Spike Lee has fallen off the map.

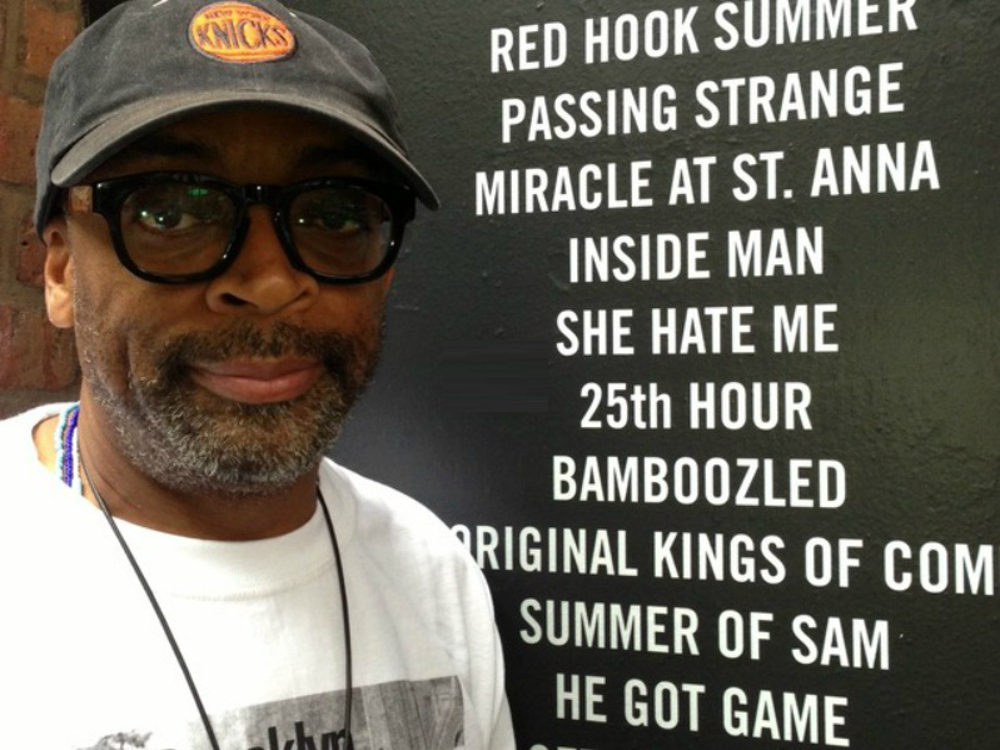

Decades ago, the award-winning director was once a beacon of independent filmmaking. His multiple classics, namely She’s Gotta Have It (1986), School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Mo’ Better Blues (1990), Jungle Fever (1991), Malcolm X (1992), He Got Game (1998) and Bamboozled (2002), all received some level of critical and/or commercial success.

Although Spike Lee’s earlier films were not without their technical flaws, they were vibrant with character and explored facets of American life yet to be witnessed on screen.

But since this wave of earlier films, Spike Lee has not brought forth any Black-oriented film that has been the subject of favorable discussion. Instead, we’re more likely to see Lee spectating from the front row of a New York Knicks game at Madison Square Garden than at a film screening discussing his latest remarkable masterpiece.

Since his golden era, Lee hasn’t produced any work that has had a resoundingly successful reception from critics. The past fifteen years have shown little progress for the director who started his career at a blistering pace with numerous films that not only tickled the racial and political consciousness of Americans but also illuminated directorial potential that some might argue has gone unrealized.

Spike Lee’s She Hate Me (2004) is most remembered for being forgettable.

His Oldboy (2013) remake was deemed unnecessary.

Red Hook Summer (2012) was said to lack focus–a common criticism of Spike Lee films. Critics also noted a rehashing of characters we’ve seen before in previous Spike Lee Joints—for example, drunken old men who are wise beyond their rambling boozed up selves and wandering kids in underserved neighborhoods. But these recurring character types appeared without much deeper insight into the current social conditions of the times.

The best one can say about Miracle at St. Anna (2008) is that the film had good intentions. Lee sought to fill a void in World War II dramas, and particularly in reaction to Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), in which African Americans’ contributions were uniformly invisible, though in real-life, Blacks played prominent roles in facilitating victory in battle. The execution fell short of intention. The movie had a laborious pace and its plot was largely disjointed.

Inside Man (2006) was no doubt a commercially successful film and proved that Lee could direct a viable Hollywood picture, though it is somewhat unusual for artistes of Lee’s status to venture along the route of helming studio pictures. Even with its commercial success, Lee’s core fans desired a return to the Spike Lee social problems joints that poked holes in a racially charged America, the very joints that have evaded our silver screens for years.

With Chiraq slated for a 2016 release, Spike Lee shows promising intentions of moving back to the film topics that were once his bread and butter in the 1980s and 1990s.

Backed by Amazon Studios, the film turns to Englewood, a neighborhood in Chicago that at one point had the second highest murder rates in the city. Local Chicago rapper King Louis coined the phrase Chiraq, which unites Chicago with Iraq in their overlapping crises of violence.

Controversy alone has driven debate over the film and its potential reception, a technique Spike Lee has successfully used previously to generate marketing and promotion without ushering out a dime.

Chiraq has drawn early opponents even before production has started.

Englewood is more than a war zone to its residents, who hope that Lee who in his indictment of Black-on-Black violence also will not shy away from capturing the structural problems–namely poverty, joblessness, and provocations by white institutions–that shape the material conditions in the neighborhood.

Although Chiraq’s premise, along with early reports of Common, Samuel L. Jackson, and Kanye West attached to the film, sounds as if it would successfully draw audiences to the theaters, the bigger question is whether Spike Lee still possesses the skilled touch that will make a poignant thought piece from a sizzlingly relevant social issue.

As an L.A. Laker, Kobe Bryant had his glory days. So did Chelsea’s Didier Drogba. But we can all agree that those days of spectacular plays are long in the shadows of both men. Now their contributions to their sports, basketball and soccer, respectively, are inputs from old men who fear to relinquish their connection to the world, although the brilliance of their star has faded.

These patterns seem to embody Spike Lee’s decline from the locus of Black filmmaking.

What astonishes most observers, however, is the recognition that filmmaking ought to be different. The craft is unlike professional sports where muscles tire and ailments undeniably emerge. A filmmakers’ blade should sharpen with age, not dull.

Has Spike Lee reached the end of this road when it comes to making eye-opening films about Black people and culture in America?

Some question whether he is culturally equipped to tell a Black story from the ‘hood anymore via the argument: Can we still expect these sorts of films to come from filmmakers who reside not in their local communities but in million dollar estates in Manhattan?

Surely people who do not live “in the ‘hood” can tell those stories with conviction; that is, if they conduct adequate research. But is it hard for Black filmmakers, especially those removed from Black communities in their daily interactions, to accept that they cannot rely heavily on their own experiences or personal memory and must do research to tell Black stories?

Sometimes its difficult for people to understand that when removed from the conditions in which their greatness emerged, it can be difficult to replicate the environment that honed their talent, and consequently, the talent wanes. Rappers face the same conundrum with their art. Their songs become less sociopolitical and “down” when interwoven with the comforts of affluence.

Chiraq might resurrect the career of a floundering filmmaker. But if it fails to do so, perhaps we should speak of Spike Lee in the same way as those who were once great on the court, but are no longer starters or reserves on the bench. His banner can hang in the arena as a symbol of what once was, but if Chiraq tanks with critics and audiences, we must perhaps regrettably pronounce that Spike Lee’s talents are now eligible for retirement benefits.