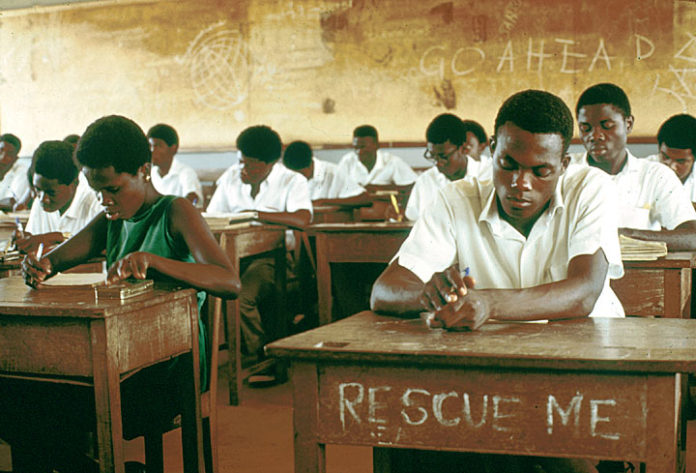

School as it is practiced now in its modern, colonial dimensions, with its instruction in colonial languages, with its denigration and scorn of local wisdom, with its worship of foreign texts and faraway heroes, does far more harm than good for our communities. Our schools’ attachment to colonial languages creates an environment where oral cultures thrive. Schools in colonial languages breed oral cultures by the hundreds, cultures that are unfortunately lacking in complexity of thought, analysis, and critical dialogue—despite what their staunch proponents might believe.

Oral storytelling, folklore, and dialogue is not detrimental in and of itself, so long as that mode of communication, the spoken word, is accompanied by the written word. This is not the case, however, as colonial schools stifle our written voices in exchange for privileging our spoken words.

During the time we should be learning to philosophize, write, think, and analyze using our local languages or at least using a language with a Bantu grammatical structure, schools literally silenced our brains and coerce us into abandoning all we have learned at home—only to start anew, from square one, with languages that are a long way from home, languages that sounds odd rolling off our tongues, languages which honestly we never master.

The result: hunger for schooling in another’s tongue leaves us perpetually illiterate. We seldom correspond in writing, besides a few words or sentences here and there. When is the last time you wrote an essay? And I do not mean an essay for school or for work or for monetary exchange, but an essay for no reason at all…just because.

That, writing for writing’s sake, is the mark of true, unbounded literacy. And that is precisely where the problem of colonial schooling, colonial language, and the perpetuation of oral culture lies. The colonial-school-mastered-student, the one who aced all the exams and collected all the degrees to boot, unfortunately, does not contribute to the public scholarly written archive. He only writes in school, for school. He has no sense of the signs of true literacy and education: his ability to write when no one is looking. His colonial school values no such practice. And thus we are left with a self-proclaimed highly-educated population that never writes.

The result of this conundrum: We seldom digest the local man’s manifesto. What has the local man written of his troubles, his triumphs, his truths?

What would our grandmothers have written about their lives and communities? One thing is certain: We will absolutely never know. Unless they have written it down.

Without a writing culture, we are also left with no possible way to determine who is knowledgeable and who is not. An oral culture privileges those who speak the loudest, or those who have the sweetest, deepest, or sexiest voices. More often that not, people speak off the cuff. Our written words are a product of greater reflection and care. We are held to a higher standing for what we write than for what we said. No writer can say, he did not mean something that way. But a speaker can always receive the benefit of the doubt for a poor choice of words. A society that does not write does not carefully examine any words and is, thus, prey for easy co-optation or manipulation.

Colonial schools cannot liberate our minds. They rather confine our freedoms. As we struggle to pen simple thoughts down in a foreign language, school belittles us, so that we no longer write down our thoughts. We rather defend our perpetual illiteracy and suggest our cultures are oral instead. We shall talk more and write less. Why though do we allow school to diminish our brains in this way?

Why are we not ashamed we do not have a box full of letters our grandmothers wrote to us when we were little so that we could read them now as adults? Why are we not ashamed we do not today write letters to our grandchildren, that we do not today keep boxes of written thoughts for our posterity? Why don’t we start writing those missing documents tomorrow? Why not now?

In essence, school should make us learned scholars, at least that is what we were told when we decided to abandon our village abodes and enroll in mission school. We should write more after our education, not less. Though this is obviously not the case. Why are we unwilling to admit schooling in foreign languages has failed us and stunted our growth? Why are we reluctant to change this regressive pattern?

We have to confront our collective miseducation. We have to confront our socially ingrained culture at its present, the modern oral culture. We are in such admiration for the rhythm of our own sounds, that we forget we have nothing to write in reply.

Our written silence, however, signals complicity with those who have written and who write profusely. Because if we do not write our stories only those stories that are written will have the chance to endure throughout time. How is it that we know so much about our ancestors, but through their written documents buried beneath the sands from time immemorial?

Even today, as happened hundreds of years prior to Africa’s pale ages, terrorists will attempt to destroy our writings—and will at times succeed. Though this is no reason to deter from the goal of full literacy in our local languages, first, and if one so desires, in other languages later.

The colonial mission school that exists tragically stunts our growth and development. Our understanding of local languages during childhood is stifled prematurely and never nurtured. Colonial languages are no incubator for our full literacy. Our best hope to regain communicative power—to read, write, think, analyze, and critique—is through using languages that make the most sense to us; languages that bridge gaps between the cities and the villages, the rich and the poor, the old and the young, the past and the present; languages that allow us to read the village man’s manifesto and invite us to explore his world through his writings.

The answer is right before us. Our collective literacy will be forever evasive if we refuse to put pen to paper in our local languages.

Another welcome challenge from Gbetohemaa Sister Nefetiti!

My initiatic master emphasized the point that “It is the writers who will change the world.” We have so much precedence for this salient truth as even our Kemetic Ancestors recognized a Ntrt specifically for her dominion over writing. She is called Seshat.

In this initiation writing and language is the cornerstone, particularly what we call Medu Myeet, as it has been preserved by the Dogon of the Goulmu extraction hailing from Burkina Faso. As such I couldn’t agree more. Language is the key and foundational component that is responsible for the transmission of culture and thereby identity. Since we have been inducted into the “scholarly” halls of our colonial miseducation where our “learned” elite have voraciously lapped up the slop of these mongrel languages as a badge of honor and where every day students aren’t afforded a way forward without showing proficiency in them, where has society and the cultural identity of the people gone? We now ride the coattails of the ones whose language we’ve learned.

People will forget what you said, people will even forget what you did, but people will never forget what you wrote. Thanks for sharing real wisdom sista Nefetiti.