On the campus of the University of Mississippi in the USA, a statue of the university’s first African American student, who enrolled in 1962 amid rioting that left two African Americans dead, stands a few hundred yards from a monument honoring Confederate soldiers – an army that unsuccessfully defended the inhumanity of the South’s economy that ploughed at the back of African slaves.

Ole Miss administrators call this a powerful symbol of progress. That it reminds them of the progress they have made since their involvement in the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade – the mechanization of black bodies for profit. They claim this peculiar arrangement symbolizes a reminder of ‘man’s inhumanity to man’ in the not so distant past.

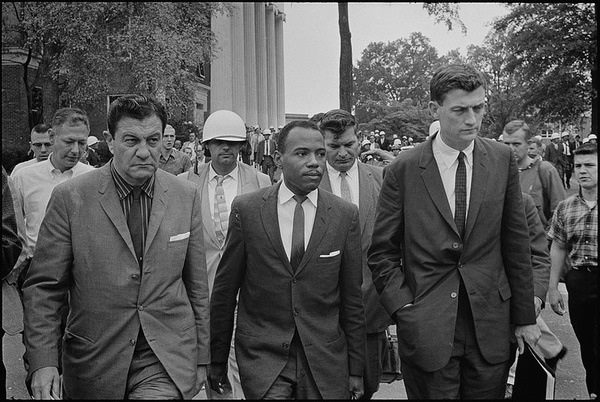

But when two unidentified men placed a noose around the bronze neck of James Meredith this week and left behind a flag with the Confederate battle emblem, it set into motion a new round of soul-searching in a place where past exploitation and present prejudices against African Americans still restlessly coexist.

“These events continue to happen semester after semester and year after year,” the student newspaper, The Daily Mississippian, said in an editorial. “All of our actions seem fruitless and impotent, leaving us broken, scared, humiliated and with burning, difficult questions: What do we do about it? How do we stop these events from transpiring?”

By many measures, the university, which hosted a presidential debate in 2008, is an entirely different place from the one Mr. Meredith entered. About 41 percent of its undergraduates are from outside Mississippi, up from 33 percent a decade ago. And though African Americans make up 15 percent of the student body, yet about 80 percent are university athletes, which brings the enrollment of African Americans for academic purposes alone to a stupefying 3 percent, compared to the over 75 percent white enrollment.

This is also a reminder of the university’s Jim Crow past that continues to permeate its idyllic slave master looking campus, set among oaks and magnolias and fabled for the Grove, and perhaps the reason for its hallowed football tailgating spot in a region full of only imitators.

An epithet-saturated demonstration in the aftermath of President Obama’s 2012 re-election resulted in the arrests of two students. More recently, a September production of “The Laramie Project,” a play about the 1998 murder of a gay college student in Wyoming, gained notoriety after an outbreak of homophobic heckling by audience members.

University officials readily acknowledge the residual intolerance that has so often called attention back to a place where the federal authorities had to force Mr. Meredith’s enrollment.

And even as administrators note a few successes, they concede that they are confronting a challenge with deep and difficult roots in thought and learned racism against African Americans.

“There are some people who see this institution through the eyes of the ‘60s and forever will,” said Donald R. Cole, the university’s assistant to the chancellor for multicultural affairs.

Professor Cole and other administrators, including Daniel W. Jones, the chancellor, contend that while Ole Miss has made considerable headway in its quest to make peace with its past, change can take hold only so quickly.

“The university has taken steps, both collectively and individually, to try to bring ourselves into the mainstream of America on thought about race,” Dr. Jones said. “If you look at how we behave and perform in most ways, we look more like other universities than we have in the past.

That being said, you can’t erase the reality that the integration of this university was done in a more violent way than at other universities in the country.”

But many students wonder whether the administration had exhausted its options and argue that the student body needs to mount a more aggressive stance against bigotry.

“If you bill yourself as Ole Miss and you call yourself the Rebels and the first thing a visitor to the campus sees is a Confederate monument, whether intentionally or not, it conveys an image,” said Charles W. Eagles, a history professor. “And that image is an image tied to the past, not a 21st-century image.”

Professor Eagles, who wrote what many here believe is the definitive account of the university’s integration, argued that the university must take more forceful action that could anger its supporters.

“If I could do one thing, the place would never be called Ole Miss again,” he said.

In a state, though, where the university’s decision to change its official mascot from Colonel Rebel prompted a bill in the state Legislature to overturn that action, those words come close to heresy. And some, seeing the recent incident as an example of isolated misconduct rather than substantial problems, fear the administration could overreact to it.

Mr. Meredith said the “nonsense” episode would intensify his effort to have his likeness removed from the university’s campus.

“It’s a false idol, and it’s an insult not only to God, it’s an insult to me,” Mr. Meredith said.

University officials said they had begun taking steps to consider changes to the campus — where the road encircling the basketball arena remains Confederate Drive — even before this week’s incident.

Dr. Jones said that Edward L. Ayers, the president of the University of Richmond, who worked in the Virginia capital to promote dialogue about the city’s own racial friction, would visit Oxford this weekend “to look at our campus, look at our names and offer us some advice.”

But Ms. Dunigan said changes were also needed on a smaller, more personalized scale, among individuals who might carry with them traditions that quietly cause pain.

“When we tailgate at the Grove, you still see people carrying their Confederate flag,” she said. “They say, ‘That’s my history. That’s my heritage.’ But do they know what that actually symbolizes? It’s still hurtful.”