey, was in part due to the pressure of natural grievances but far more due to entrenching the tradition and principles of Maat than any theories regarding the nature of government and the claims of the people.

With the fall of Ghana, Mali, Songhai and later Asante and Dahomey by 1900, the rule of the family unit came to an end in West Africa. Some form of local self-government still based on the old tradition persisted for many generations in the towns and cities that rejected or have not been heavily influenced by Christian Missionaries and European Culture. But in an oligarchic form, it too, ultimately is dying out.

For nearly a century, from the days of the Asantehenes and the Ahosus of Dahomey till the fully Independent African States kicking out against European Occupation, there was never among any group of African States, civilized as they previously were, any more than there had been in Europe till the imperial power ceased at Rome in the fifth century, a serious attempt either to restore the struggle to achieving a more prefect state, free of colonial or imperial influence, or even to devise a regular constitutional method for choosing an autocratic head of the state tied to the customs and traditions of traditional African governance.

Few things in history are more remarkable than the total eclipse of all political thought and total abandonment of all efforts to improve political conditions in a highly educated and intelligent population such as were the inhabitants of the Western half of Africa till the establishment of more complex societies in 1500 B.C. and the emergence of Ghana in the eighth century.

The subjects of the Eastern half of Africa, Kemet, Kush and Nubia, at least some fifteen centuries prior to the movement of some of her people westward, were interested in letters and learning, in law and in medicine, in art and above all, after the rise of what is now called Vodun in West Africa, in religion. Africa owes most of her intellectual history to the accomplishments and prowess of key polymaths like Imhotep, Akhenaten and Ptahotep, to mention but a few.

In military accomplishments way before the Kandakes of Kush, Sundiata Keita of Mali, Hannibal of Carthage, and the Warriors of Benin and Dahomey, Narmer and Tahaka of Kemet occupied the single most important position among the pantheon of Warrior African gods, in the Book of Our Ancestors. These were undoubtedly the greatest generals of antiquity.

But though the political and historical literature of Ancient Africa had been preserved in Ghana, Mali and Songhai long after Nubia and Kemet had fallen to foreign invasion, nothing of a political kind was produced in the field of theory, and nothing of the political kind was attempted in the field of practice resembling of the principles of Maat. People were weary of politics. The principles of Maat in government had been tried, and had to all appearance failed to perpetually protect Ancient African States from invasion, plundering and occupation by foreigners.

Despotic monarchies everywhere dotted the Motherland. The few minds cared for other things, or perhaps despaired. The masses and the various families were indifferent, and would not have listened. When a rising occurred it was because people desired good government, not self-government. Who can say what has happened once may not happen again?

The progress of popular government in contemporary Africa from its obscure Kemetian beginnings 3000 B.C. may be referred to four causes:

The influence of religious ideas.

Discontent with royal or oligarchic misgovernment and consequent efforts at reform.

Social and political conditions favoring equality.

Abstract theory.

It would be impossible to sketch the operation of these causes in all contemporary states, so I confine myself to those few in which democracy has now gone furthest, treating each of these in the briefest way.

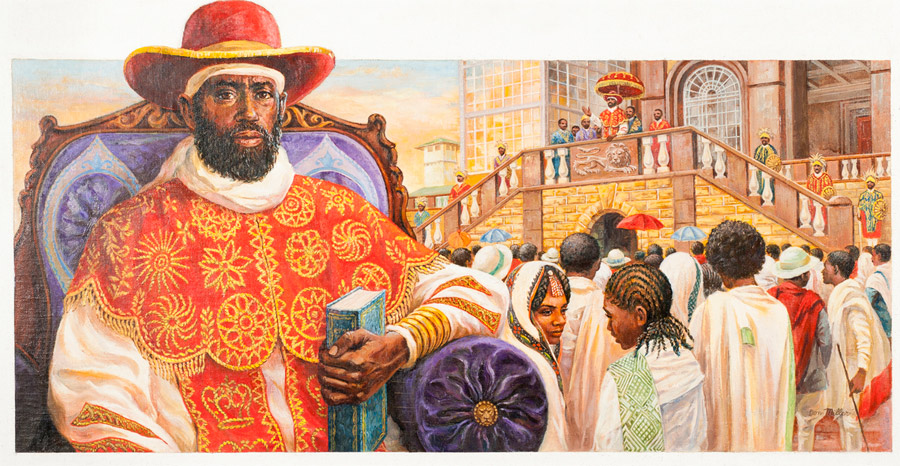

In Ghana there are three marked stages in the advance from the old monarchy, as it stood in the accession of the kings and chiefs, to popular government. The first is marked by the struggle, which began between the Asantes and subordinate ethnic groups such as the Fantes, and between Dahomey and her member states like the Agave and the Anlo, and ended with the defeat of the Asantes by the British in 1909, and the defeat of Dahomey in 1894.

This was a struggle primarily against ecclesiastical Vodun oppression – Dahomey was a champion for institutionalizing and standardizing her form of traditional African religion, while Asante, having been re-birthed out of an oracle by her Chief Priest, Komfo Anokye, who hailed from the cult township of Nokye in Dahomey, was equally consistent in entrenching her belief systems; secondarily against the civil misgovernment of the political institutions setup to manage the affairs of subordinate or members states, and in particular against the exercise of certain royal prerogatives deemed to infringe the civil liberty of the family unit, such as the claim of the Asantehene or Ahosu to levy taxes and issue executive ordinances, in addition to taxes and levies by local Chiefs, without the consent of the council of elders of the various clans and hence the heads of all family units.

The struggle, conducted in the name of the ancient rights of the family unit, occupied more than half a century, and brought about not merely a recognition of these rights, but also an extension of them sufficient to make the House of Parliament alongside the National House of Chiefs the predominant power in the new state of Ghana under Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah (1956 – 1966).

It was prompted by a spirit of resistance to actual oppressions, helped rather clandestinely by the British and the French – who had their colonial exploitative interests at hand in West Africa but had been contained by both Dahomey and Asante – rather than by any desire to assert the abstract right to self-government. Yet in the course of it, questions of a theoretical value did twice emerge.

To be continued…