“A specter is haunting Europe, the specter of communism” declared Karl Marx in his work, the Communist Manifesto. Now in the early decades of the 21’st century, a specter is haunting the world, the specter of capital inequality. This is the basic premise of the new book by French economist Thomas Picketty aptly titled “Capital in the 21’st Century”.

This new book has created a veritable storm in economics, politics and public policy. We will examine the findings of the book and its conclusion from an African perspective.

He starts by posing the following fundamental questions; what do we know about the evolution of wealth over the long term? Do the dynamic of private capital accumulation lead to greater concentration of wealth in the hands of a few people as the German economist Karl Marx theorized in the 19’th century?

Or on the other hand, do the balancing forces of growth, competition and technological progress in the later stages of development lead to a reduction in inequality and greater harmony among the classes as was propounded by the American economist Simeon Kuznetz in the 20’th century?

What do we really know about how wealth and income has evolved historically and what key lessons can we derive from that knowledge for the 21’st century?

He employs an impressive array of data covering the 1700’s to 2010 that spans countries in Europe chiefly Britain, France and Germany, and Argentina, China and India for the rest of the world.

The data sets he works with are quite extensive for France and Britain as these countries have had an impressive data keeping structure going back hundreds of years involving estate taxes, measures of wealth and income tax records.

For China and India, the data is comparatively sparser than for countries in Europe. Having marshalled this impressive data universe he comes to the following fundamental observations are thus outlined.

Modern economic growth has tended to suppress the Marxian apocalypse of the collapse of capitalism but have not changed the deep structures of capital and inequality.

When the rate of return on capital exceeds to a large margin the rate of growth of output and income as it did in the 19’th century and as it is again doing now, then capitalism generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that undermines the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are built.

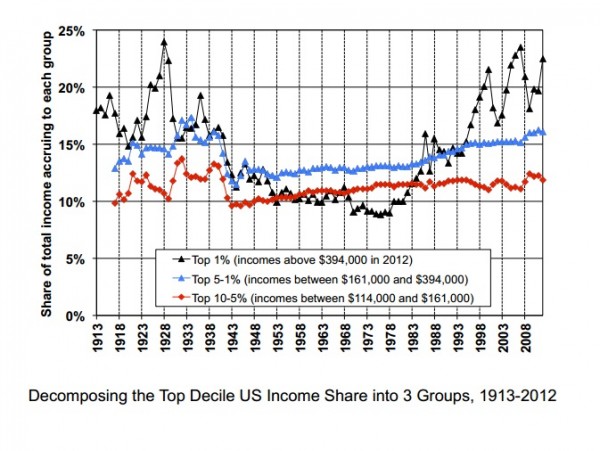

His analysis further shows that the capital share of national income that is industrial profits, land rents, building rents increased considerably in the first half of the 19’th century and stabilizes in the period of 1870 to 1914. It was a stabilization of inequality at extremely high levels.

Then in 1914, the great European Civil War also known as the First World War starts, it acts as an exogenous shock reducing the capital share of national income to about 30-35 percent by the end of the 1940s. Inequality stabilizes at this level from the 1950s until the 1970s. Then it begins to rise with the capital share of national income again rising in the 1980s through to the present.

We are now almost back to the extreme levels of inequality existing during the first phase of the industrial revolution. We all know what that led to, the communist revolutions and systemic shocks to the existing political order in the 20’th century.

He comes to two major conclusions;

“One should be wary of any economic determinism in regard to inequalities of wealth and income. The history of the distribution of wealth has always been deeply political, and it cannot be reduced to purely economic mechanisms. In particular, the reduction of inequality that took place in most developed countries between 1910 and 1950 was above all a consequence of war and of policies adopted to cope with the shocks of war.

Similarly, the resurgence of inequality after 1980 is due largely to the political shifts of the past several decades, especially in regard to taxation and finance. The history of inequality is shaped by the way economic, social, and political actors view what is just and what is not, as well as by the relative power of those actors and the collective choices that result. It is the joint product of all relevant actors combined.”

The second conclusion which is at the heart of the book is this;

“The dynamics of wealth distribution reveal powerful mechanisms pushing alternately toward convergence and divergence. Furthermore, there is no natural, spontaneous process to prevent destabilizing, inegalitarian forces from prevailing permanently…. Knowledge and skill diffusion is the key to overall productivity growth as well as the reduction of inequality both within and between countries.”

Hence we see in his conclusion the implicit assertion that the so called invisible hand of the market or so called perfect markets are incapable of righting the asymmetries of wealth and income inequality.

This calls for policy interventions from government and strong civil society stakeholders to provide the moral and ethical force field to reduce inequality and ensure a fairer distribution of wealth.

What are the implications and/or manifestations of this study in the African frame of reference?

He mentions a disproportionate level of capital as a share of national income in the 1700s and increasing rapidly in the 1800s. We can partially explain that by the massive theft of capital in Africa in that period by the western elite providing the deep financial reservoir for the western elite to increase their return on capital and hence contributing to the invariance in the structure of inequality in the west.

He does not address that in any detail as it is an uncomfortable fact that as a French economist, he cares not to remember. The imprisonment of the huge financial reserves of Francophone Africa in the financial system in France in the post-colonial period as their economies expanded, I daresay has contributed to the rising share of capital in national income seen post 1980s.

A huge part of the returns on their economic growth acts as a pumping station feeding the structural inequalities in France. The same can be said although to a lesser extent about Anglophone Africa.

Could the reduction in wealth and income inequality in the 1950s to the 1970s have been due to a deliberate policy intervention by the western elite as a reaction to fears of a victory by the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc?

Hence in order to keep their populations on their side in the ideological battles of the cold war, they reduced the levels of inequalities. But with the decline of the Soviet and socialist bloc in the 1980s and the seeming victory of the west, they reversed those policy interventions and returned to the status quo of extreme income inequality as there was no ideological counterweight to western economic thought and practice.

We can mention as a geopolitical projection of the structure of income inequality, Namibia. This is an African country that was forced to accept a constitution that land rights could not be challengeda in return for her independence from apartheid South Africa.

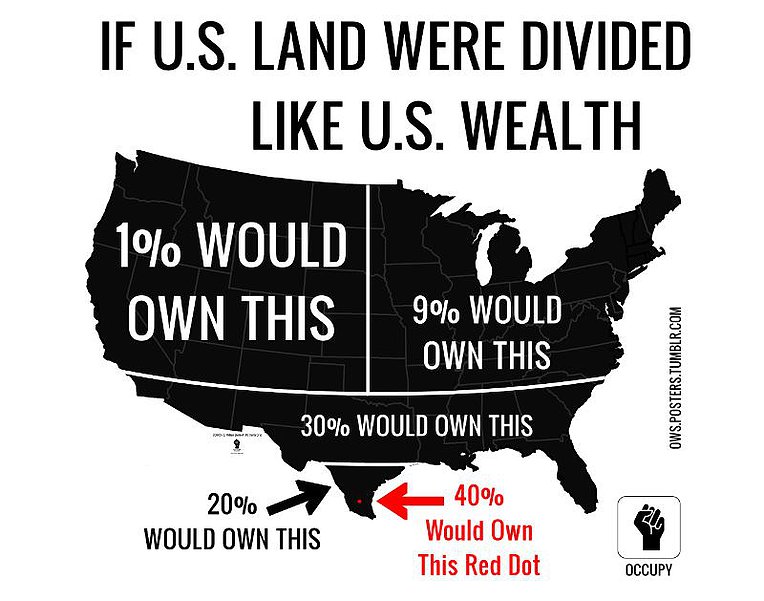

This has resulted in a situation where white Namibians making about 6% of the population own 90% of the land and out of this 90%, 40% is considered commercial property and is fenced off.

As Mr Piketty rightly points out, land as a form of capital can reap robust returns and can comprise a disproportionately large share of national income. How does his policy prescription of knowledge and skill diffusion address this imbalance in a country like Namibia?

In conclusion, we note that western economics is not a science; it is mired in its own internal contradiction that has resulted in extreme wealth and income inequality.

Africa must quit the intellectual laziness and find an alternative to western economics. We recall that in the economies of precolonial Africa, extreme wealth and income inequality was not known. This should be continue to be our frame of reference.

“The history of the distribution of wealth has always been deeply political, and it cannot be reduced to purely economic mechanisms”.

This brings us to our final point. If the West wants us to believe they are committed to eliminating the wealth and income inequality between Africa and the West then it requires a political process as well, not fancy economy theories and a laissez–faire market economy.

The ‘free market’, Piketty has shown with extensive data, only accumulates wealth in the hands of a few. It has no basis in reality and works against the well-being of the majority.

Or as our African economic elders had always believed it, ‘this thing [capitalism] will kill us, one by one, until one day any one who seeks a decent living without an inheritance will become like him who carries water in a sieve’.

This is a pointed analysis on Piketty and the African context. I wonder how many African heads of state are reading this or should be reading this article and the book.

Obviously people like you are reading and keeping up with the literature cos thats the only way one can get to the bottom of this heinous essence of western capitalism and imperialism.

Whatever Pinketty’s personal desires might be, I think a lot of people have latched on to his book because what they would like to see is R eliminated and if that also eliminates G, then that is all for the good as they envision a world where people live in some sort of genteel poverty (with a handful of mandarins (err, I mean civil servants) living slightly better). Also, it is very much within the possibilities of governments to readily reduce R (though certainly owners of capital can try funneling it to another jurisdiction), while it is more difficult to promote G, requiring, as it does, capital whose owners seek an R.

It was the Piketty-Saez graph of gross income inequality and the obscene 1% incomes that helped fuel the Occupy movement in 2011 in the USA.

With luck, Piketty’s magnum opus will push society over the Occupy edge and into a long overdue economic revolution and shakedown of the 0.1%.

Some excerpts from a recent Piketty interview:

“When inequality gets to an extreme, it is completely useless for growth. You had extreme inequality in the 19th century, and growth was not particularly large.”

–In other words, trickle-down poverty (i.e., Reaganomics) is useless for all but oligarchs and feudal overlords)

“It’s important to realize that innovation and growth in itself are not sufficient to moderate inequality of wealth.”

— In other words, taxing the rich – particularly the obscenely rich – is good medicine for a stable society.

“I don’t think there is any serious evidence that we need to be paying people (CEOs) more than 100 times the average wage in order to get high-performing managers.”

— In other words, CEO pay is a greedy, megalomaniacal farce).

“Education is the most powerful equalizing force in the long run to inequality and immobility. But it’s not enough. You need both education and taxation.”

— Note religious Republican Party support for the exact opposite solution: no education and no taxation.

Piketty presents hundreds of years worth of incontrovertible economic and greed daTa and history.

The exposition of the US and the EU as oligarchic greed can be very upsetting to the West.

The more that people look at the details of Piketty’s arguments there more holes there seem to be in them. And there’s one that I’ve not seen mentioned elsewhere as yet, which concerns his idea of a wealth tax as a solution to r > g. It seems, on closer examination, to be an entirely counter-productive idea.

One possible response to this is, well, what’s wrong with wealth inequality? Which isn’t what certain people want to hear these days so Piketty’s solution is that we should have a decent tax on wealth, thus reducing that wealth inequality. However, this runs into a problem which is the deadweight costs of the different forms of taxation.

Any tax levied, on whatever at all rates, means that there’s some economic activity that doesn’t happen just because we’ve levied the tax. That’s what deadweight means in this instance. From the work of Sir James Mirrlees we’ve also got a good idea of which taxes have higher deadweight costs than others. Repeated property taxes have the lowest such costs and that’s why land value taxation is such a good idea. Then comes consumption taxes (sales taxes and VAT), then income taxes and then, at the highest cost in lost economic activity for the revenue raised comes capital taxation. Wealth taxation is of course an extreme form of capital taxation (the less extreme version would be the taxation of returns to capital rather than the capital itself).

Given that we know all this, and Sir James does have a Nobel awarded for his study of optimal taxation systems and thus his views do carry some weight, there’s a problem with Piketty’s plan. Which is that deadweight costs are exactly the same thing as a reduction in g in his equation. So now think through what he’s proposing. Our problem is that r > g. Therefore we must do something. But what we’re going to do is the one thing which we know is most destructive of growth in g.

My friend, life is more complicated that it seems.

Piketty has written a 700 pg. tome, with extensive theoretical insights and ground-breaking empirical analysis, which Jehuti tries to capture in some three pages with very good success.

Do we not think it’s a wee bit intellectually dishonest or even arrogant to submit some 150 word comment on this post and think you have or can inform people about Piketty’s views on the effect on “g”.

Have you read the book? It seems most critical commentators are providing these pithy comments.

Perhaps your salary is dependent on ingratiating the rich), and Picketty’s 700 page tour de force of research and analysis can be deconstructed with a 150 word retort, deliberately leaving out say, in this case, all the variables that wealth redistribution could have on “g”.

That wealth tax doesn’t disappear into a black hole, it is transferred to people like my sister with 3 kids, a deadbeat ex and no affordable child-care. That’s a good thing for humanity… bad thing for your clients I guess.